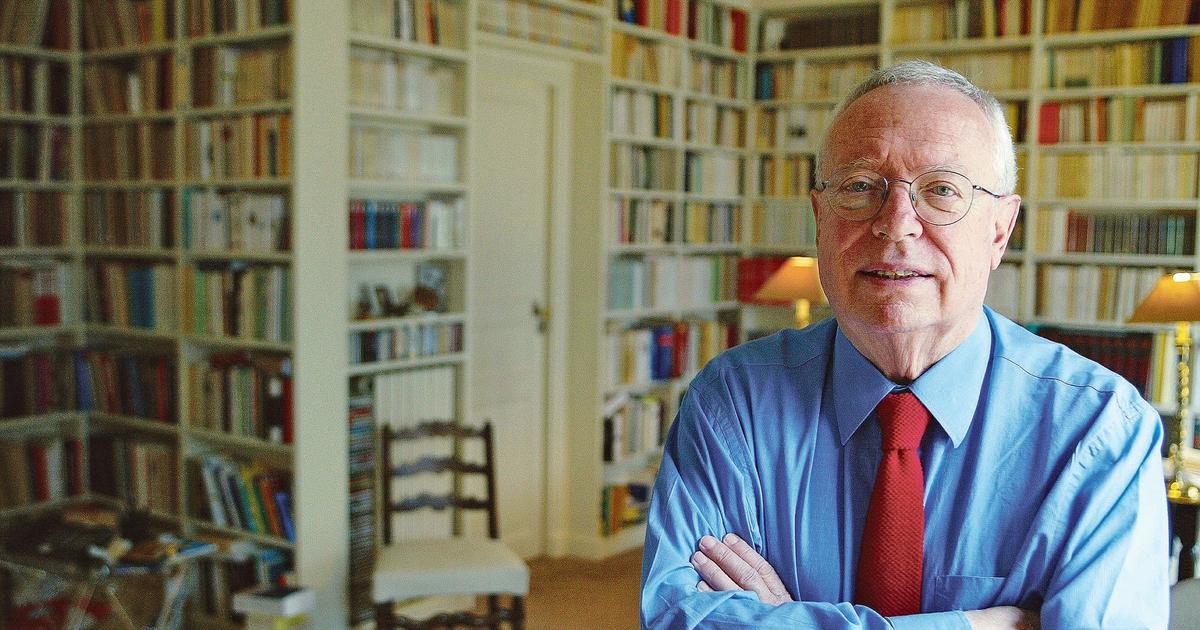

DISAPPEARANCE – The historian died on Sunday at the age of 91. Portrait of a disciple of Raymond Aron who built a considerable and unclassifiable body of work.

“II was born rue Guynemer, at the corner of rue de Vaugirard, in front of the Luxembourg garden, on the first floor, in the evening. My mother was expecting me for a little later.When he evoked his birth and his childhood, we found in Alain Besançon the attention to detail, the truth, and the talent for writing that characterized him. Born in 1932 into a family of the Parisian bourgeoisie, son and grandson of doctors, he established himself as one of the great French historians of communism and Russia before devoting major works to Christianity and the history of art. His intellectual itinerary has been that of a man whose life and work mutually nourished each other, that of a historian inhabited by his subjects of study, that finally of a great scholar who knew how to keep his distance from the logics institutions of the university.

As a student, he joined the French Communist Party in 1951, at a time when other young historians were meeting in his intellectual circles: Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, Annie Kriegel, François Furet. Like them, he returned his card in 1956 after the invasion of Hungary by the Soviet Union and the denunciation of Stalin’s crimes by Khrushchev. His convictions are shaken, his beliefs betrayed, and the feeling of having been manipulated does not leave him.

Read alsoAlain Besançon: “In the midst of the metaphysical void a vague humanitarian religiosity prospers”

The following year, in 1957, he passed the aggregation in history. If he goes to teach in secondary school – in Montpellier, in Tunis, then in Neuilly -, his deep vocation is to seek, to understand reality. “By training and mindset, I am a historian. Faced with the real, I ask myself: “How did such an event come into existence? What meaning should be given to it among the others?”“, he said. The first question he must shed light on is an intimate one: how could he, himself, have been seduced by communism? Ashamed of his past commitments, he wrote in his autobiography: “All this time I spent on Russian history and Soviet communism, studying and analyzing it, I hope it will be counted to me as penance.»

His forgiveness, many would say he got. The contribution of his writings to the understanding of communist ideology and the history of Soviet Russia is considerable. This also because his questions start precisely from a lived experience, explains the philosopher Philippe Raynaud: that of a former communist who went to Russia during his thesis, and who was viscerally struggling with this ideology. We owe him in particular a masterful investigation, The Intellectual Origins of Leninism, from his doctoral work. He explains how Marxist-Leninist ideology presents itself as a total explanation of the world, how the revolutionary momentum it conveyed was able to convince minds like him, and finally how important the religious matrix was to understanding this thought, which entrusted to the regime the care of watching over the salvation of souls.

When he began his first research work, attached to the CNRS from 1960, Alain Besançon met Raymond Aron. He became an assiduous listener to his seminar, where he notably met Jean-Claude Casanova and Annie Kriegel. They will participate together in the creation of Comment, “at his place, rue de Bourgogne“recalls his friend Jean-Claude Casanova. It will impose itself as the flagship journal of liberal thought, and Besançon will remain an active member until the end.

The figure of Aron is major in his intellectual trajectory: he considers him as his master and will follow in his footsteps by becoming one of the great thinkers of totalitarianism. All his life, he worked as a historian on the phenomenon that the philosopher had helped to circumscribe. And, like him, Besançon engages in the debates of his time; in 1979 he notably signed the declaration denouncing the denial of Robert Faurisson alongside Léon Poliakov and Pierre Vidal-Naquet.

After leaving the Communist Party, Alain Besançon joined the liberal thinking family. “He went directly to the side of the right”, says his friend Jean-Pierre Le Goff. And that, “he has not been forgiven in certain intellectual circles”. While François Furet had also left the PCF while writing in The New Obs to stay in the lap of the left, Besançon made a big difference; you can read it in The Express and in the “Debates” pages of the Figaro. However, the historian was anything but cataloguable, insists Jean-Pierre Le Goff. If many wanted to see him as a “reaction”, he was in reality a liberal and anti-totalitarian centrist in the purest Aronian tradition.

Historian of Christianity

Religion also occupied a central place in his life. A man of faith and a researcher anxious to shed light on the questions that inhabited him in the depths of his being, Alain Besançon has become a historian of Christianity. “Man quite independent of academic constraints and institutional logics”, he did not hesitate to dig a new furrow, testifies Philippe Raynaud. In his works on Soviet communism, he already insisted on the importance of religious sensitivity and intelligence to understand this ideology.

Read alsoAlain Besançon: “Catholics and Muslims, the same humanity, not the same religion”

He then approaches the subject of religion frontally in books like Three Temptations in the Church (1996), where he analyzes the attitude of the Catholic Church towards liberal democracy and Islam. Reject democracy head-on just like “to sink into it completely” are dead ends for the institution, he writes. A great admirer of Benedict XVI for his work as a theologian, he criticized the orientations taken by Pope Francis, corresponding for him to the “temptations” which the Church must resist. Sentimentalism should not prevail over the intelligence of faith; the Church does not fall into a “humanitarian religion”, he defended. Contrary to a modern spirituality adapting to the spirit of the times, Alain Besançon believed in the intellectual requirements of theology. He was also convinced of the importance of this field of knowledge for orientation in contemporary debates.

Because he was also an immense scientist, whom his friend Philippe Raynaud describes as a man with “very dense, very personal thought, founded on an original combination of a great historical culture, an interest in philosophy and a thorough formation in theology”. An intellectual who gladly freed himself from academic boundaries and who cut his teeth in psychoanalysis before turning his back on this discipline. It was not, in his eyes, the most relevant to grasp reality. Elected in 1996 to the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences, he sat in the Moral and Sociology section at first before joining the Philosophy section in 1999.

passion for truth

His friends remain marked by his immense culture, his great erudition and his insatiable curiosity. He read newspapers in Italian, taught in the United States – at Columbia, Princeton, Stanford -, and at the same time he maintained ties with many dissidents from Eastern Europe, in Poland in particular. His reputation went far beyond the borders of France.

Above all, until the end, he remained a man of fundamentally independent thought, “a free spirit like I haven’t met many“says Jean-Pierre Le Goff. A following historian as only compass his passion for the truth, and a man who held high the value of friendship.

stopwatch

April 25, 1932

Birth in Paris

1951-1956

Member of the French Communist Party

1957

History Aggregation.

1977

Publication of the Intellectual Origins of Leninism (Calmann-Lévy)

From 1977

Director of Studies at EHESS.

1996

Publication of Three Temptations in the Church (Calmann-Lévy)

1996

Election to the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences

2018

Publication of Contagions (Les Belles Lettres), bringing together ten of his main works

July 9, 2023

Death in Paris

Death of historian Alain Besançon, figure of anti-totalitarianism