Dr. Rick Sheff was culturally raised Jewish, but essentially an atheist. At Easter, his family would sit down to discuss possible scientific explanations for the crossing of the Red Sea during the Exodus.

“I’m sure Moses knew the tide charts,” his father joked. For them, it was an occasion to remember a political victory led by the historical figure Moses. It wasn’t about God. He learned at a young age that science held the answers to how the world works.

As a physician, Sheff shared experiences with his patients that seemed to defy current medical knowledge. One by one, he was able to dismiss each one as a rare occurrence, an anomaly. But this “data,” as he calls it, began to add up.

Two salient facts, experiences of telepathy, created cracks in his armor of atheistic certainty and disrupted what he calls his modern science-based “belief web.” Rebuilding that web required weaving together spirituality and a new scientific paradigm.

What is your “belief web”?

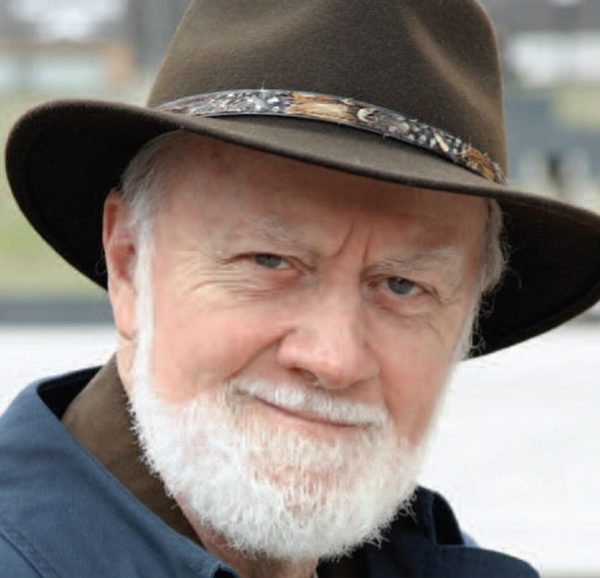

Sheff is a family physician, author, and medical director of The Greeley Company health consultancy. He studied philosophy at the University of Oxford before attending the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

As a philosophy student, he met the famous American philosopher Willard Van Orman Quine (1908-2000), who coined the term “belief web.”

Sheff summed it up this way: “Each of us functions in a personal web of belief. Think of it as a network of mutually reinforcing knowledge claims about the world.

“When we come across a fact, an experience or a scientific result, that does not fit into our network of beliefs, we have three options,” he said. The first option is to deny that they are “data”.

We can dismiss it as “mere coincidence” or, in a scientific study, assume that it is a measurement error. Scientists might say, for example, “Until that study is independently replicated by other people, I’m not going to accept that data as valid. It’s not data.”

The second option is to accept it as an abnormal data. It stays on the periphery of the belief network and does not influence the core. We might say, “It’s weird” or “It’s really unusual” and not think much more about it.

The third option is to allow it to settle deeper and deeper into the belief network, causing changes to the core. This is what finally happened to Sheff.

The data ended up breaking his web of beliefs. The breakup was painful at first, but “the result has been more joy than I ever thought possible.” That is the origin of the title of his book, “Joyfully Shattered”, in which he tells his story and talks about what he sees for the future of science: a science reconciled with spirituality instead of opposed to it. .

Telepathic experiences

Sheff had a patient, a 6-month-old baby named Ryan, who was terminally ill. The disease came on suddenly, and the baby’s father, Tom, understandably had a hard time accepting that his baby was going to die. Ryan lasted longer than expected, but he was very bad.

An unprecedented sense of insight washed over Sheff.

He felt that Ryan might be holding on because he knew his father wouldn’t be able to accept his death. Never had Sheff conceived such a thought or said anything like what she said to Tom: She suggested that he go to Ryan’s bedside and tell him that it was all right if he left. The baby died two hours later.

“The scientist in me wanted to say this was all a coincidence,” Sheff wrote in his book. “Labeling it a coincidence would preserve my faith in the science I had been trained in.”

Sheff’s wife, Marsha, was pregnant. His best friend, Susan, was also pregnant.

One morning at 4:30, Marsha woke up from a deep sleep and said, “Susan is in labor, I know.” She felt a tingling, an energy running through her entire body. She was sure of it, but she didn’t contact Susan and went back to sleep. She later learned that Susan had started having contractions at 4:30 in the morning.

“Suddenly I knew that people could communicate over a distance,” says Sheff. He recounted the experience to a medical colleague. The doctor replied: “It’s not data, it’s just a coincidence.”

In his book, Sheff describes his reaction: “What do you mean by coincidence? The statistical chances of Marsha waking up at precisely the same moment Susan woke up with her first contraction and of Marsha being flooded with energy and knowing that Susan was in labor at that moment are so slim that something had to cause it.

“Calling this mere coincidence is an outrageous leap of faith. It’s not good science.”

He told the Epoch Times that if someone had come to him with a similar story when he was still steeped in outright materialism, he would have gotten the same response. Sheff doesn’t resent people like this doctor friend; he understands his perspective.

He quoted Saint Ignatius of Loyola: “For those who believe, no proof is necessary. For those who do not believe, no proof is enough.”

“Must it always be like this?” Sheff asked.

the new paradigm

“Look, Rick,” Sheff’s doctor friend said when Sheff later spoke of a paradigm shift in science, “I have no doubt that he has had the subjective experiences that he has shared with us over the years. But they are just that, subjective. That is not science. Science requires data, public data that others can test, replicate, and disprove. Whatever you’re doing, please don’t confuse it with science.”

He was right, Sheff needed more. “A good scientist follows the data wherever it leads, instead of truncating that search based on preconceived notions or theories. He had had the courage to pursue those data that had led me to join the growing group of seekers of the new scientific paradigm. But he was right. My data points didn’t stand up to the test of science done right.”

Exactly one week later, Sheff met Dr. William Tiller, and in his work he found what he believes could be the basis of the new paradigm.

Tiller has had a successful career in the world of mainstream science. He is an emeritus professor at Stanford University and former head of the department of materials science and engineering at Stanford University, with numerous papers published in specialized journals.

But, like Sheff, he believes that science needs a paradigm shift on a Copernican scale. Dr Tiller told the Epoch Times in an interview in 2014: “There are thousands of people in the last 150 years who have done things so remarkable that they are put in the category of parapsychology, which orthodox science has wanted to sweep under the rug, because the results are not internally consistent with their results.

“Anything that doesn’t fit their type of results and the methodology to obtain them, seems like garbage to them,” he said.

One of Tiller’s main ideas that fascinated Sheff is that scientists can influence the results of their experiments with their own intentions.

Tiller’s experiments have suggested that human intent can change the pH levels of water, the activity of an enzyme in a test tube, and biological processes in a living organism. She has performed a series of experiments that demonstrate the physical impact that human intent can have.

Sheff wrote in his book on Tiller’s insight: “Since the days of Descartes, Bacon, and Newton, research in the physical sciences has rested on an unstated assumption that no human quality of consciousness, intention, emotion, mind, or spirit can significantly influence a well-designed objective experiment in physical reality.”

This is “a core assumption of a widely shared web of belief, but not a proven ‘fact,'” he wrote.

Lessons for the future in the history of science

By the end of the 19th century, many scientists thought all the important discoveries had already been made, Sheff said. They understood electromagnetism and thermodynamics, they had formulated the periodic table, Isaac Newton had established a paradigm for physics.

But at that time there were data that did not fit. The aberrations of Mercury’s orbit could not be explained by Newtonian physics, for example. Albert Einstein he hypothesized that the speed of light is not constant in general, but it is constant from any reference frame, which was a change from the Newtonian conception.

Einstein’s theories of relativity initiated another paradigm shift and showed us that space and time are not what we thought. Quantum mechanics brought about another change, and the current paradigm includes quantum mechanics and general relativity.

“But does anyone think that’s the end point, the ultimate paradigm, really?” Sheff asked.

Join our Telegram channel to receive the latest news instantly by clicking here.

© The Epoch Times in Spanish. All rights reserved. Reproduction prohibited without express permission.

How can you help us keep you informed?

Why do we need your help to fund our news coverage in the United States and around the world? Because we are an independent news organization, free from the influence of any government, corporation or political party. From the day we started, we have faced pressure to silence ourselves, especially from the Chinese Communist Party. But we will not bow down. We depend on your generous contribution to continue practicing traditional journalism. Together, we can continue to spread the truth.

Atheist doctor witnesses telepathy and now intends to merge science and spirituality