Diletta Guidi has just received the prize for the first book of the Chair of Studies on Religious Facts 2022, awarded by CERI-SciencesPo Paris for her book, ‘L’islam des musées. The staging of Islam in French cultural policies’. We publish here his interview granted this summer on the occasion of our double issue.

LCDL: More than 300 public museums house collections of Islamic art around the world. How to explain this enthusiasm born at the beginning of the millennium?

Diletta Guidi: Islamic art collections obviously predate the 2000s. This passion dates back to the 19th century, but around twenty years ago these objects began to be valued. Renovations have taken place in particular in Cairo, Berlin and New York and museums have been inaugurated. The Islamic Arts Department of Louvre already had the largest and most varied collection in the world. From the 2000s, on the initiative of President Jacques Chirac, it was literally taken out of the cellars.

The timing was not insignificant, this turning point began the day after the September 11 attacks. This enthusiasm responded to a political and educational need. Museums found themselves forced, by their hierarchy or by the context, to assume an unusual role to respond to an injunction for which they were not prepared. In the Middle East too, new places are opening up, notably in Doha in Qatar where there is a desire to show the West, through art, the image of an Islam of enlightenment, refined and peaceful.

In the case of the Louvre, what is the intention?

With the non-Muslim majority, we want to prove that Islam is compatible with the Republic. We promote a positive image, conducive to living together while preserving the works from the ups and downs of current events. This protection is a will of the experts but the objects of Islamic art are nolens volens associated with the news. To the Muslim minority, we want to give some recognition by installing these collections in the most visited museum in the world. The Islamophobic climate has pushed museum managers to produce an alternative discourse.

This presence within the Louvre testifies to a desire on the part of the State to further integrate the Muslim community into the history of the Republic. France, now multicultural and globalized – Islam is the second religion and the country maintains close relations with Muslim states – must produce a discourse on Islamic otherness. The country must provide proof of “compatibility” to its non-Muslim majority, recognize its Muslim minority, and project an Islamic-friendly image to Arab-Muslim partners.

Does the audience respond?

In this department, we do not rush as in front of the Mona Lisa. The visitor is always quite surprised by the presence of Islam. We come across several categories of public: experts and great amateurs of Islamic art, those who have lost their way in the meanders of the Louvre and people identified as Muslims who are looking for themselves in this category of art history.

Do they meet there?

The French Muslim community wants to identify with it and be part of this history, but it does not identify completely for various reasons, including the absence of objects from the territories (Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa) whose visitors are originating. French and foreign Muslims are confronted with another “silence”, that of religion.

We are in a national museum, respect for strict secularism remains a priority, hence the eviction of religious aspects in the course. So this desire is not fulfilled. No more than that of the State to show a refined and peaceful Islam, an Islam of the past which in reality does not exist.

The universalist assimilationist model put in place by the Louvre finds its limits. Hesitant about the links between art and current affairs, he wants to integrate and therefore assimilate this community by erasing what makes it special, that is to say its religious memory, its practice. The fantasies with which the visitor arrives are replaced by others.

Conversely, the Arab World Institute has a more flexible conception of the concept of secularism, especially since Jack Lang took over. As part of an intercultural and inclusive approach, the exhibitions recognize religious plurality and religious aspects. We put forward spirituality, Sufism, moderate piety while avoiding evoking radicalism.

Besides religiosity, are there other questions that the Louvre ignores?

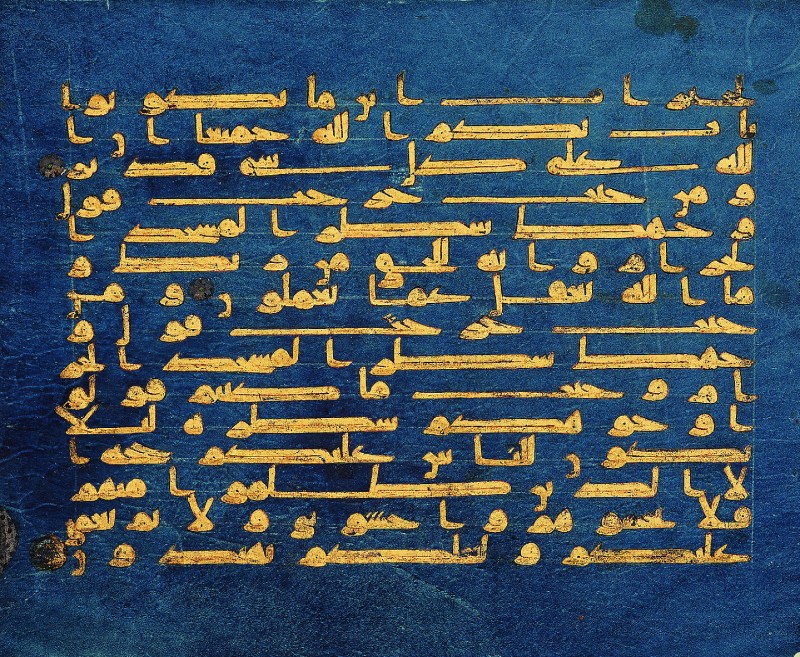

The current staging would benefit from making room for the complexity of Islam and the subjects that annoy. One could start by saying that the category of Islamic art was invented by the West in the 19th century and is contested today. The Louvre should explain to the visitor its choice to compartmentalize religion and, when it presents Koranic manuscripts at the end of the journey, to evoke the content and not to focus solely on the aesthetic aspect.

On the other hand, the colonial question is eluded. Nothing is said about the context in which these objects arrived in France, but the history of these pieces is also that of colonization. We go so far as to Frenchify the names of some of them. We speak of the “Mona Lisa of Islam” to designate an ivory pyxis or of the “Turkish Versailles” to describe a set of Ottoman ceramics. During the colonial exhibitions, works of Islamic art were already shown. A post-colonial rereading work remains to be done

Precisely will we observe, as for African art, requests for restitution?

There is no strong claim of belonging because Islamic art is a vague notion. This genre does not belong to a country. There are several Islams, so not a single built community can claim works, as in African countries where mobilization is powerful. Refund requests are rare. Iran or Turkey have made this type of request but none have succeeded.

This being the case, the current curator Yannick Lintz wonders about the biography of the works. It wishes to give a different impetus and integrate Muslim actors as is done in other international museums. Extraordinary progress has already been made and, in an institution rooted in its habits like the Louvre, this is not nothing.

Regarding what is being done elsewhere, how do you view the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, the only one in North America entirely dedicated to Islamic art?

Part of the Louvre team participated in the design of the Toronto museum display. The route includes magnificent works respecting the canonical chronology. Interestingly, there are temporary exhibitions and a host of side events involving the local Muslim community. Religion is not passed over in silence. Contemporary art is not excluded. The Aga Khan has done an excellent job taking into account the history of Islamic art while integrating contemporary creation. It is, in my opinion, exemplary.

“The Islamophobic climate has pushed museums to produce an alternative discourse”