Returning to Mount Lebanon in 1493, after 22 years spent in Italy, Gabriel Barcleius devoted himself to the reconstruction of his society through culture and poetry, and of his Church through Roman dogma and spirituality. This Maronite Franciscan sometimes exalts his people without failing to rebuke them. It is in his “Eloge du Mont-Liban”, that he both glorifies and castigates him in an attempt to remedy his exasperating ignorance.

Medieval Syriac literature came to an end in Lebanon with the Maphrian Gregory Bar Hebraeus (died in 1286), only to reappear timidly at the end of the 15th century with Bishop Gabriel Barcleius (1447-1516). The latter marks the beginnings of a Latinization of the Maronites, which was to lead to the founding in 1584 of the Maronite College in Rome, at the origin of the blossoming of the Lebanese renaissance.

Gregoire Bar Hebraeus

The Jacobite Syriac author Gregory Bar Hebraeus (1226-1286) was a physician and historian who had studied medicine at the school of Tripoli in Lebanon. He also studied theology, philosophy and quadrivium sciences including arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy. It was he who, in his chronicles, taught us that in his time, the inhabitants of Mount Lebanon had a particular Syriac language which pronounces the “Qof like a Phew“, a characteristic that we still observe today.

The death of Bar Hebraeus in 1286, in Upper Mesopotamia, coincided with the Mamluk invasions and the fall of the Latin county of Tripoli. The withdrawal of the Franks and the devastation of Mount Lebanon had no longer permitted literary productions for a long period of two centuries. It was not until the 1480s that another Syriac author, Maronite this time, Gabriel Barcleius, prepared to take up the torch.

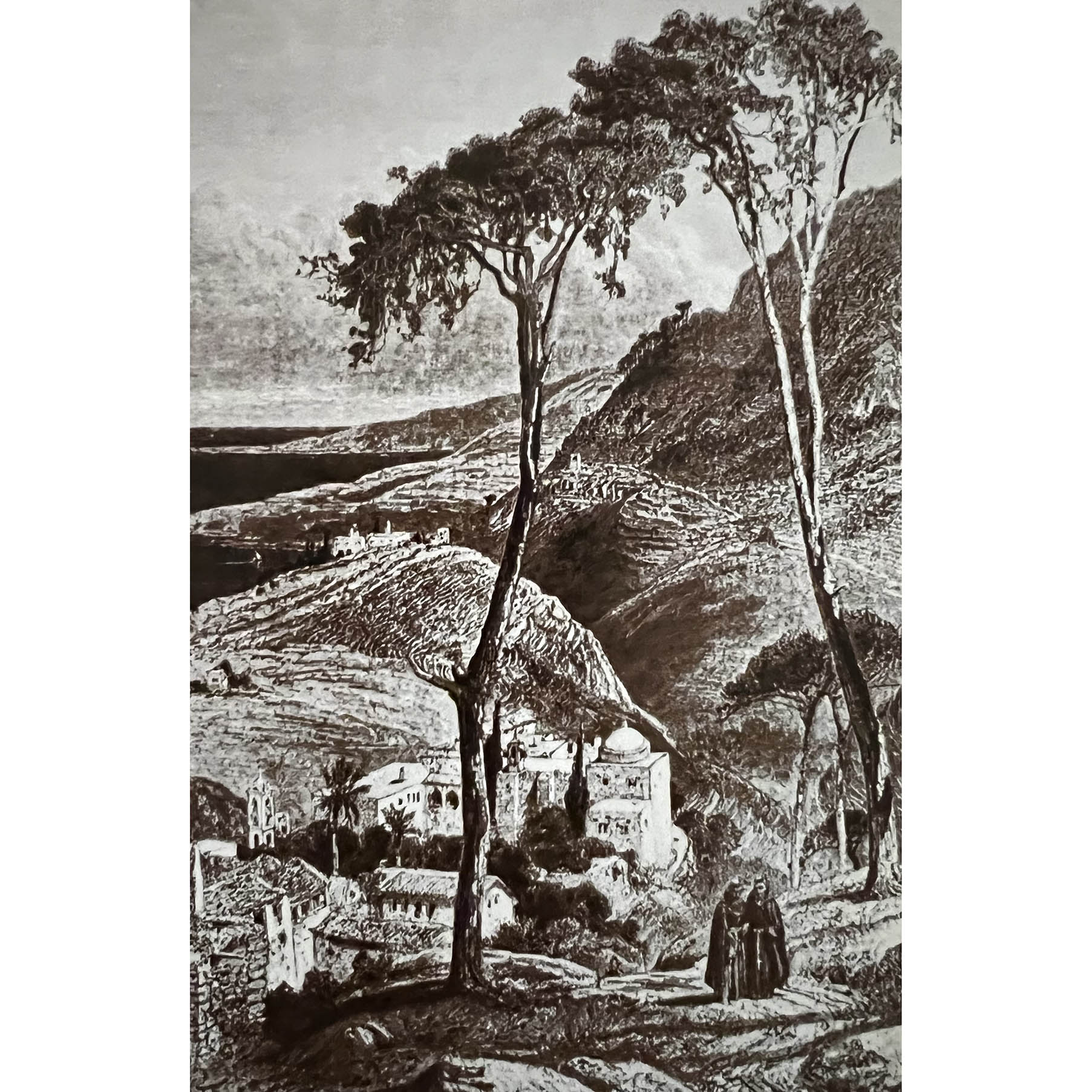

Fra Griphon

In 1468, the Flemish Franciscan Fra Griphon arrived in Lehfed, the village of the 21-year-old Gabriel Qalaï. The missionary had the task of recruiting candidates for their formation according to the dogma of the Roman Church. His choice was fixed on the three young Maronites Gabriel, Yohanna and Francis who, for this, left Mount Lebanon to go to the medieval monastery of the Franciscans in Beirut. After a few months, Fra Griphon took them to the convent of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, where they would spend three years, from 1468 to 1471. From there they sailed for Venice where they were instructed in canonical studies. After Venice, the three Maronites went to Rome to complete their training there. They only returned to Mount Lebanon after 25 years of absence, in 1493. In Italy, they learned Italian, Greek and Latin in addition to Syriac and Arabic, which they already mastered.

Like Bar Hebraeus, Barcleius learned surgery, theology, canonical sciences, philosophy, logic, rhetoric, grammar, arithmetic, geometry, physics, music, astronomy… which he called himself of “sixteen indispensable grades” to be able to discourse on the mysteries of the faith.

The work of Barcleius

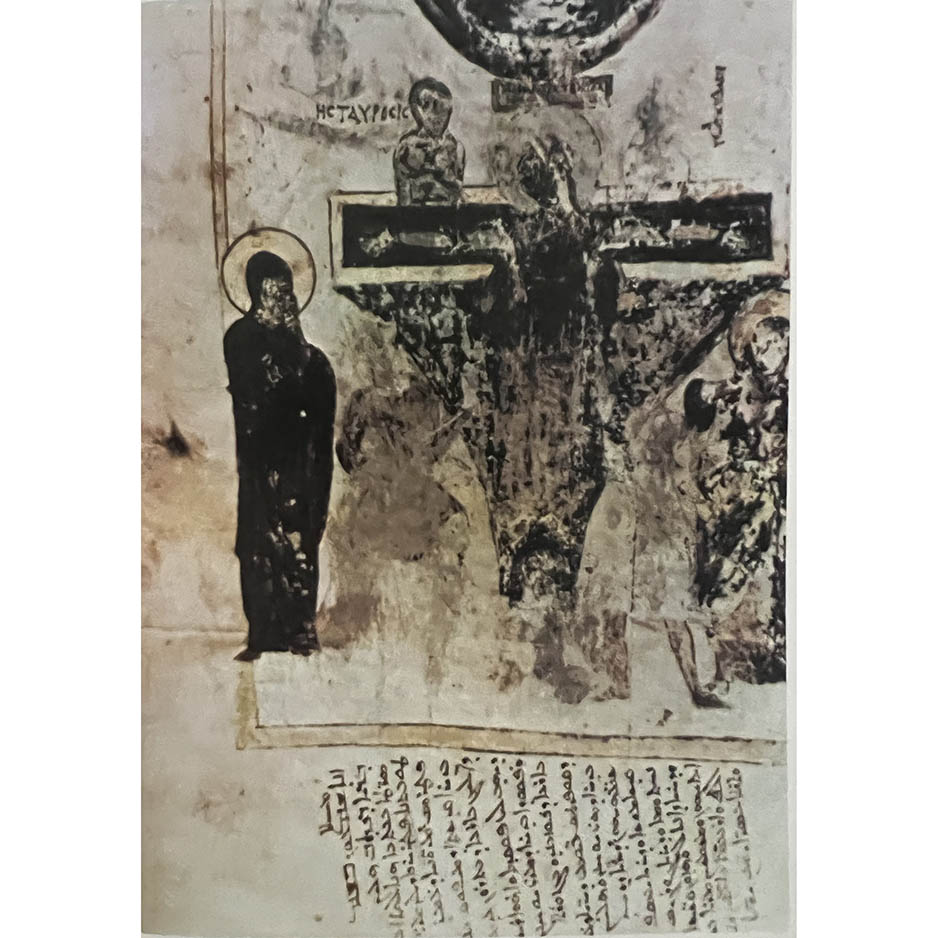

Gabriel Barcleius wrote extensively from the 1490s. His output consisted of translations, transcriptions and personal works enriched with quotations. He transcribed Syriac texts such as homilies by Jacques de Saroug and hymns by Saint Ephrem, letters and speeches on the natures, the person of Christ, and the notion of hypostasis. He translated into Garshoune the correspondence between the papacy and the Maronite patriarchs, from Innocent III (1215) to Leo X (1515) and from Jérémie de Amchit (1230) to Pierre de Hadat (1515).

In his writings, he often returned to Saint Thomas Aquinas, Saint Jerome, Ambrose of Milan, Bonaventure, Nicolas de Lyre and Saint Augustine, from whom he translated extracts from city of god and the treaty of Free will. This last notion, which is found in Saint Jacques de Saroug, is characteristic of the spirituality of the Maronites, and elaborated their approach to freedom associated with their ideal symbolized by Mount Lebanon.

the rebuke

Lebanon was mystical and sacred to Barcleius. He saw there the holy mountain, that of the “pure hearts” erected against the Saracens and the heretical “black wolves” who did not obey Roman dogma. Like any Lebanese from the diaspora who returns to live in the country, Barcleius, who had spent 25 years away from Mount Lebanon, including 22 in Italy, was deeply disenchanted with the homeland he idealized. He was compelled to note the state of intellectual and spiritual decay of his people. He, who had spent two decades vindicating accusations of heresy against his Maronite Church, found himself embarrassed by the people’s ignorance of worship and history. He was outraged by the good-naturedness of certain monks and bishops, and even of the patriarch Simon de Hadat whom he criticized bluntly. This was no doubt what encouraged his appointment to the Maronite episcopal see of Cyprus in 1507, probably with the intention of distancing him from Qannoubine.

Author of poems, zajal and numerous letters, Barcleius sometimes exalted his people there without failing to reprimand them. It’s in his MadihaWhere Praise of Mount Lebanon, that he both glorified and castigated him. He told the story there in an attempt to remedy the exasperating ignorance of the Maronites. He instructed them and informed them about the nobility of their nation. But their mountain, although sacred, found itself castigated here and there. “Bcharré, be afraid and tremble, Bcharré, weep and mourn, Bcharré, repent and straighten up,” he cried. Or: “Maroun married you with conviction, he founded and built you, he raised and instituted you… Maroun is tired because of you”, we read in his letters published by Ray Jabre-Mouawad1.

glorification

At the same time, Barcleius honored the righteous such as Father Dray who “taught me Syriac” he wrote, or Father Maroun whom he nicknamed “the star of Hasroun”. He also did not fail to bequeath in writing traditions transmitted orally, and which glorified Lebanon, such as the motto: “Blessed is he who has even a layer of goats in Mount Lebanon.”

Having lived abroad and assimilated the concept of belonging, Gabriel Barcleius founded the Maronite identity in the complementarity between the Church, the people and the mystical mountain of Lebanon. This notion had been put in place by the patriarch Saint Jean Maron at the end of the 7th century, but could only become a reality by becoming fixed in the writing of history and in people’s consciences. After two centuries of annihilation of Mount Lebanon by the Mamluks, the battered and bruised people had lost their culture, their language and the notion of their identity. Barcleius returned from Italy, devoted himself to the reconstruction of his society through culture and poetry, and of his Church through Roman dogma and spirituality. Although viscerally attached to Lebanon, it was still in exile that he would die in 1516, while occupying his episcopal see of Cyprus.

It was on his work that the patriarch Estéphanos Douaihy would rely at the end of the 17th century, to write his history book. And it is above all by following his example that he began to compose his masterly and founding work on music, art, architecture and liturgy in their permanent relationship to history and the holy mountains of Lebanon.

1- Ray Jabre-Mouawad, Letters to Mount Lebanon by Ibn Al-Qila’iGeuthner, Paris, 2001.