Before he died, Nobel Prize-winning author Isaac Bashevis Singer showed his son, Israel Zamir, his “chaotic bedroom” – a closet filled with so many documents that, in the author’s words, he would have to “live another 100 years” to see all of this in print.

After Singer’s death, the contents of the chaotic chamber – thousands of pages of unpublished manuscripts, notebooks, correspondence, as well as photos and other documents – were transferred to the archives of the Harry Ransom Center of the University of Texas at Austin. Once there, after a long cataloging process, only a few scholars had consulted the unpublished documents.

In 2014, author and literary scholar David Stromberg traveled to Austin in search of an unpublished text by Singer referenced at the end of his novel ” The Penitent“. On that day, when Stromberg enters the archives, he enters the intimate world of the deceased Jewish author.

Born and raised in Poland before moving to New York in 1935, Singer wrote in Yiddish, but ensured that his writings were translated into English – partly by himself – and aspired to publish ever more. In the archives, Stromberg expected to find original texts in Yiddish that would need to be translated, but to his surprise he found a wealth of documents already in English. Singer’s presence was palpable on all these pages, his penciled notes showing that what he hadn’t translated himself, he had closely supervised.

Obtaining permission to edit these documents was far from simple. Stromberg made the pilgrimage twice – in 2013 and 2014 – from his Jerusalem home to Kibbutz Beit Alfa to meet the author’s son. It was in 2014, following his visit to the archives, that Stromberg finally received Zamir’s blessing to compile and publish the author’s essays.

The result is ” Old Truths and New Cliches“, a collection of 19 essays, mostly unpublished in English. In the book’s introduction, Stromberg refers to a 1963 memo written by publisher Roger Straus, which indicates that Singer intended to compile a collection of English-language essays. The selection of translated works, according to Stromberg, reflects Singer’s choices for this book.

Published May 17 by Princeton University Press, “ Old Truths and New Cliches is the culmination of a decade of work for Stromberg. Virtual book launches from Los Angeles and New York featured author Aimee Bender and renowned Yiddishologist Agi Legutko.

In addition to translating and editing Singer’s works, Stromberg is himself the author of works of fiction, non-fiction, academic essays, and four collections of single-panel cartoons. His latest work is a short story-length speculative essay, ” A Short Inquiry Into the End of the World“, published in 2021.

Stromberg was born in Israel to parents from the former Soviet Union, and moved to the United States as a child in 1989. He returned to Israel in 2008, worked in journalism and eventually earned his doctorate in literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. the Times of Israel spoke with Stromberg by phone from his home in Jerusalem the day after the book’s release. The interview below has been edited for clarity.

Author and translator David Stromberg. (Credit: Courtesy)

There’s a lot of unpublished material in this book, and your introduction says it’s just a fraction of Singer’s material that was in his closet when he died. How come so much of this work has never been seen by the public?

There are several answers to this question. After Singer’s death, it probably took nearly a decade to really complete the purchase, transfer, cataloguing, preservation, and filing of the records — you’re talking mid to late 90s already. So there’s already some kind of disconnect – anyone interested in Bashevis Singer had to move on until they got access to this material. But that’s just the technical side of it. One could say that it is the rhythm of research, the rhythm of archiving work. We could also speak of a loss of attention.

Wait, how many documents were there?

It wasn’t just a few boxes. There were 176 boxes. That’s a lot of documents to look at. So that’s part of the story. The other part has to do with prejudice – for which Singer is slightly to blame. He developed this image of an old-fashioned storyteller, and therefore no one was looking for writing in other genres.

And then there’s the idea that he had to publish everything he thought was good, and that he had to leave out the things that he thought maybe less good, or that someone else another told him to be less good. But it’s an approach that doesn’t take into account the contextual aspect of being a world-class professional writer in real time. As good as they are, some things fall through the cracks. In this case, it was his collection of essays.

The problem with archival work is that if you don’t have some kind of intuition, some clue, of what you’re looking for, you don’t necessarily know what’s there. People don’t usually come to an archive saying, “Okay, give me box one, give me box two. I’m just watching. »

And when you walked in, did you feel like you were looking for writings in English or writings that were meant to be translated into English?

I knew I was looking for trials. My doctoral thesis was on ” The Penitent“, at the end of which, in the author’s note, Bashevis mentions an essay which has never been published. I was like, “OK, that’s interesting. One wonders what he is referring to and that can lead to 10 years of research. And you have to seize those moments. These are extremely important times.

When I started, I didn’t know what I was going to find in the archives. I thought that if I wanted to do a collection of Singer’s essays, it would be a translation project – making a selection of his essays in Yiddish, translating them into English and publishing them. But I still had to see what was in the archives. So I went to Austin and ordered every box or folder that looked like it might contain an essay. Gradually, I saw that there was enough material already translated – and translated by or with the direct supervision and editing of Singer himself.

You mentioned there were handwritten notes from Singer on some of them.

Not just on some – everything bears its marks. I consider them to be translations of Singer. Even though other people helped him or made a first draft, he rewrote it so thoroughly in English that, ultimately, he got the final hand of the author.

So I went over there and found these translations, and I was kind of confused, because I was like, “Okay, now what do I do? So I began to order the correspondence and to look box by box, folder by folder, the letters he received to get an idea of his life. Of course, this turned out to be extremely useful as it gave me a writer’s concept in practice.

I have not only seen the lectures, I have also seen the letters from the establishments which have invited him to come and give these lectures. I saw all the organization that was needed not only to translate these works, rewrite and edit them, but also to organize the conferences, take a plane or a bus, show up, get off the bus, enter the auditorium, put down your briefcase, take out the presentation. You suddenly see everything as part of a living context, and not just this kind of disconnected paper with words on it.

“Old Truths and New Cliches”, essays by Isaac Bashevis Singer edited by David Stromberg. (Courtesy Princeton University Press)

In the essay that bears the title of the book, Old Truths and New Cliches“, Singer talks about a writer’s need for spirituality and God. How to understand what seems to be a contradictory message, given its break with religion? I’m not sure exactly how he would define himself – as an agnostic or an atheist, or perhaps a believer in some kind of higher power…

Definitely a believer. There is no doubt that he believes in divinity and a divine Creator. But he is an absolute non-believer in the rabbinical chain of command. Yet he understands that the only way to maintain Jewish identity – at least from his point of view, not on a personal level, but on a socio-historical level – the only way, according to him, to maintain a Jewish identity over centuries and millennia is precisely the rabbinic chain of command that he rejected.

In that same essay, he says you have to have a sense of right and wrong when writing a story.

It essentially speaks of creative and destructive forces. It is not a moralizing form of good and evil. It’s, “Does this action, this belief, this story that I’m telling lead to a creative act or a destructive act?” What he is saying is that literature needs conflicts, that the world is a landscape of conflicts, that we must understand the nature of these conflicts and that, in practice, even if it does not there is no absolute morality, there is a kind of practical morality.

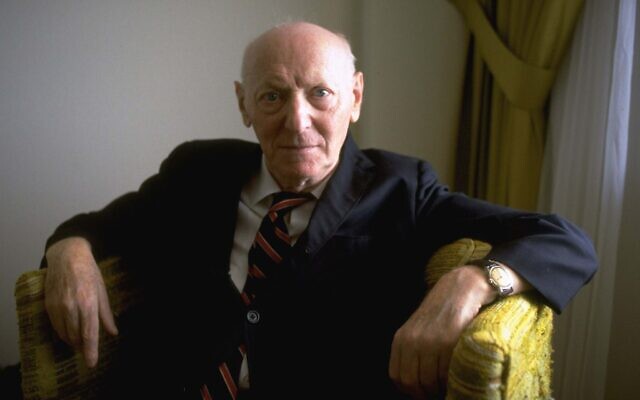

Nobel Prize-winning author Isaac Bashevis Singer, in his Miami Beach apartment, October 10, 1978. (Kathy Willens/AP)

I very much appreciated the conference-essay ” The Kabbalah and Modern Times (The Kabbalah and Modern Times), but I also thought that this guy was embarking on a digression on the Ein-sofor Infinite, and the tsimtsumor absence of Infinity, and the sefirot, or divine attributes, for about 10 pages – in a lecture given at the University of Michigan. Attendees today must know more about Kabbalah than most hippies in Nachlaot.

He has actually written several articles in Yiddish – more descriptive articles, on the differences between theoretical Kabbalah and practical Kabbalah. He talks about the goals of practical Kabbalah, such as healing illnesses, and he talks about theoretical Kabbalah as having no other goal than the search for pure truth. So you’re talking about someone who over many iterations has spent a lot of time reading about Kabbalah and also explaining its meaning to others. He did not need to read Gershom Scholem to write [son premier roman] ” Satan in Goray“He already knew what Kabbalah was. He received it directly from his father, from his grandparents. He was brought up in Hasidic Kabbalah, and that was what interested him.

But continue for so long to address a secular audience?

First of all, it was a subject that interested him. And second, it was, as he says, a way of revealing the contours of his own soul. Again, if you pay attention when reading [la note biographique] ” The Satan of Our Time“, that little note, then you understand that his whole mission as a writer is not to be a cute, famous guy who tells stories.

His mission as a writer is mystical – and that goes back to the prayer and treatise on God that I recently translated and published, where he combines the spiritual mission behind his writing with his literary practice. We cannot separate them. His mission was to preach on the paths of spiritual elevation that can lessen the influence and prevalence of destructive forces in the world.

Academic compiles unpublished writings of Isaac Bashevis Singer