I loved my uncle very much. He was more than an uncle, he was a father when mine passed away very young; he was a friend, an accomplice.

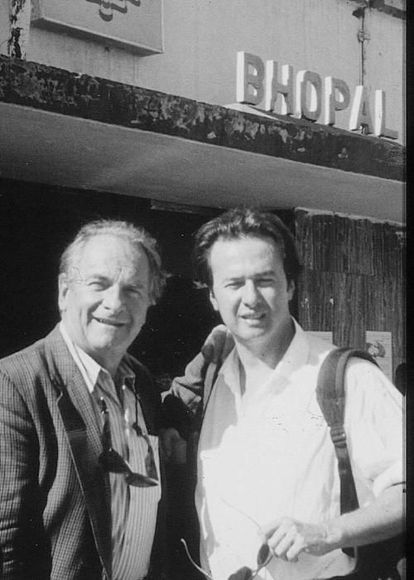

Now it’s goneWhat memories come to mind. What trips, how many shared friendships and good times. I prefer to keep the memory of her before the tragic fall that damaged her brain and robbed her of lucidity, because Dominique died twice, first in 2011, and then on December 2, the anniversary of the Bhopal accident, which did not go unnoticed by the slum dwellers of that Indian city who saw in it the sign of a divine coincidence and lit candles in his honor. And that is the first memory that comes to me, a memory that is also a lesson. Dominique had decided to hand over most of the royalties from the book we had written on the Bhopal tragedy to the construction of a clinic to treat the most serious victims of gas leak poisoning. On the opening day, 22 years ago, I was able to see with my own eyes how a book could improve people’s lives, and that in a concrete, everyday, tangible way. I saw how an intellectual work, which had taken us several years to complete, was transformed into… a clinic. That day I discovered that only with a pen and a notebook could you change the world, or at least influence its improvement.

Dominique knew how to touch people’s hearts. Those who listened to her lectures in Calcutta, Geneva, Jerusalem, or Santiago de Compostela, whether they were rich or poor, white, black, Indian, Christian, Buddhist, or Hindu, all laughed and sometimes cried. Because she knew how to move. And he was a true cosmopolitan, without denying being French, on the contrary. But in Italy, he felt Italian —it’s true that he liked pasta, he was a glutton. India knew her better than the Indians themselves. He was admired and respected by the country’s elite, whose history he had written in freedom tonight along with his soulmate Larry Collins, and was adored and revered by the common people he helped so much.

In Spain he was Spanish. He knew the country not only because part of his family lived here, but also because he dedicated four years of his life to writing a book on the Spanish postwar period, Or will you mourn for me, one of the most beautiful books that have been written about Spain. He learned to love bullfighting, the olive groves that he flew over in the El Cordobés plane and “ramón y queso”, as he used to say with his French accent, and above all the people. He returned from the signatures at the Madrid Book Fair exultant, saying that the Spanish were the most affectionate in the world. Then he wondered how such wonderful people could have fallen into the horrors of a civil war. He always wanted his nephews and nephews to call him “uncle”, even in French, and for us it was always “le tío Dominique”.

He made us, his Spanish family, discover things we didn’t know about, such as the pilgrimage to Rocío, of which he was a fervent devotee. That mix of partying and faith, of adventure and spirituality was so passionate about him that at the age of 80 he did not want to miss what was going to be the last of his dews, even with his arm in a sling. He always regretted that there were so many Spaniards who did not value this pilgrimage, a unique spectacle. I attest, because we made the journey together five times, always on horseback, sleeping in a tent or in a wagon, sometimes out in the open watching the stars, covered in dust, surrounded by people drinking, dancing or praying. For him, that was the real luxury.

My uncle Dominique was an old tree. He offered his branches to anyone who wanted or needed to hold on to them. My grandmother – his mother – told me when he was a child: “Dominique is very generous.” He was right, she, who had transmitted the idea that religion was to love people and protect the weak. She helped her family, and in particular she gave me the opportunity to write a book together when I was unknown to the general public. A gesture that portrays him, honors him and for which I thank him from the bottom of my heart. I like knowing that afterwards he enjoyed my own stories.

He also helped his friends, and the others, the strangers, the faceless poor.

When he turned 50 he wanted to give meaning to his life by dedicating himself body and soul to a formidable humanitarian mission that changed the lives of millions of people (yes, millions, I am not exaggerating) and sadly I feel that he did not receive the recognition he deserved. I have seen him advocate for the poorest to the most powerful in India. I have witnessed how thousands of peasants received him in remote corners of the Ganges delta to thank him for his help, and the envy that he provoked in local politicians, unable to galvanize such crowds. That made him so happy! Yes, he changed the world with the instruments he mastered, with words and with his pen (because he was late with computers).

In the twilight of his life, he, a writer and philanthropist, became a character in a book, a Don Quixote who traveled the routes of the world with the crazy idea of turning it into a place of justice and love.

Have a good trip, “uncle”. Your example lives in us, in all those that your soul knew how to touch. And today I am the one who mourns for you.

All the culture that goes with you awaits you here.

babelia

The literary novelties analyzed by our best critics in our weekly bulletin