But who was Rabi’a al-Adawiyya (713-801) whom Salah Stétié nicknamed “the athlete of God, similar to that of the future Thérèse” by devoting a superb biography to him Rabi’a, of fire and tears (Albin Michel, 2015). “She is the first great figure of Sufism, and it is not insignificant that she is a woman,” noted the Lebanese poet and writer about her.

A major figure in Sufism, endowed with mysterious knowledge, this mystic and poetess lived between 714 and 801 under the Abbasid dynasty, in Basra, Iraq. Asma Lamrabet, Moroccan author of numerous works on reformist thought in Islam, and more particularly on the theme of women, revisits the legend of the most famous waliya (saint), with a view to relaying its universal message, which resonates with the today’s world in an essay entitled Rabi’a al-Adawiyya, mystique and freedom (Albouraq, collection I want to know, 2022).

Rabi’a al-Adawiyya seen through an illumination that illustrates the work of Asma Lamrabet. Photo DR

Early Modernist

“I am from a generation that has seen Egyptian films. This story of a poor little girl, stolen to be sold as a slave and become a dancer to survive, who only prays and then becomes a disciple of the Sufi master Hassan al-Basri (died in 728), remained engraved in my memory as a young woman. “says Asma Lamrabet from Rabat, during a telephone interview with L’Orient-Le Jour.

The publisher Albouraq, specialized in works on civilization

Arab-Muslim, encourages him to unravel the mystery around the famous figure. Among other literary and academic references, Asma Lamrabet is inspired by Anna-Maria Salto Sanchez’s thesis published in 2015, as well as by the book on Rabi’a al-Adawiyya by contemporary Egyptian philosopher Abdel Rahman Badawi, but also by one of the oldest sources, The Memorial of the Saints, by Farid al-Din Attar, dating from the 12th century.

“The first things I read were incredible. There are, around his life, many supernatural stories, sometimes extravagant. I am a believer and a practitioner, but I don’t believe in the irrational,” says the author.

A story relates in particular that on the way to Mecca, the Ka’aba appears in front of Rabi’a, in the middle of the desert. She then said, “I don’t want the Ka’aba, I want the master of the Ka’aba, what will I do with the Ka’aba?” »

“I saw a subversive force in these metaphors perceived as miracles. We tried to “invisibilize” this woman by making her a devotee,” criticizes Asma Lamrabet.

In another account, facing the Ka’aba, Rabi’a issues a frontal criticism of those who reduce the cult of pilgrimage to mere meaningless formalities.

“Here, then, is the idol that is worshiped on earth. Rest assured, God never walked through the door and he never stayed there,” she reportedly remarked.

Thanks to his spirituality, Rabi’a al-Adawiyya was able to criticize those around him and challenge tradition. It’s a fore-

guard who had a speech of astonishing topicality, according to the essayist, who directed, from 2011 to 2018, the Center for Studies on Women and Islam within the official religious institution al-Rabita al-Mohammadia des ulemas of Morocco.

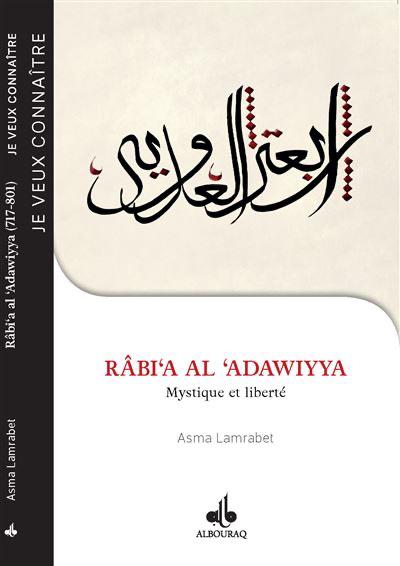

The cover of “Rabi’a al-Adawiyya, mystique and freedom”. Photo DR

The cover of “Rabi’a al-Adawiyya, mystique and freedom”. Photo DR

A role model for the younger generation

By refusing the numerous marriage proposals, Rabi’a al-Adawiyya broke all the taboos of patriarchal society. “She lived in the 8th century like a Parisian today, refusing to submit to any authority whatsoever, especially not a male one. She wanted to devote herself entirely to her love for God, which enabled her to rise on an equal footing with men. »

Rabi’a received many visitors – sometimes even important mystics – in her home for spiritual vigils or political debates during which she allowed herself to criticize. Her great fame also attracted her disciples who joined her to follow her teachings. “The Sufism of that time was a subversive reaction to what was happening in Baghdad,” continues the author. The ascetics marginalized themselves from society to denounce the excesses of pomp. »

This story sums up the essence of the spiritual doctrine of the waliya Rabi’a: a disinterested adoration of all materialism except God.

“There is no worse believer than the one who adores God only out of fear of hell or desire for paradise!

And if there was neither hell nor paradise, then you would not have worshiped it? she would say.

In addition to refusing money and gifts, the saint felt no embarrassment in the face of diversity. “It is a model for our generation which has a restrictive vision of male-female relations, continues Asma. She managed to come out on top by saying there was no spiritual gender difference. Her relationship of love with God was so strong that it freed her from everything, giving her great freedom of speech and action. »

Does the desire to live in harmony with nature and wild animals, to love and respect them, make Rabi’a al-Adawiyya an ecofeminist before her time? Beyond its historical reality, this story indeed reveals a benevolent respect for all creation. Many historians attributed to him a complete abstinence from the consumption of animal products.

One day, while she was climbing a mountain, suddenly all the gazelles that were there gathered around her without showing the slightest fear, apparently feeling safe. And suddenly, as her friend Hassan al-Basri came to join her, all these animals fled. He then asked him: “How is it that the gazelles run away from me and that they don’t run away from you?” She asked him: “What have you eaten today?” “A dish cooked with a piece of fat,” he replies, to which she retorts, “How could they not run away from you when you eat their fat?” »

A universal reading of religion

“Like Rabi’a al-Adawiyya, women have been made invisible from knowledge all over the world. It is important to feminize our reading of history,” argues the essayist.

Currently director of the “gender” chair at the Euro-Arab Foundation of the University of Granada, Asma Lamrabet advocates for greater access for women to religious knowledge. “The condition of women is precarious everywhere. And the Middle East has the worst percentages in terms of gender inequality. Their status was decided, from the beginnings of Islam, by fuqaha’ (Muslim jurists) who perpetuated the patriarchal norms and customs of Persian and Byzantine civilizations. »

For this, the author defends a reform at the level of interpretation and exegesis. “It is said in the Koran that men and women have an identical soul (nafs wahida). I have been campaigning for several years for a reading that highlights the universal values transmitted by the religious text, such as equality, justice or reason. It is a question of human rights and social development”, supports the one who is also an activist within the Committee of Human Rights in Morocco.

“We must put an end to the legal interpretation of the texts. Only a reformist, ethical and humanist reading can lead to the liberation of human beings. This awareness is struggling to emerge in Islam because of the predominance of tradition and the fear of losing one’s bearings”, concludes Asma Lamrabet, who believes that this fact would explain the identity withdrawal of Muslim communities in the West and in the Muslim countries.

All the stories are taken from: “Rabi’a al-Adawiyya, mystic and freedom”, Asma Lamrabet, Albouraq, collection I want to know, 2022, Essay.

But who was Rabi’a al-Adawiyya (713-801) whom Salah Stétié nicknamed “the athlete of God, similar to that of the future Thérèse” by devoting a superb biography to him Rabi’a, of fire and tears (Albin Michel, 2015). “She is the first great figure of Sufism, and it is not insignificant that she is a woman”, had noted to his…

Eco-feminist, vegan, pious and Sufi: who was Rabi’a al-Adawiyya really?