For many it is already the end of the holidays, for others the end of August does not make much difference. The truth is that the summer season is coming to an end and, although the heat says that everything is left for summer except vacations, I want to recommend some short books that you can read at any time, in one sitting, or two.

Here are my proposals:

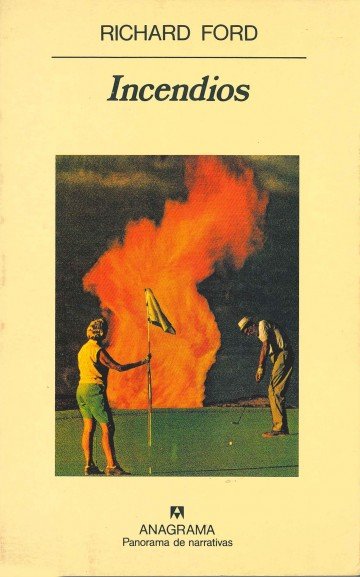

Fires, by Richard Ford

“(…) Don’t let what your parents do disappoint you…”: I highlight this phrase Fires, a novel about the coming of age of a young man whose parents are going through an economic and marital crisis.

The family moves to Montana in 1960, where the father teaches golf lessons, is later fired and after a slight depression decides to go fight the fires that invade the forests near the town where they live. The mother, a vivacious young woman, fed up with her relationship with her husband, begins a relationship with Mr. Miller, a rich, pleasant and lame businessman, all in front of the son, Joe, who is the narrator of the story, and the that makes us witnesses of his abrupt awakening to the world of adults.

The dialogues with the mother are unmissable: “(…) There are times when you have to do something that is not right just to know that you are alive…”; “(…) Perhaps it is nice to know that your parents were not your parents one day…”; “You have to give life a certain intrigue (…) Life is nothing more than an insignificant matter (…) You have to make an effort to make it interesting”: Those are some lines that I was underlining, to give you an idea.

I really liked that the narration of the young man did not lose his voice halfway between innocence and sharpness, as well as the character of the well-constructed characters; each in his own way and at his side.

The author plays with the fires that devour the forests as a symbol, and also throws into the flames the shame, the frustrations, the longings in standby and routine, so that this young man realizes that adults have no idea how to be adults, and that love, from being burned so much, is incinerated, although later some use is made of the ashes.

I felt identified, because I am the only child; because of my closeness to my parents, even though they have never made the mistakes that the parents made in this novel. Children are also the teachers of our parents. Here is a fable about the force of habit, the amplitudes of solitude and the power of dormant passions.

bonsaiby Alejandro Zambra

Short novel —according to the author himself: “It’s a light story that gets heavy”-, Zambra’s literary debut, written in simple language, almost as a summary of what could be a longer novel, like Bonsai, which could be a bigger tree, but it isn’t, because someone decided to spend time maintaining it little.

The way in which their characters intertwine even without knowing each other is something that leaves you thinking about the strange closeness we can have with strangers, how connected we are and how little we really know about everyone and everything.

The story is about a young man named Julio who lies when he loves, without knowing why, and a young woman named Emilia who also lies and then disappears. The two young men are united by an obsession with literature, in a world that seems more and more mediocre. What happens in between and each other’s reactions to losses is the crux of the novel that, for many readers, lacks a concrete story. Julio is the strangest of the characters, a hermit, a misanthrope who prefers to stay locked up watching his Bonsai develop.

Alejandro Zambra’s way of narrating is the true jewel that adorns this book.

The reiterations are accurate, the supposed simplicity that the economy of language that characterizes this narrative work supposes hides a depth that leaves the reader wondering and looking for parallels with their own experiences; Almost all of us have been through something that we do not know how to tell well. The levels of acidity and sweetness, rawness and cooking, certainty and intuition are quite balanced. She reads herself in a “sitting” and is a Latin American beauty in Japanese clothes.

And speaking of Japan, let’s go with:

The key, by Junichiro Tanizaki

Author considered one of the most important and essential of the “novel” genre in Japan, who along with other great Japanese writers changed the course and the way of writing in his country. His name is succeeded by greats like Ōgai Mori, of whom I already recommended The dancer, as well as Akutagawa, Kawabata, Mishima and others.

Read The key in two hours, totally captivated by the novel that at first I misjudged, because I thought it would be bland and slow, how wrong I was!

The narrative is supported by the diaries of its main characters; a man and a woman of mature age and in the midst of a marital crisis. The treatment of sex and sexuality are exquisitely embodied.

I spent eighty percent of the novel remembering and reaffirming a phrase I read many years ago in a little book called Sex, enigma and charm by Carlo Fiore: “(…) try to ensure that there is always some mystery in your marriage…”something that in this novel is revealed in its entirety.

There is voyeurism, fetishism, sex in the third age, jealousy, lies that are not so uncertain and that are somewhat pious, the extreme love-hate for which old marriages swing, the “encounters” with children when they have much access to parental intimacy, and that extreme thirst for youth that the mind has when the body begins to lose vigor. Already at the end of the story it has two important twists that prevent you from getting bored, which I doubt will happen because sneaking into the real and invented secrets of this marriage is exquisite gossip designed to make us better understand our human nature.

For those who are skeptical of Japanese literature, I would advise turning to the literature of Junichirō Tanizaki as a primary exercise. My reverence before this author is one of total respect: what they know as saikeirei.

Silkby Alessandro Baricco

Short and delicious novel, it reads quickly, rather: it ends quickly, but it is of a tempo slow, like an exquisite dinner in a quiet restaurant.

It exudes a certain tenderness, even though it has some strong imagery. It tells of a man whose business was the manufacture of silk in the 19th century, and of his adventures in search of worms and the eggs of those silkworms, from France to a convulsive Japan plunged into riots, fights, traffickers, scammers, among other dangers.

It talks about how the one who has money has more power than the person who governs and the turns that life takes with respect to the material, how “progress” or the passage of time changes things and their meanings , and the drag towards the superficial and the synthetic to which we end up subjected, no matter how authentic we are or think we are.

The way of narrating here is steeped in the brevity and compactness of Japanese expressions. I repeat: it is delicious. For the reader unaccustomed to stories with few frills, this novel will seem somewhat strange. For me it was very refreshing and lyrical.

Tiresias, by Marcel Jouhandeau

Another short novel, from the collection upright smile of which I have already proposed several works, several times. In Tiresias, Jouhandeau narrates the fortuitous and frequent encounters of his protagonist, a man of almost sixty years old, a regular at a brothel where different types of men are waiting for him willing to detonate his spirituality, so prone to rise with carnal friction.

The novel has a lot of poetic and philosophical flight, that distances it from a mere procession of sexual and morbid anecdotes, —which it also has—, but by giving them the gift of meditation, reflection, the study of feeling and thinking, it rises the work.

Each chapter has the name of the lover in turn, and, as a good wise man, in each experience he expresses his teaching, isn’t that what it is?

Here’s a sample story that when you read it and then find out about its author, you know he spent the entire creative process screaming: C’est moithat is, projecting himself onto his protagonist, pouring out his clandestine experiences in other people’s beds, while a cover wife was waiting for him at home who was unable to plug the leak of affections that, after all, did not belong to him: “(…) Permanently touching, avoiding them, the most extreme dangers, that is living…”

As in the Orlando of Virginia Woolf, the narrator of this story feels that suddenly he is also a woman, which does not happen in the same way as in Woolf’s novel, here it is a feeling, a spiritual ambiguity that the body translates from the passive position: “(…) I am without a doubt a man, but also a woman. When looking at me, men unknowingly feel an embarrassment that they transmit to me…”

And to conclude with the projections of the author in his character, I leave you this phrase that from my context I read as a version of the classic and street that they take away my dance:”«(…)Everything that interests me in life is already the pleasure obtained. I won’t apologize to anyone for it.”

This irreverent character is mounted on the myth of Tiresias, eternally punished, toiled by the Gods to see and tell the truth, to know and to guess, to offer us his story.

I hope that one of these five proposals motivates you to read something soon. I repeat: they are gone in no time and, with nothing more to add, I say goodbye until next week, to see what “Libbrazos” I give.