By Domingo Valentin Castro Burgoin

They were not many times in their adult life that they met. Each one of them followed the course of his destiny and the personal cultivation they made of him. Different and equidistant circumstances from each of their lives guided their destinies. But the inflection occurred in childhood and was forever sealed in friendship, remained in youth and strengthened in the maturity of his years, despite the casual and sporadic of their encounters.

Like many, I believe in spirituality and that death is a door that opens to an existence other than this earthly life, and I am sure that on January 10 they shook hands again in the warmth of the spirit, to tell each other anecdotes of their life in La Paz and to perceive together the peace of eternity, touched by the indelible memories they left in us as children, in their other relatives and in their friends who remain here until God allows us.

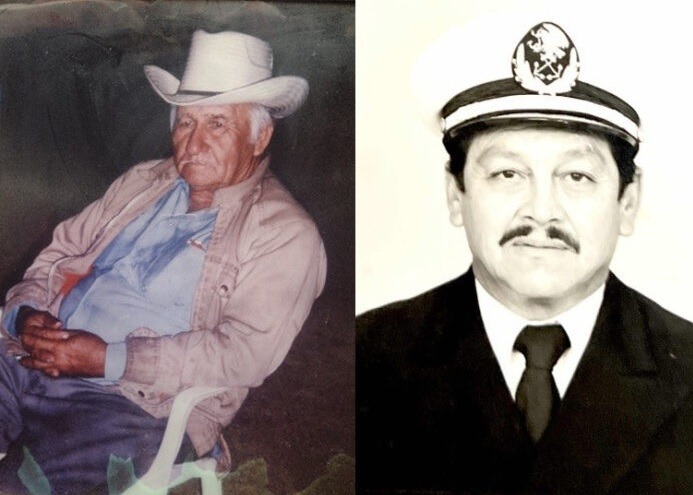

I will make a brief narrative of that friendship between Dr. Marcelo Torreblanca Sánchez (March 5, 1937-January 10, 2023), recently deceased, and Saturnino Castro Sández (November 29, 1932-March 5, 2007), whom -after fifteen years of physical absence- we continue to call his children: my Dad.

Dr. Torreblanca lived almost 86 years. Saturnino Castro almost 75 years. My Dad was four years and months older than him. Seventy years apart, on March 5 (1937) Dr. Torreblanca was born and Saturnino Castro died (2007). A symbolic day.

More than eighty years ago my aunt Elisa, her older sister, brought my father from Agua Caliente, currently a common land in the Delegation of Santiago, to live with him and her husband Felipe Cortés in La Paz, in a rented house near the former Salvatierra Hospital. The little house, built with the typical brick that distinguishes La Paz from yesteryear, was destroyed about four decades ago, but it continues in my memories as if it were still there. Some years ago my uncles Margarita, Guadalupe, Loreto, Arnulfo, and of course Elisa and Saturnino, who was the youngest of all, had been orphaned. After their mother Rafaela Sández died, their father Leocadio Castro left a few years later to make a new life in the Santo Domingo Valley, and they had already been cared for and raised with their aunt, the teacher Guadalupe Sández, who would later live in Santa Anita, near from San Jose del Cabo. Undoubtedly, difficult years due to the practically loss of both parents, the difficulties were accentuated in those years where it was not easy at all due to the scarcity of all material things, in poverty, in the absence of schools and jobs in the rural life they led, but Those difficulties were offset by family solidarity and the absence of serious social problems such as those that currently abound. I do not have the data of how many years they lived with my Aunt Lupe Sández, as we always mention. Probably about three or four years, until Elisa got older, she got married and was able to bring my Dad with her, as I say. The other sisters Margarita and Guadalupe also got married and stayed in Agua Caliente. Arnulfo also did the same and Loreto went to break through the cultivated fields in Mexicali, and some time later my Dad would follow him.

Saturnino in his childhood, living in La Paz, did not finish his primary school, but he learned enough in Arithmetic to take care of his changarros as an adult and in the National Language and Civics to read and write, to later demand his rights for the ejidal land. Due to the difference in age with his friend Marcelo Torreblanca, perhaps it was not in elementary school that they met. However, the need to help support the family that my Dad had surely made him approach and treat Marcelo, then also a child, because running errands, selling empanadas, the almost adolescent Saturnino came to work at the house of the Rosa Sánchez de Torreblanca teachers. and Marcelo Torreblanca Espinoza de los Monteros, Marcelo’s parents. He commented this to reflect the differences in the family environment of our characters and to exalt the differences in the value of their meeting and their friendship.

La Paz then was a small city, but with great affections. All the families knew each other and the barely perceptible social differences did not produce borders in the treatment of people. An environment of relationships like a big family, where science and technology that had stopped due to the years of the Great Depression in our neighbor to the north, were barely perceptible in some mercurial light that illuminated the few streets of La Paz, and they allowed us to see on moonless nights an austere boardwalk, palm trees swaying their branches, and its tax docks where the stevedores had sweated their backs since dawn. It was part of the La Paz atmosphere that the notes of a piano were heard in the center and the family sitting on the porch; and of course, locals and strangers enjoyed the air of the Coromuel without noticing the absent contamination of the bay, if perhaps some oil stain spilled on their hulls by the engines of medium-class cargo ships, ships that once inspired the young man. Marcelo Torreblanca and that years later, with other fretwork and insignia, he would manage to serve as a sailor. And it would be after or parallel to this that the young Marcelo Torreblanca would become a dentist, of course going to study, without losing his small-town origin, his simplicity and his people skills, because together with other medical professionals, such as the Dr. Francisco Palacios Ceseña, also deceased a few years ago and a great friend of my father Saturnino, the steps up the social ladder were not an obstacle to continue being people of affable and simple treatment. I can be inaccurate, but not fictitious.

I could imagine the good treatment that the parents of the esteemed doctor Marcelo Torreblanca lavished on my father in his needy childhood and youth. Undoubtedly, after finishing his work at his house, they invited him to eat “a taco”, my Dad used to say. And perhaps clothes and some utensils they would have given him. Signs of his kindness and understanding for whom life gave him lemons and with them he made lemonade. Because with those harsh conditions of orphanhood and economic need, as soon as he was able to emigrate to the north of the peninsula, he did so, and he even arrived wet to the agricultural fields of California, not exempt from adventures and dangers at his young age. .

And that treatment that I imagine he received, I deduce from a fact as certain as it is emotional: I was fortunate to be a student of the teacher Rosa Sánchez de Torreblanca, first or second grade of the Industrial and Commercial Technical Secondary School number 1 “Professor Concepción Casillas Follow me”. Our distinguished Spanish teacher, petite, elderly, with her big glasses, her short Chinese hair, little steps, went up the stairs of the new ETIC building on Isabel La Católica street, then the last paved street and the dusty Reforma street. Loaded with her books, with her notes, suffering from some disease, she fulfilled her duty as an apostolate: giving us the morning class, leading us through the ins and outs of the language and knowing the syntax, prosody and spelling. We were twelve or thirteen years old her students. It was 1970, 1971, and that scene in the morning two or three times a week did nothing less than move us. I am not exaggerating when I say that sometimes she was on the verge of falling or fainting in class, but not to make her give up her efforts and her responsibility, until she retired.

In this context, after the death of my father Saturnino, knowing of the friendship between them, that when I met Dr. Torreblanca, the first question was about his friend Saturnino, my answer was: He is doing the same thing there, going and coming to Agua Caliente, cultivating the land and selling in his shed. He did this until the disease finished his strength and he could not return independently to his beloved land, which in the distance, from Las Torres in Santiago, he could see his homeland near the mountains, and his countenance was happy passing the hollow, the palm groves, the wide stream and the guamuchilares of Santiago.

While Dr. Torreblanca continued to attend to his patients, reading until his tired eyes and the disease also spread a cloak of darkness, like a curtain that prevents seeing, but which allowed him to relive the memories that remained as landscapes in his neurons, as living paintings of the scenes that his memory kept from his personal development, from his parents and his children, from his family and his friends. And among these memories, I am sure and I know, that the friendship and perhaps the adventures, the language, the irony and the malice, his expressive turns of man of the field and the ranch, of my Apa Saturnino, like those that Juan Ramos eternizes in his Sudcaliforniano Anecdotario, they were with him and went to meet his friend who was opening the path of luminosity, perhaps not on the same day of January 10 as his death, but perhaps one or more days, when the spiritual and love that he had with his parents Rosa and Marcelo, gave the esteemed doctor Torreblanca a space to feel the presence of one another, without the scourge of the disease and the temporal concerns of one and the other.

What examples of lives, and of sincere friendship! Thus, pure and without mixtures, because there was no more interest and purpose because she was born free of them, given by circumstances and destiny.

Both have already left La Paz, but they have remained in peace, in the peace that faith and certainty gives to those of us who are still here, still in pain and sadness, in this present life, that God exists, not only in our minds, but in eternity.

Rest in peace.

In memory of Marcelo Torreblanca Sánchez and Saturnino Castro Sández