The life of Jesus in the cinema would have generated only a series of crusts, on the Hollywood kitsch side or on the illustrated catechism side, if Pier Paolo Pasolini had not signed in 1964 a masterpiece, embodied and poetic, political without being sacrilegious , who had the audacity to please – almost – everyone: believers as well as atheists, Marxists, Freudians… Pasolini, carried throughout his life by Marx, Freud and Christ, was also going to die martyred eleven years later for telling the truth in an Italian society that didn’t ask for so much.

Successor to Accattone, Mamma Roma and a handful of short films and documentaries, The Gospel according to Saint Matthew (Il vangelo secondo Matteo) marks a decisive step in the filmography of Pier Paolo Pasolini. This adaptation of the Gospels ratifies the break with neo-realism, latent in Pasolini’s first two fiction films, and dares to tackle head-on the question of the sacred which haunts the filmmaker-poet from Accattone.

For Pasolini, The Gospel according to Saint Matthew becomes the film-manifesto of this cinema of poetry that he has already approached in his first attempts. He evokes a “stylistic magma” about The Gospel according to Saint Matthew, which effectively systematizes the profusion of technical processes that derogate both from the canons of classical cinema that Pasolini ignores and from the aesthetic precepts of modern cinema born of Rossellini’s neo-realism, which Pasolini intends to transcend, or rather transgress. Thus, Pasolini in The Gospel according to Saint Matthew uses the zoom, wide angle, breaks up the faces in very close-ups, films many scenes with a handheld camera like a report, shoots in Palestine but also in southern Italy, draws on his discotheque excerpts from Bach, Mozart, Webern, Prokofiev mixed with “spirituals” and the Congolese “Missa Luba”. He broke with the principles of direct sound and the raw recording of reality dear to Renoir and Rossellini by systematically dissociating the image from the sound, the face from the voice, by employing non-professional actors whom he then had dubbed by comedians. Such principles were already present in Accattone and Mamma Romabut they are pushed to their climax in The Gospel according to Saint Matthewby the intensity and frequency of their use.

Pasolini is both the heir to neo-realism, the witness-actor of a pivotal moment in the history of cinema (the new European waves), and a great iconoclast. Like other writers who have become important filmmakers like him (Pagnol, Cocteau, Guitry, Duras), his artistic marginality and his literary origins give him an extraordinary freedom of invention and a natural ability to break the rules of directing to create new ones, limited to personal use. Whether The Gospel according to Saint Matthew appears as an aesthetic manifesto, this does not in any way imply that Pasolini erected into dogmas principles that he hastened to question or eradicate in his following films, aware of the ephemeral and perverse nature of the concept of cinema of poetry opposed to the prose of more conventional or commercial productions. It is paradoxically by filming the life of Christ that Pasolini opts for the most impure cinematographic form. It is certainly not a question of blasphemy or provocation on the part of the filmmaker who scrupulously respects the scriptures, but of a refusal of pious illumination and a search for truth and life in art. The film is part of a continuity that is more pictorial than cinematographic. The frontality of the frame, the characters placed in the center of the shot, frequent style figures with Pasolini, come from certain painters of the trecento, Masaccio or Giotto, whom the filmmaker admired, and the beauty of the “models” chosen evokes Byzantine icons. Some scenes from Accattone and Mamma Roma already reached a religious dimension in the Christian journey of its characters, which relived the passion of Christ in the slums of the Roman suburbs, with this mixture of sacred art (painting, music) and profane triviality. But Pasolini breaks in The Gospel according to Saint Matthew this permanent pictorial temptation by a black and white with violent contrasts and a very mobile image which only accidentally freezes the bodies in Sulpician postures.

There remains the notion of the sacred. Why did Pasolini, intellectual and communist artist, want to illustrate the Gospels? Although an atheist, Pasolini considers faith as “the extension of poetry”. He accesses a form of mysticism in the contemplation of men and the world. His cinema of the sacred differs from the spirituality of Rossellini or the Christian fictions of Fellini’s first period (la strada, He can’t, Cabiria Nights). Pasolini maintains a real veneration for a primitive form of religion, which he will try to find in a cinema itself archaic by staging allegories located in a prehistoric, medieval or fantastic past. Pasolini chose to film the Gospel of Matthew, the most revolutionary of the evangelists according to the filmmaker, “because he is the most realistic, the closest to the earthly reality of the world where Christ appears”. Marxism and the mysticism of Pasolini come together in this nostalgia for Catholicism as a popular belief, with the childhood memory of the fervent faith of his mother, of peasant origin, opposed to the hypocritical and bourgeois religiosity of his father. The filmmaker will go so far as to entrust the role of the mother of Christ to his own mother. Whether The Gospel according to Saint Matthew occupies such an important place in the life and work of Pasolini, it is because the film takes on a meaning that is at once aesthetic, political and autobiographical. Pasolini reconciles chaos and harmony, purity and impurity, the sacred and the profane. But he also manages to make a universal vision of the Gospels coincide with his intimate identification with Christ.

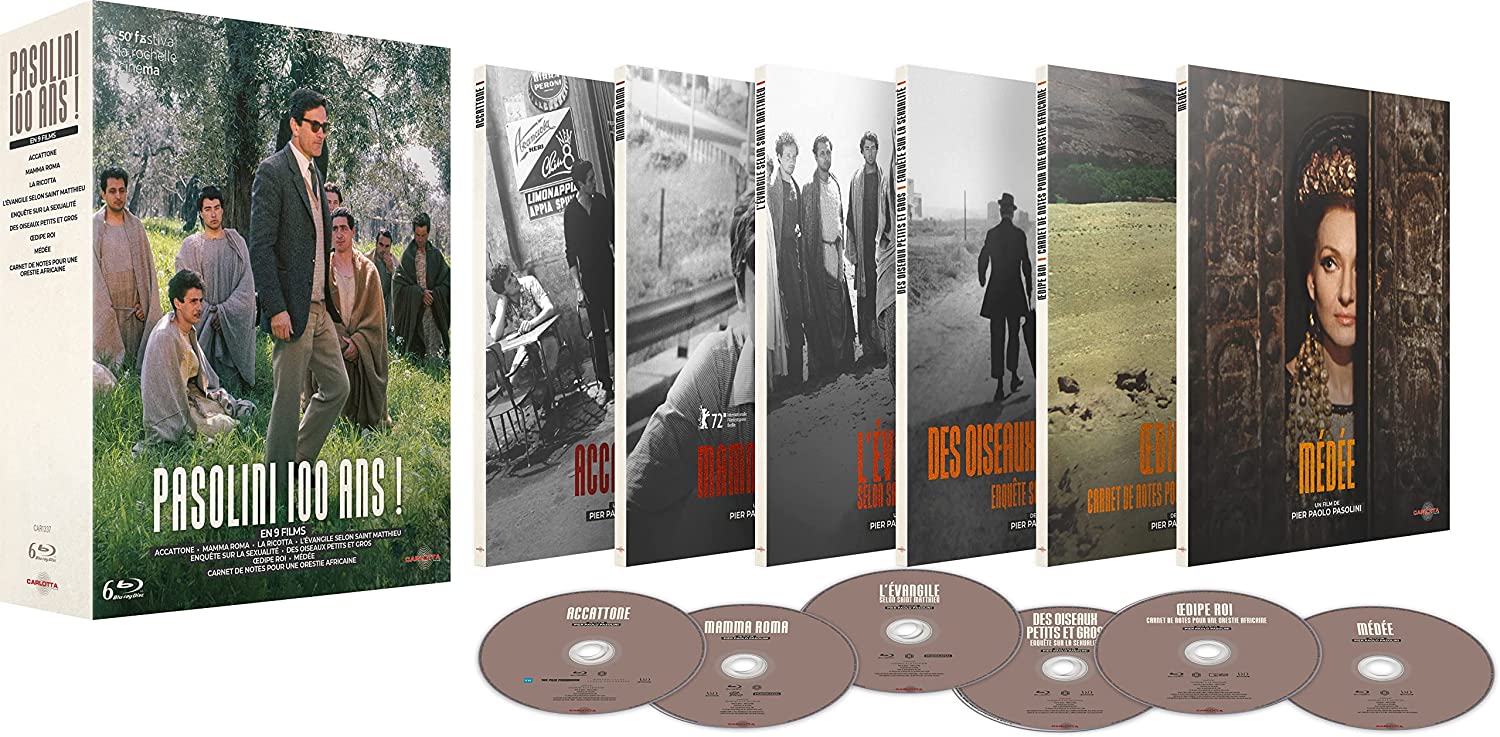

Carlotta offers a Pasolini box set published on the occasion of the centenary celebration of the filmmaker, born March 5, 1922 and murdered November 2, 1975. In addition to The Gospel according to Saint Mattheware gathered in this box Accattone, Mamma Roma, Ricotta, Birds, big and small, King Oedipus, Medea, Sexuality survey, Notebook for an African Orestesin restored versions and accompanied by quality supplements.

We have already written about Mamma Roma, Ricotta and Medea in this blog.

Carlotta had previously edited the box set of “The Trilogy of Life” bringing together The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales and The thousand and One Nights.

The Gospel According to Saint Matthew by Pier Paolo Pasolini – Olivier Père