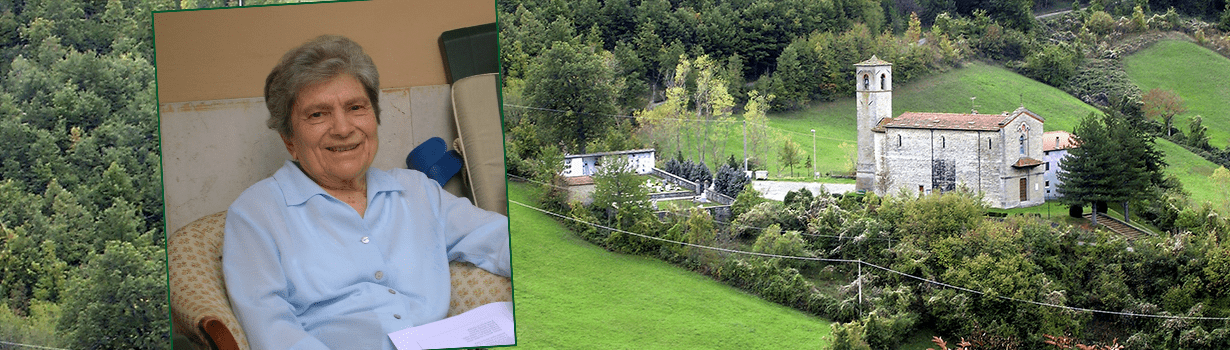

On December 31, 2022, Luisa Del Zanna, one of the first focolarine in Florence, passed away. She was born in 1925 into a Christian family with 8 children. Knowing the spirituality of unity, she immediately made it her own. In 1954 she became part of the focolare in Florence. In subsequent years she saw the birth and followed the communities of the Movement in all vocations and dedicated herself to them with love, intelligence, sensitivity and delicacy. From 1967 she will be in Rocca di Papa where Chiara Lubich called her to take care of her secretariat and the archive, which she coordinated until 2007, and the birth of the Santa Chiara Center, for communication, together with Vitaliano Bulletti.

“Keeper of the ‘treasures of the Focolari’ – reads a 2008 article in Città Nuova – Luisetta, a name that caresses you, that makes you think of a delicate and kind creature. And it truly is in her tiny figure, Luisa Del Zanna, one of those people who are usually entrusted with important tasks due to their discretion, competence, loyalty, whose value is not always understood because they do not appear but without whom certain gears would end up jamming…”.

Neitherher first years of life in the hearth she worked as a teacher in a small village in the mountains which she reached by traveling part of the way on the back of a donkey having to stay out all week. It is precisely of those years the experience that you wrote in 1958 that we publish in continuation.

“Please, the road to Bordignano?[1]”

After four hours by bus I had arrived at the capital city of that town which I had not been able to find on the topographic map (scale 1:100,000). No news agency was able to report it, nor did the timetables of the various means of transport mention it.

And yet, the nomination sheet was clear: “Your Lordship is invited to take up service on Friday 7 October in the elementary school of Bordignano in the Municipality of Firenzuola”. And the name was written in block letters, you couldn’t go wrong.

The person I had spoken to – a tall, robust man – looked at me questioningly: “What did you say?” and she made me repeat the question. He thought he had misunderstood. Then he pointed away: “Do you see that hill over there? Behind there are two more and then there is B…. I’m going there even now to bring the mail.”

I didn’t hesitate for a moment to understand that he was walking there: the boots he was wearing and his tanned face made him clearly visible. I had a moment of dismay: I looked at that hill, at that man’s boots, I understood that there were no other means, I gathered my courage.

“I’m coming with you,” I said firmly. The postman did not seem to understand, as before, but I set off and followed him. It was three long hours of travel, interrupted only by brief moments of rest at the top of the steep climbs; there were strong gusts of wind where the valley opened.

Finally, I arrived: three stone houses lined up and up, at the top of a tree-lined street, the church with its bell tower.

Finally, I arrived: three stone houses lined up and up, at the top of a tree-lined street, the church with its bell tower.

I greeted an old man, sitting with a pipe in his mouth, on the doorstep. I told him I was the teacher. He stood up and moved to accompany me. We entered by a broken door into the second of those houses in a row, all the old man’s property; the first was the shop, equipped with everything (except for a few things that I didn’t have and that I really would have needed).

There were studded boots, matches, mousetraps (of many species, those), stale bread, notebooks, in short, everything.

We climbed a ladder and entered the school. A large room, a few desks piled up in a corner (I had never seen any of that kind: even six children could fit in just one of them), a messy chair, a broken blackboard: that was all the furniture.

– Her home is here – the old man explained to me – she can be happy! This year there is running water. I had it put on myself, at my expense!

He ushered me into a kitchenette; the unlit fireplace stood out in one corner. I was cold. It was starting to get dark: I looked for the light switch to turn it on, but it wasn’t there. (I learned, in the days that followed, to use the carbide lamp and to work and write by the light of that quivering tongue of fire).

That same day I looked for the Pievano (I learned that the Pieve was his church, the most beautiful of those in the valley and on the surrounding hills) and I begged him to ban Sunday Mass, which was starting school.

“Eh, Miss, it’s harvest time. Now there are chestnuts and then olives; the guys help a lot in these jobs. We will talk about school – she added – in January ”.

It seemed impossible to me. I had learned for some time not to retreat in difficulties, on the contrary – they told me – they serve as a launching pad – and I saw that it was true. I found another way to let people know I had arrived. I identified the homes of my pupils among those scattered, isolated houses and went there.

The first was the home of Angiolino and Maria. I have a vague memory of black and smoke left of that. There was Maria crouched in a corner in the ashes of the hearth (she had a pain in her throat), she held her little arm up to her face so that I wouldn’t see her. Angiolino was standing: in a corner with his head bowed, he was following the conversation I was having with my mother. During the interview I learned about the distrust of those people in the school and even more in the teacher.

I listened a lot, in silence. I made an effort to understand that woman’s speech in a hard, resentful, almost incomprehensible dialect. I learned that the boy had left school two years ago, without having completed his elementary studies, due to the pranks he perpetrated to the detriment of the teachers. I said a few things: I had come for them, the school was free, the boys would have the afternoon off to help with the work in the fields. “We will see – said the woman – I will send Maria”. As I said goodbye, I said goodbye to the boy: “I’d like to make the school beautiful for the little ones who will come, if you can come and help me… I’ll wait for you”.

There was no need for many more invitations.

The children arrived one by one, their siblings in pairs, uncertain, fearful. They had given each other their voice by meeting for games, in the fields, while tending the flock, or by being hunched over together in the woods to collect chestnuts. “Come you too? It’s beautiful, you know!” “It feels good, the teacher doesn’t beat!”

The school became welcoming in a short time with Angiolino’s valid help. October nature offered rich ornamental material in the varied color of its leaves. He began the work. I had met a teacher: her school was inspired by that of the Divine Master. I wanted to do like her too.

In the previous few years of my teaching I had tried to get to know the most popular pedagogical methods and make them my own. But each year ended in a sense of failure and defeat. But this was the pedagogical method of a God: it could not fail.

I established my relationships with the students and the relationships of the students with each other on Jesus’ command: “Love one another…”. It was the basis of all the work that year. The school became a little paradise. The favorite book was the Gospel and the intelligence of those children, unused and closed to human reasoning, opened up to the evangelical logic with surprising spontaneity.

That method was challenging. “Pro eis sanctifico me ipsum” (pand they sanctify myself), Jesus had said so, otherwise it would have no effect. It was a battle and it was necessary to be strong; however, there was the Food that gave her strength and I never did without it. Even when the funeral offices in the distant parishes required the presence of the parish priest and he left on horseback well before dawn, the appointment in the little church was not missed to have Jesus, and it was worth braving the dark and the barking for this some dogs along the path.

At the end of the year, I realized that the evangelical life of the little ones had not stopped within the walls of the school, but had spilled over into the home, into the family. I noticed it from the grateful greeting of the parents who had not remained indifferent to that breath of joyful life that the children brought among them when they returned. The rough exterior that had made them seem insensitive to me had disappeared from souls and, unconsciously, that same life had entered into them.

Experience of Luisa Del Zanna

[1] Bordignano, in the municipality of Firenzuola (Florence, Italy).