Fifty-two years ago, on November 25, 1970, shortly after noon, the Japanese writer Yukio Mishima committed seppuku (ritual suicide) in the offices of the Japanese Ministry of Defense in Tokyo.

The openly declared reason was the opposition to the decadence of his country and to the article 9 of the Constitution imposed by the US invaders which stated: “the Japanese people renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation” and for this “the forces of land, sea, air and any other potentially military force”. Included was the dismissal of the emperor, the denial of his divine nature, the foundation of Japanese culture of the time; the cancellation of the nobility, reduced to the rank of bourgeoisie; the occupation of the country by the US military and the installation of US military bases. The imposition of democracy was, for the writer, the expression of decadence, submission, the end of Tradition and the spirit of Bushido and Hagakure.

A suicide that was an act of rebellion shown to the world with ink and blood, with his action and with his work. On the day of the event, Mishima had delivered to his publisher the last volume of the tetralogy The sea of fertility, finished writing in March with the handwritten phrase, on the last sheet, “November 25, 1970”, as if to sign the spiritual testament . After entering the Ichigaya barracks (headquarters of the self-defense forces) together with four of his comrades from the Tate no kai (the “League of shields”, a private militia made up of one hundred young men), he occupied the office of General Masuda, who to a chair. From the balcony Mishima harangued thousands of soldiers who had come from all over the barracks, and was filmed, in those tragic moments, by TV and photographers. It was his last speech, in which he exalted the spirit of Japan, the emperor, expressed his condemnation of the 1947 Constitution and the San Francisco treaty (which provided for the renunciation of the army and the assignment of defense to the USA) . His last words were: “We must die to restore Japan to his true face! Is it good to have life so dear as to let the spirit die? What kind of army is this that has no nobler values than life? We will now testify to the existence of a higher value than the attachment to life. This value is not freedom! It’s not democracy! It’s Japan! It is Japan, the country of history and traditions that we love”.

The speech was partly disturbed by the shouts of soldiers and the noise of a helicopter circling over the barracks building. At the end Mishima returned and committed seppuku. His trusty Masakatsuo Morita, one of the four young men who accompanied him was behind the writer and promptly swung a katana blow to cut off the head, as required in the practice of ritual suicide of the samurai: he missed his aim, hit the shoulder and neck without being able to ‘intent. Blood spread on the floor and another member of the League of Shields intervened, Masayoshi Kaga, who concluded the rite with a clean blow. Morita, to erase the shame he felt for his inaccurate gesture, committed seppuku.

Mishima was the greatest Japanese writer, the most translated, the most studied, invited to give lectures and lectures in many universities. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize for literature four times. His first novel, written at the age of 24, was a great success: it was Confessions of a mask and Mishima became the symbol of the restoration of the traditional ideal, against globalization, massification, modern democracy with stars and stripes. In his works this vision of the world emerges as a reflection of love for Tradition and for the emperor, fidelity to the codes of behavior of the Japanese community, the superior vision, its legends, myths, rites, symbols.

The concept of Emperor did not refer to a political figure or the highest representative of the state, but referred to a divine expression of Japan. In 45 years of life Mishima has written a hundred works and the judgments on his work are conflicting. The day after the event, the Japanese newspapers reported, among other things, the comments of the Japanese prime minister, Eisaku Sato, who defined that gesture as “madness”, with the aim of belittling the writer. Secretary of State Nakasone stressed the need to keep extremists at bay because with these actions they put democracy and the Constitution at risk. The “Mainichi Shimbun”, a newspaper with a circulation of millions, stressed that it was an “act of madness”. The “poem of the abandonment of the world”, composed according to the classical form in 31 syllables, was the last note a samurai left. The one written by Mishima read: “Human life is short, but I would like to live forever”.

Critics usually define him as an aesthete, a dandy, like Montherlant, a decadent conservative, a nationalist. The adherence to Tradition, to the Myth, to the ethics of the samurai, demonstrate well why Mishima remarked his distance from politics. He fought his battle for a traditional worldview and sealed his fight with one last act.

But to understand Mishima’s work it is necessary to understand his vision of the world which, as mentioned, the critics did not consider, reducing everything to seppuku, body care and his so-called nationalism. In-depth analyzes are rare.

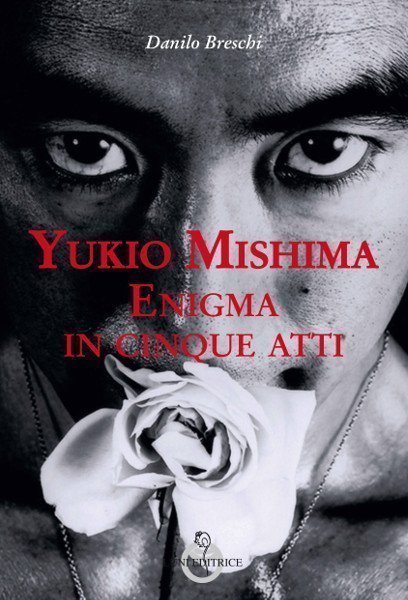

Kimitake Hiraoka, this is Mishima’s real name, had instead performed an important literary, and more broadly cultural, function: a scholar of both traditional Japanese and European culture, he had been a sort of bridge between the East and the West. The search for characters and the structure of the plots of his novels and short stories are influenced by his solid knowledge of European literature. A mixture that showed well how his literature in many ways detached itself from that of his teacher Yasunari Kawabata and from the other writers of the twentieth century, elaborating a set of ideas that draw on the Japanese Middle Ages, with a rigid hierarchy, a reference to Tradition, and a warrior spirit. A mixture of antiquity and modernity, tradition and becoming, which has made something new out of his work. Danilo Breschi, professor of political doctrines at the University of International Studies in Rome has published this book dedicated to Mishima trying, in five chapters, to align and unravel some mysteries of Mishima’s poetics starting in reverse, from the epilogue to end with the fifth chapter dedicated to the beginning, to the prologue.

In the preface, the author declares his interest in the Japanese writer and explains that his is a study which is also a tribute and a divertissement at the same time although it makes use of a scientific slant. In short, something in between an exercise in style and an invitation to read, a “circumnavigation of an enigma” despite the figure and writings of Mishima have kidnapped the imagination and the intimate feelings of generations of young people. The purpose of this essay is to focus on some aspects of Mishima’s poetics and worldview by removing the writer from the stereotypes that circulate in the West, especially in the USA, for example that of the Japanese who makes harakiri, the pop icon who an image of the defeated Japanese who gives his sacrifice to the gods, the homosexual who mimics dandies like d’Annunzio and Wilde.

Precisely because his literary production is endless (about one hundred works in twenty-five years), multifaceted, and touched upon multiple themes, Breschi has chosen to address only a few, the main ones. In the five chapters he reviews the most characteristic aspects of the Mishimian vision. First the theme of suicide. It has become necessary for the writer to give a deeper meaning to his life, so much so that the chapter is presented as an “epilogue that announces itself as a prologue”. In short, a new beginning, he who had seen his world destroyed by US bombing, cities obliterated by the atomic bomb, the new Japan redefined according to the dictates imposed by Americanization and the US administration. A way to bring to mind a world that has now disappeared and been put in a position of not being able to resurrect from the San Francisco agreements which provided for the disarmament of the nation and, above all, the declaration by Emperor Hirohito not to descend from the lineage of the gods. Mishima, inspired by the philosophy of the Greeks and accepting life, in a Nietzschean way, created a symbiosis between body and thought, building a body like that of the Greek statues in the gym and at the same time refined his thinking which in his writings represented adherence to the spirit . In short, he chose and gave himself an education imparted by steel, the sword; from exercise, the gym; from writing, composition. A construction nourished in parallel, as already mentioned, also by Western thought, by Nietzsche, by the Greek philosophers. Breschi notes that a glittering body, with tense and wriggling muscles, was as anti-modern as the ancient languages, the so-called “dead” languages. He re-proposed “an ideal of an aristocratic man, well educated and warrior”. In short, he found “his way, that of the samurai, a path of tradition, even more sublimated as it is mythologized by the ritual of writing”: specularly he addresses the theme of decadence, treated, among others, in books such as Madame De Sade, La Kyoko’s House, Spiritual Lessons for Young Samurai, Patriotism, My Friend Hitler etc. The Western imported democracy was decadence, corruption, as evident as the consumerist frenzy of the Japanese.

Death is another fixed presence in the writer’s work and life. This aspect has been well described by director Paul Schrader in the film Mishima (produced by George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, with music by Philip Glass), together with the sense of guilt, redemption, loneliness, desire for redemption. Death was closely linked to blood, to its smell, to its flow, to his films where he simulated a harakiri or had himself photographed tied to a tree, pierced, like San Sebastiano. But in his poetics of the last works, Mishima, when he concludes the tetralogy The Sea of Fertility, also represents the snow (symbol of purity) and the sea. The sea, underlines Breschi, is the metaphor of growth from childhood to adulthood, but also “metaphor of the human soul, as impetuous at dawn as it is at sunset”. In these aspects of Mishima’s narrative elements emerge that make up the unity of Mishima’s inner landscape which is often in harmony with his nature and manifestations. Mishima well represents the “enchantment in nature”.

Tradition and romanticism, two points between which Mishima fluctuated and for which he caused a scandal. His patriotism, his nationalism, his devotion to the emperor, his criticism of materialism, communism and liberalism caused a scandal. He caused a scandal mainly for his criticism of democracy, of consumer society, for the urgency of values that went beyond the simple comfortable life. A life “well lived” is difficult to live in a democratic regime, explains Breschi, because by definition it is not based on nobility of mind and a superior worldview. Life, thus, ends up being work, leisure and entertainment industry. A little bit for those who aspire to self-realization and the affirmation of higher values.

*Yukio Mishima. Enigma in five acts, by Danilo Breschi, Luni ed., pag. 256, 20.00 euros