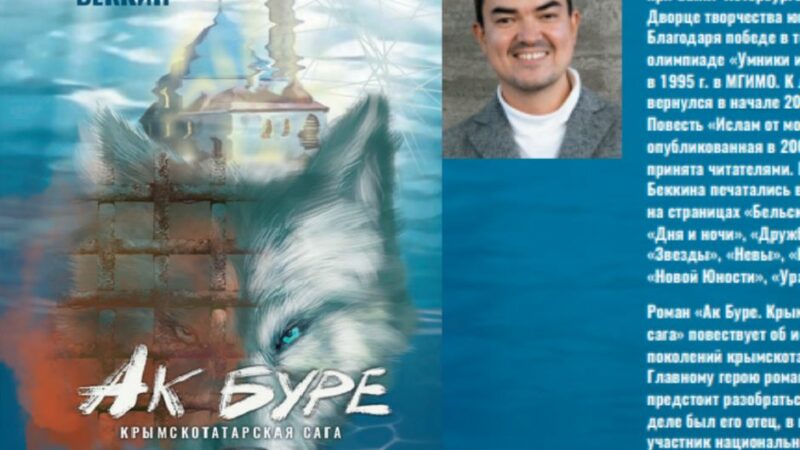

Cover of “Ak Bure. Crimeo-Tatar Saga ”, Blitz publishing house. Author Renat Bekkin

As part of the recent clash between Russia and Ukraine, i Crimean Tatars [en, come tutti i link successivi, salvo diversa indicazione] they are often ignored by the international media, as if the facts of eight years ago were completely disconnected from today’s reality.

Meanwhile, however, the Crimeo-Tatar population is not concentrated only within the Crimean peninsula, but is widespread throughout Ukraine.

The national identity of the Crimean Tatars in Ukraine is strengthening, especially in the world of cinema, as evidenced by the popularity achieved outside the borders of Ukraine by directors and actors such as Akhtem Seytablaev or Nariman Aliyev. This national identity and related movement are attracting more and more attention from researchers around the world. Global Voices interviewed Renat Bekkin, Orientalist [ru], writer [ru] And researcherauthor of literary and documentary works, of Tatar nationality, as well as author of “Hawa-la” And “Ak Bure. Crimeo-Tatar saga“ [ru]. This last book was released in 2021 [ru] on the occasion of the centenary of the birth of Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of Crimea.

Renat Bekkin spoke of the national movement of Crimean Tatars, analyzed in his book through the lens of relations between Kazan Tatars and Crimean Tatars. Correctly, Renat states that the “Tatars”And the“ Crimean Tatars ”are two different peoples, with a distinct history, destiny and culture.

Due to the many contradictions that characterize this history, Bekkin explains that he did not rely exclusively on historical sources, such as archives and memorials, but that he also addressed representatives of the Crimeo-Tatar nation, such as the veterans of the National Movement of Crimean Tatars: Ruslan Eminov, Gamer Baev, Ayder Emirov and more. Bekkin also recorded video interviews with representatives of the Crimeo-Tatar nation on the theme of its national movement [ru].

The novel “Ak Bure. Crimeo-Tatar Saga ”investigates the story of three generations of a Crimeo-Tatar family. The protagonist, Iskander (a Crimean Tatar), tries to understand whether his father, a former militant of the Crimeo-Tatar national movement, is a romantic hero or a traitor and a coward. The novel is connected to important facts in the history of Russia and Crimea.

What prompted Bekkin to carry out research on this historical issue was the discovery of how the Crimeo-Tatar history and that of the National Movement of Crimean Tatars are conceived or perceived in different ways depending on the geographical area. While in the West some know the political and historical figure of Mustafa Dzhemilev And the Mejliseast of the Ukrainian borders are better known Yuri Osmanov and the NDKT (Национальное Движение Крымских Татар – National Movement of Crimean Tatars).

Therefore, in “Ak Bure”, the author reflects on which path the Crimean Tatars should take during the Perestroika (the Eighties): the path of the NKDT, more liberal but also longer and moderate, or a more radical and decided, like the one followed in the West, through the Mejlis. The author points out that it is only the Crimean Tatars who know what is useful to the people.

Not being a Crimean Tatar himself, Renat explains that choosing a character of this nationality as the protagonist was a rather bold decision.

Renat Bekkin (RA): Normally, writers apologize for taking, for example, an Indian for the protagonist, not being an Indian, or a Negro, not being a representative of one or another people. I did not want to apologize, but still I was worried about how the representatives of the nation that I put at the head of the plot would eventually react. But despite all my fears, the Crimean Tatars received my book very warmly. They were glad that the topic was covered by a person from the outside, but they regretted that none of them [Crimean Tatars] took it on.

Renat Bekkin (RA): Normally, writers apologize when they choose, for example, an Indian as the protagonist, if they are not themselves Indians, or a black, if they do not belong to this or that other people. I didn’t want to apologize, but in any case I was worried how the representatives of the nation to which the protagonist belongs would react. Despite all my fears, however, the Crimean Tatars welcomed my book very positively. They appreciated the fact that the subject was addressed by an outside party, but according to them it is a pity that no Crimean Tatar has done so.

Bekkin notes how many Crimean Tatars often avoid digging into still open wounds. However, there are completely different conceptions between those who are in Ukraine or are originally from Ukraine in the West and those who are in the east, in the countries of the former Soviet Union.

“It is also surprising that the perception we have of Mejlis in the Crimea is completely different from that we have in the West,” said Bekkin. In many, especially among the older generations, a negative perception of Mejlis has taken root.

To understand these nuances, it is worth considering that, historically, Ukrainian national politics has not recognized their autonomy to the Crimean Tatars. The elders recall that the leaders of the former Soviet Ukraine did not allow the Crimean Tatars to return to their homeland. However, by 2014 the perception of this situation had already changed and many Crimean Tatars began to harbor ambivalent feelings towards the states, despite the crisis. In Crimea, many young people also have a negative perception of Russia.

As a result, the Crimean Tatars now find themselves between a rock and a hard place. Within Ukraine itself, the sentiments of this people have been ambiguous; there is no monolithic situation, there is no united front for “homecoming,” like the one that existed under the Soviet Union. Instead, there is a division. The Crimean Tatars who are in Ukraine and those who are in Russia occupy two worlds apart.

RA: The main protagonist of the book, Iskander, has his own path, he did not become Ukrainianized by 2014, for him the main language is Russian – after all, he lived in Tashkent since childhood, then in the 90s he studied in the international environment of the city of Kyiv. It is necessary to understand the atmosphere of Kyiv in the 90s, where, apart from Ukrainians, Russians, Jews, and Crimean Tatars lived. Indeed, the Iskander family lived for some time in the Crimea, but at that time, the main issue was survival, or the struggle for survival, the issue of self-consciousness, identity was not a priority.

RA: The novel’s protagonist, Iskander, follows his path; in 2014 he has not yet become Ukrainian and his main language is Russian. After all, he lived in Tashkent from childhood, then in the 1990s he studied in the international environment of the city of Kyiv. It is important to understand the atmosphere in Kyiv in the 1990s, where, in addition to the Ukrainians, also Russians, Jews and Crimean Tatars lived. In fact, the protagonist’s family lived for some time in the Crimea, but at the time the main problem was survival, or the struggle for survival; the issue of self-awareness and identity was not a priority.

EL: I noticed an interesting parallel between Nariman Aliev’s film “Evge (Homeward)” (2019) and your novel “Ak Bure” (2019). Crimea is described or proclaimed, albeit on rare occasions, as “Promised Land, ”As a kind of Israel for the Crimean Tatars. This was a central idea in the film, but in your novel the protagonist makes no mention of it.

RA: In my story, this comparison is rather used by the Kazan Tatar, the antagonist of Iskander – Dinar-Hazrat [an islamic honorific]. He offers an alternative to his ideological Turkic project, “Crimea is a land for the Turks, as Israel is for the Jews.” In this vein, he only argues. But one must distinguish between the Zionist project and the national movement. Nevertheless, the Zionist project was planted by force, through the purchase of land, and armed seizures, moreover, a thousand years ago, where so many peoples ceased to exist and others formed from some ethnic groups. Whereas the national movement of the Crimean Tatars (through the NDKT) saw a peaceful path, it is still the same national, people’s movement, but not through squatting.

RA: In my story, it is rather the antagonist of Iskander, the Tatar of Kazan Dinar-Hazrat who uses this comparison. [termine onorifico islamico]. The latter offers an alternative to his Turkish ideological project, “Crimea is a land for the Turks as Israel is a land for the Jews”. In this sense, his is just a polemical argument. But a distinction must be made between the Zionist project and the national movement. The Zionist project nevertheless asserted itself by force, through the purchase of land and armed confiscations, for more than a thousand years ago, when many peoples disappeared and others formed from certain ethnic groups. Although the national movement of the Crimean Tatars (through the NDKT) conceived a peaceful path, it is still the same national and popular movement, but not realized through illegal settlements.

In her novel, Renat analyzes issues that specifically concern the Crimean Tatars (or the Tatars and the Tatarstan), issues generally unknown to those who do not belong to these communities. The author presents Tatar philosophers, authors, writers and leaders, Turkish literature and Islamic spiritual rites and, at the same time, ridicules the particular characteristics of some leaders, best known to those who already know a little about their history. At the same time, Renat disseminates in the novel some magical characters who represent the powerful, as security officers and spiritual guides.

EL: Iskander (“Iskender” is also a name by which in the Turkish languages we refer to Alexander the Great) guides us through the streets of Kazan, its enchanting places, and establishes relationships with people of different religions and ethnic groups. He also guides the reader through the history of his family, through the centuries and the various places that many Crimeo-Tatar families had to visit, often involuntarily. Could you tell us about this?

I wrote for those who are interested in the path of this representative of the Crimean Tatar who ended up in Kazan, his interactions with the Kazan Tatars. I cannot avoid topics such as muftiates and succession, about another future of Russia, which is characterized by leaderism. At the same time I provided the alternative way of the future ‘development, through the history of this Crimean Tatar, when there can be miracles and life without strong leaders. Individual leaders still cannot move the block called Russia. For those who are interested in the perspective of a popular movement in the context of a national minority.

I have written for those interested in following the path of this representative of the Crimean Tatars, who found himself in Kazan, and his interactions with the Kazan Tatars. I cannot avoid addressing issues such as muftiates and succession, or another future for Russia characterized by leaderism. At the same time, I imagined an alternative direction for the future, through the story of this Crimean Tatar, a story in which miracles and life can exist in the absence of strong leaders. The leaders alone are still unable to move that bloc called Russia. [Ho scritto] for those interested in the point of view of a popular movement within a national minority.

Image courtesy of Giovana Fleck.

For more information on this topic, see our special coverage Russia invades Ukraine.

National movements of the Crimean Tatars rethought through magical realism