ROME – “Film, when it’s not documentary, is a dream, that’s why Andrej Tarkovsky is the greatest of them all». Thus spoke Ingmar Bergman, one who over the years has certainly not sent them to say against fellow filmmakers going so far as to define Orson Welles «A hoax», Jean-Luc Godard «Fucking boredom» and Michelangelo Antonioni as «Expired, suffocated by his own tedior” from The eclipse (which you can read about here) on. Not with Tarkovsky, however, who Bergman believed he had brought a new language to cinema: «Which allows him to face life as belonging, life as a dream». The feeling was mutual, to the point that, when Tarkovsky was asked to compile a list of his ten favorite films by him, he included two jewels of Bergman: one was The strawberry placethe other Winter lights. In this episode of Longform it is precisely of the latter that we will speak.

In fact, it would seem that Bergman also liked it a lot, which he came to define in an interview Winter lights as the favorite film of those he made: «I think I’ve only made one film that I really like. I’m talking about Winter Lights. Every second of this movie is exactly how I wanted it to be» and this despite the fact that – according to a large number of international critics – it is the best film slow by the Swedish author, and it’s not necessarily a bad thing after all. The reason for such a rhythmic register can be traced back, according to Bergman himself, to the difficulties in mastering the right emotions, scene by scene. In fact, it is not a work like the others Winter lights. Presented in Sweden on February 11, 1963, the film represents the central part of the so-called Religious trilogy/of the Silence of God (Like in a mirror, Winter lights, Silence).

A thematic trilogy which, moving in the same narrative terrain as The Fountain of the Virgin of 1957, maximizes the sense of bewilderment in the world before a God silentunable to provide man with the right answers to make his Faith firm (and solid), or to put it in Bergman’s words: «There are three works that deal with Reduction. As in a mirror is the conquest of the certainty of Faith, Winter Lights sees doubt creeping into that same certainty, finally Silence, with the painful acceptance of God’s Silence». A downward spiral that sees the idea of progressively abandoning God as love which provides comfort in favor of the God-spider (Anansi) or God deceiver which remains motionless before the cry of pain screamed by the man immediately muffled in the silence of the Faith.

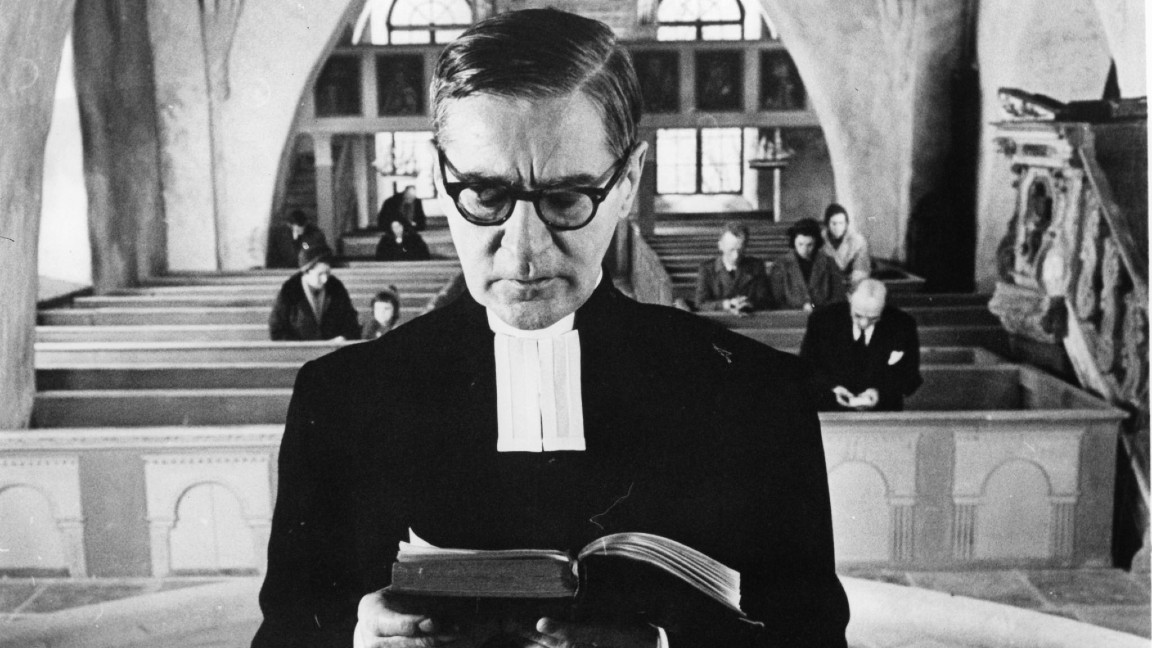

Not surprisingly, and nihilistic awareness and nullifying de Silence is emblematic in this sense (it no longer knows a remedy), Winter lights is the last work in which Bergman reflects on the existence of God and does it in the best way for compactness of narration and rigor of meditation, proposing long close-ups of such a rare intensity and essentiality as to transmit vivid anguish in the viewer, without however never allow the scenic agent – pastor Tomas Ericsson (a stratospheric Gunnar Björnstrand) tormented in spirit as well as body – to really communicate the feeling to those around him. This until the climax where a now resigned Tomas says mass in the awareness of his shaky Faith, in a ritual gesture of pure form and no conviction amplified by Bergman’s directorial choice to break its organicity through the not said (but implied) of the darkness of the end credits.

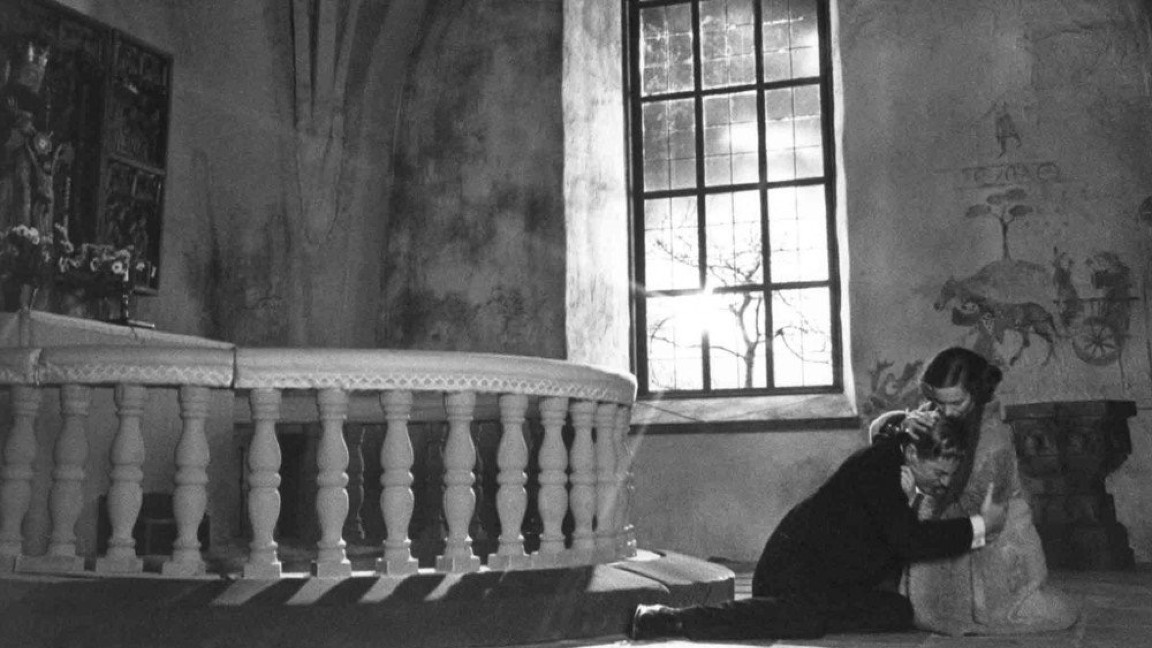

A finale of great filmic and emotional impact, undoubtedly powerful, which left its mark on the hearts of the spectators. Among them François Truffaut who saw in the climax of Winter lights a sort of metaphor – in some ways painfully current in the pandemic world – of the state of health of the cinema and the cinema: «At the end of Luci d’inverno we see a pastor who has practically lost his faith, celebrating mass in his completely empty church. The film ends there, with that priest saying mass despite everything, and I interpret that scene differently; I say to myself: Bergman wants to tell us that viewers from all over the world are abandoning the cinema, but he thinks it is still necessary to continue making films, even if there is doubt and even if there is no one in the theater».

From then on, from the climax de Winter lights and from the filmic totality of Silence – and Scenes from a wedding (which you can read about here our Longform) is perhaps the most characteristic work of this evident change of direction – Bergman’s critical spirit will go towards love and the consequences of his actions in human life. A precious work therefore, which is an evident artistic-thematic watershed of Bergman’s opus, with a decidedly curious genesis. The inspiration for Winter lights came to the Uppsala director from a conversation he had with a pastor who said he had offered spiritual advice to a fisherman who shortly after committed suicide: a fate not unlike the one Bergman designed for Max von Sydow’s Karin Persson, obsessed however by the atomic fear and by the shadow of China over the whole world (today as yesterday, incredibly).

For the making of the script – which Bergman completed on 11 August 1961 as reported by Vilgot Sjöman in the documentary Ingmar Bergman Makes a Movie on the processing of Winter lights – collaborated with his father, the minister of Church of Sweden Erik Bergman, who is said to have read the final script three times (in a row), remaining enraptured. It remains to be clarified whether the character dimension of the scenic Tomas Ericsson – what the writer Alberto Moravia enunciated as: «Pastor Ericsson never ceases to believe: the doubt that torments him concerns himself, not religion» – either directly inspired by Erik’s father-and-shepherd, or by Bergman himself (Ingmar) and his being an Ericsson/Erik-son-son of Erik. What is certain is the specific weight it has had in the history of cinema since Winter lights.

Imagined the script as chamber music in three acts inspired, loosely, by religious opera Symphony of Psalms by Igor Stravinsky from 1930, thematically twin to Robert Bresson’s 1951 masterpiece, The diary of a country curatealso on the painful and misunderstood solitude of the man of God (but with a decidedly different development), as well as a direct inspirer of his contemporaries First reformed by Paul Schraderhere to read about the debut of Blue suit) and Corpus Christi by Jan Komasa (of which you can read here our review), Winter lights it is great, very great cinema (not only) by Bergman, destined to remain forever in the memories of the time.

- Want to see the movie again? You can find it on KILOS

- OPINIONS | First Reformed, Paul Schrader and the Silence of God

- LONGFORM | Fanny and Alexander, Bergman’s last act

Below you can see the trailer of the film:

Winter Lights | the silence of God and Ingmar Bergman’s favorite film