“When I die it will be known that I have been more a writer than a photographer,” he declared in an interview Pablo Perez-Minguez (1946-2012, Madrid)—PPM as he used to sign—after receiving the National Photography Prize in 2006. Ten years after his death we know that he spoke about his diaries. “A life log”, as defined by Tono Martínez, curator of the new exhibition dedicated to the work of the one who will always be remembered as the official photographer of the Movida. The visit makes available to the public some fragments of the notebooks in which PPM wrote down—with careful clarity and precision—its wishes for the future, its intimate concerns, and also a good handful of brilliant aphorisms that, according to Martínez, “maybe one day they can be collect in one volume. It is one of the latest discoveries of a “total artist” to whom the title of Movida’s photographer it is too small for him.

James Joyce said that in his Ulises he wanted to give such a complete picture of Dublin that, if the city suddenly disappeared from the map, it could be reconstructed from his book. An analogous exercise could be achieved, in this case to reproduce the years that the The Madrid scene, from all the photographs, diaries, letters, concert tickets or postcards that Pablo Pérez-Mínguez carefully accumulated in his apartment on Monte Esquinza street; a kind of factory Warholian, in which scenes from the movie were even shot Labyrinth of Passions (1982), by Pedro Almodovar. “It’s not by chance. Pablo was very clear that he wanted to leave a mark on this world. He never threw anything away, aware that at some point someone would make use of it”, comments Rocío Pérez-Mínguez, the other curator of the show and the artist’s niece.

“And the most curious thing is that everything seemed to be already in your head before it happened,” musician Luis Gómez-Escolar Roldán tells him in a letter. There were others who photographed La Movida. Some belonged to his close circle like Ouka Leele, who studied with him at the Photocentro in Madrid, or Alberto Garcia-Alixone of the great portrait painters of his generation who, however, He refuses to be considered “the chronicler of the Movida” because he took the photographs “without documentary desire, without being aware of anything”. For Tono Martínez, it was in this aspect that Pérez-Mínguez stood out from the rest of the photographers of his time: “Pablo was the only one to have a clear awareness that the place and time we were living in was important. He was the only one who wasn’t distracted by the noise of the cannon fire on the battlefield and he was able to understand what was going on”.

“I don’t know where they’ll end up, but I’m going to photograph them all,” said the Madrid portraitist about the group of moderns who at the beginning of the eighties made a pilgrimage through places of worship such as the Rockola, El Sol or the Teatro Alfil. With that desire to document life and an explorer’s spirit, he immersed himself deeply in a world where the fundamental pattern was experimentation and, according to Tono Martínez, “no one said no to anything”. There were parties of all kinds. An extreme environment full of enthusiasm in which it was not unusual to include the price of drugs in the budget of a concert. “It was about holding out all night,” Martinez recalls. Armed with a small Canon—the camera he used to use—Pérez-Mínguez captured all he could of those human clouds of talent and infinite joy. “It was the first instagramer before Instagram and in fact I think he would be very happy to see people do now what he was already doing forty years ago: portray every moment of his life itself, ”says his niece.

The visit Pablo Perez-Minguez. Modernity and Movement of a transgressive photographer, Open until January 15 in the Exhibition Hall of the Regional Archive of Madrid, it is full of famous people. groups like Alaska and the Pegamoids, actresses like Rossy de Palma (who then worked as a waitress at the La Vía Láctea bar), the Ruiz de la Prada sisters, and of course, the film director Pedro Almodóvar, who stars in one of the sections of the exhibition. One of the most repeated faces is that of Javier Furia, the first singer of Radio Futura, who was a partner of Pérez-Mínguez for a few years. “My uncle was late in love,” says her niece. “His first relationship was with a woman, Paz Muro, although shortly after he met Furia, with whom he had the most important romantic relationship of her life.” A courtship that never materialized due to the somewhat complicated personality of the photographer. “He was a person who was very jealous of his intimacy and had deep-rooted customs that made life as a couple difficult,” he explains. Tono Martínez also remembers that in those years it was not usual to have a serious relationship, with a traditional scheme. “That was just cool,” he says with a laugh.

ANYTHING GOES

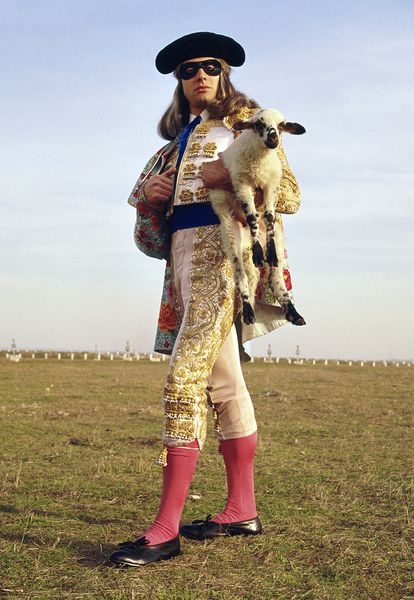

Pérez-Mínguez’s work was a challenge to conventions. In one of the notes that we can read in his diaries, he writes: “Anything goes: in the right place, at the right time, in the right dose.” It is an extension of the famous VALE TODO, the leitmotiv that propelled through new lens, the magazine that he directed together with Carlos Serrano, and that was an emblem of the avant-garde and photographic experimentation during the seventies. One of his first acts of insurrection against the artistic tradition inherited from Francoism was to take his friend, the philosopher Ignacio Gomez de Liaño, to a vacant lot in Barajas, to dress him in a bullfighter’s suit, put a wig and a mask on him, and make him hold a lamb in his arms. Photography, one of the most iconic of his entire career, already indirectly announced some of the features that would define his work: conceptualism, experimentation and constant transgression.

On another page of his notebooks you can read: “God constantly fills me with Faith so that I can continue fighting against the tide, with the invisible light and the almost blinding power of knowing that everything is going well and that the ship reaches a safe port.” It is not the only religious reference that appears in his annotations or in his work. Pérez-Mínguez’s photographs have a mystical flight as a result of his interest in sacred images, “and the great spiritual background”, which according to Martínez, also reflected in his personal life. “He was not a believer in the traditional sense of the word. Pablo’s spirituality was postmodern, pop, kitsch, cañí,” he comments. His niece, who only knew him in the last three years of her life after contacting him through a Facebook message, remembers how her uncle once used to say: “But how do you expect God to come down and tell you? He will have to tell you with signs.”

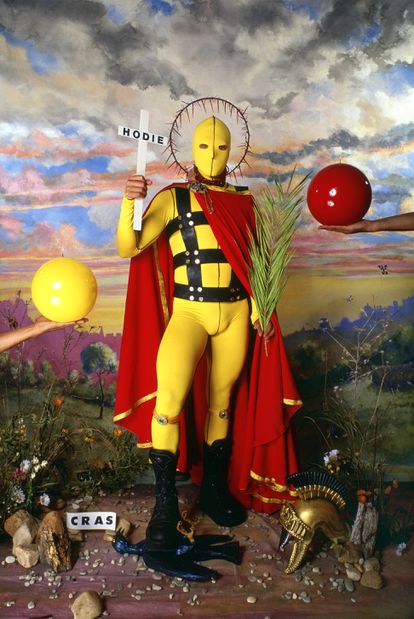

And one of these messages from God fell on him in the form of rain while he was walking around Lisbon. He took refuge inside a church and inside a chapel he found the figure of San Expedito, a saint of Armenian origin and highly venerated in Brazil, dressed in armor and a Roman tunic, and who in his right arm held a sign with a text on which the word was written hodie, What does it mean today. In 1990, Pérez-Mínguez had added the phototext technique to his portrait style. With her, she incorporated a poster with a message held by the characters in her portraits, to help the viewer interpret the photograph. One of the most popular examples appears on the album cover Physics and chemistry of Joaquin Sabina. Pérez-Mínguez fell in love with the figure of this saint and dedicated an entire series to him, which has its own space in the exhibition. Gómez-Liaño wrote an article in which he analyzed this obsession of the Madrid photographer: “What San Expedito revealed to the photographer from his Lisbon chapel was the transcendental value of icon that PPM seeks in his photographs. It is something that is clearly seen in the long list of “celebrities” of the pop world and of artistic culture that PPM has iconized when it seemed that it was only photographing them.

His place of work and residence located on Monte Esquinza Street is a fundamental part of the artist’s personal mythology. “His study of him was a kind of Freudian cabinet in which he was able to capture the psychology of the characters he portrayed,” comments Tono Martínez. Pérez-Mínguez had a special ability to connect with the people he photographed. According to his niece, the artist himself even commented that his favorite moment was when he “deflowered the character in the first session.” He assures that with the camera in his hands he had the power to “fool and hypnotize the character”. It was Ouka Leele herself who described PPM’s photography “as an act of love”. “Something that sometimes took place literally,” comments Tono Martínez with a laugh.

One of the pages of one of the notebooks exhibited during the visit is headed with the following title: Autobiographical book prologue. A little further down, in an entry dated July 20, 2010, it reads: “I have the brilliant idea of asking Rocío PM (her niece) to help me make this book: at the level (superficial or deep… . always intense) that she is most interested in (that we are most interested in)”. A message that she read after her death and that ten years has culminated in a biography that La Fábrica will publish on November 25. “She worried about leaving traces so that someone in the future would write about her life,” adds Rocío Pérez-Mínguez or RPM, which is the formula that she used to introduce herself to her uncle in that message that I sent her. By facebook.

You can follow ICON at Facebook, Twitter, Instagramor subscribe here to the newsletter.

The obsession to leave a mark of Pablo Pérez-Mínguez, “the first instagramer in Spain”