Crossing the arm of the sea that separates the continent from the emblematic island of the Var coast, one wonders what fly could have bitten Alain Damasio to make it the scene of a Homeric battle, a prelude to a future revolution in his novel “Les Stealthy”. What if that was the spirit of the jazz festival that has been taking place there for 21 years? We know the commitments in favor of the all-round emancipation of its president and founder Franck Cassenti, and, somewhere, this humanism vibrates as soon as we meet the first members of the team, in this case the volunteers who are waiting spectators on the continent. These positive vibes are obviously the result of demanding and sensitive programming. In addition, this year, the concerts once again took place in the courtyard of Fort Sainte-Agathe, a venerable defensive bastion whose walls have something of a spirit of resistance.

- Leloil Brass Band (Aucepika photographer)

On the port of the island, in the streets of the village and on the steep path that leads to the Fort, brass bands line the paths of the public. We particularly enjoy an ensemble led by the Marseilles trumpeter Christophe Leloil.

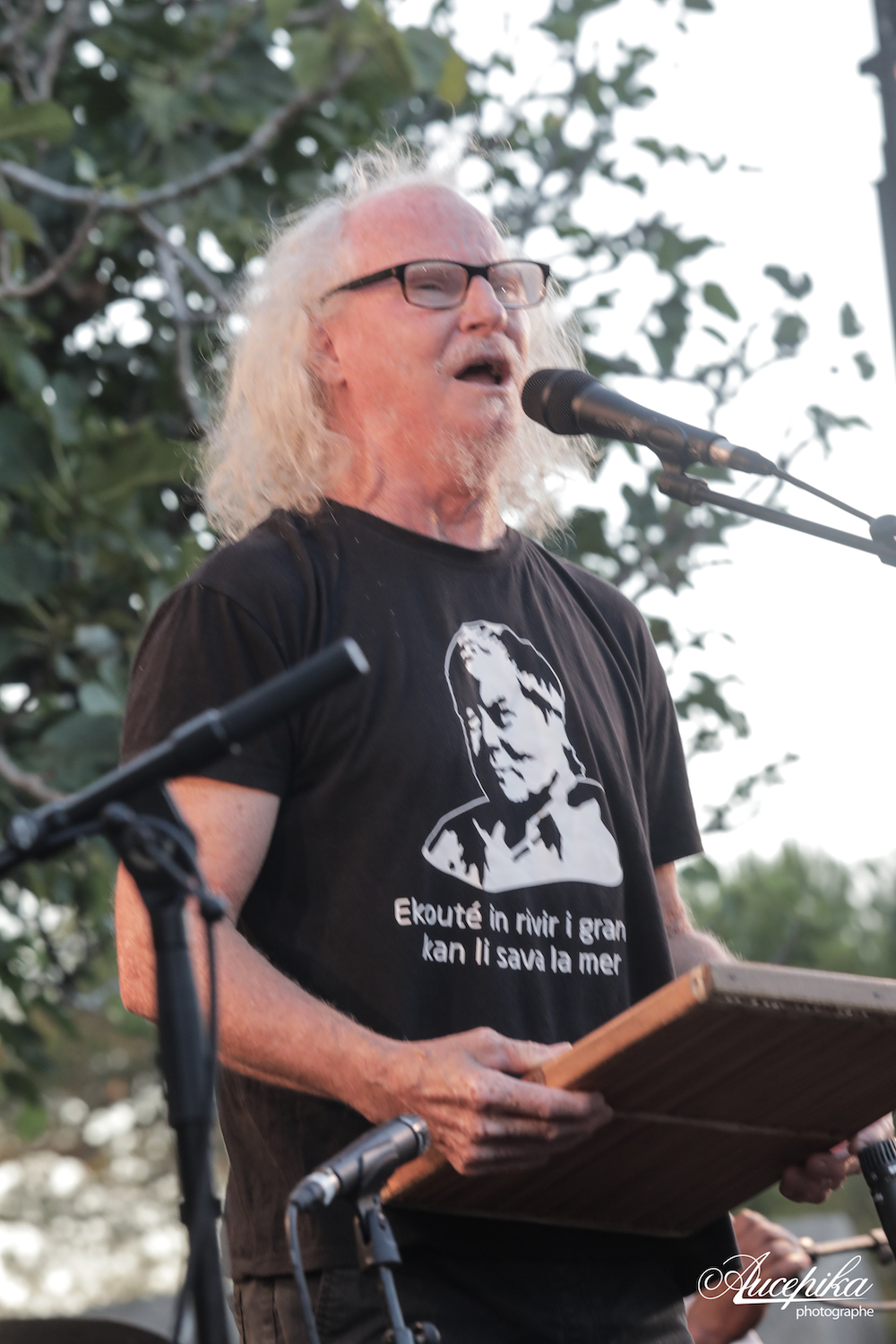

- Danyel Waro (Aucepika Photographer)

July 11: Reunion is here!

Daniel Waro and his tour friends take over the stage with their percussion and just a bass ukulele for a big hour of maloya. With his head voice and his force of poetic conviction, the eminent Reunionese puts himself completely at the service of a repertoire forged by centuries of Creole resistance. It should be remembered that the maloya and its instruments, such as the “cayamb” and the “roulèr”, were prohibited until 1980 because they came from maroonage, the struggle of slaves to escape the hell of the plantations. The singer, son of a family of white proletarians, has never ceased to restore his letters of nobility to these songs of liberation, sending back to the “zorèys” and the powerful white families of the island a message of dignity from the island lowlands. Creole proletarians of all countries, unite. The emotion is there, even in some quite delicious ribald inclination. Because for Waro and his musicians, there can be no resistance without sensuality. Unable to remain seated, of course.

In the second part of the evening – in Porquerolles, the order of scenic priorities seems reversed, as if the hierarchy in the show had been abolished -, place for the group An’Pagai, a group of young musicians from the Mascarene archipelago, representing the new generation of maloya. More electricity then, with electric bass player, DJ-saxophonist, two drums, two choristers and a singer.

- Damien Varaillon (Aucepika photographer)

July 12: two flautists and a bass player

That evening is the party for Damien Varaillon. Very present on the stages of French contemporary jazz, it is up to him to officiate on the double bass for Naissam Jalal then for Magic Malik.

From the first piece with the Franco-Syrian flautist, we understand that – to use the slogan of the AJMI of Avignon – the best way to listen to jazz is to see it. Attending a concert by the “Rhythms of Resistance” quintet makes it possible to perceive the emotional waves that emanate from a music whose obviousness disputes it with the requirement. Far from Orientalism in the repertoire from their latest album. There, it is rather towards the West that the group is eyeing, with its borrowings from the Andalusian intangible heritage, in particular from the bulería and the samaï, of which the flautist will not fail to recall that it comes from a medieval Muslim civilization. of an extreme artistic refinement, and humanist before the hour. In fact, the pieces from the disc Another world have this architectural lightness of the chiselled ceilings of the Alhambra in Granada.

They also have very contemporary resonances borrowing from the paths of a futuristic groove, without ignoring the accents of a universal blues which points the tip of its nose when the conductor lets go, notably by singing into her instrument. Arnaud Dolmenflamboyant on the drums, unfolds beats who interfere in the compositions with a thousand and one nuances, without renouncing any nods to his gwo-ka heritage. On tenor and soprano saxophones, Mehdi Chaib deploys spiritual volutes that a Yusef Lateef would not have disdained and we say to ourselves that it is a pity that he does not express himself more in the world of jazz. His counterpoints to the remarks of the flautist/singer are masterful in every way and his choruses overflow with a sharp poetic sense.

We could make the same remark with regard to the guitarist/cellist Karsten Hochapfel, overflowing with generosity. As for the double bass player, Damien Varaillon, he carries the overall structure with benevolent solidity and conviction, endowed with an unparalleled sense of rhythmic and melodic nuance. We also salute the explicit environmentalist and anti-racist convictions of Naïssam Jalal. She will not hesitate to declaim her poem “Besides we are from here”, an ode to the reception of the Other in a hexagon which turns its back on a large part of its youth that some would like to see excluded because of its presumed origins.

Come on, jazzmen and jazzwomen of our “dear and old country”, take example from the poetic courage of this flamboyant musician and come out of your too often hypocritical silence in the face of ambient racism!

- Maxime Sanchez, Magic Malik (Aucepika Photographer)

Then place the quintet jazz association, led by the flautist Magic Malik – of which Jalal will point out what she owes him. Damien Varaillon (“the flautists’ favorite bass player”, as she would say) melts with delight into the “Coltranian” repertoire of a musician whose unprecedented experiments have dotted the soundscape of the last twenty years. There, on the other hand, place for a more conventional jazz. The leader reveals to the public that, when he heard Coltrane, he had the feeling of an echo of his Guadeloupean musical heritage.

He thanks the trumpeter Olivier Laisney for providing him with a “turnkey” group to explore this dimension of his sensitivity. The flute/trumpet combination resonates with feigned fragility, while the rhythm unfolds a deep and nuanced swing (beautiful piano axis Maxim Sanchez / battery Stefano Lucchini), at the service of a discourse whose spirituality unfolds in Malik’s vocal psalmodies, but also in sequences eyeing collective improvisation.

- Jason Moran & Archie Shepp (Aucepika photographer)

July 13: Myths and Dreams

The Godfather is in place. Archie Sheppwhich every year returns to the island as a symbol of the festival’s emancipatory program. Franck Cassenti never tires of recounting the circumstances of their meeting when, forty years earlier, he met the saxophonist in Paris and had the impression of seeing a character from a Cassavetes film. He tells her about a film project on jazz and his wish to include her in it. To which Shepp replies that, although he does not like the word “jazz”, because born in the brothels of New Orleans, he loves cinema and wants to make a film with him…

The pianist jason moran accompanies him on stage, helps him to sit down and presents him with his tenor saxophone. Moving entry on stage of an Elder helped by a forty-year-old.

After having moistened his beak, the first notes of “Wise One” fly from his instrument. It’s that, tonight, the duo is there for a live delivery of the disc Let My People Goon which intertwine spirituals and tributes to Coltrane, Monk and Ellington. From the outset, Moran explores improbable tempos that allow his playmate to embark on the quest for the ideal, unattainable note. Come in then Michael Benitaon double bass, on “Another Rendez-vous”, interpreted rubato, propelling musicians and audience out of time with a repeated central arpeggio. The now trio embarks on a very sensual interpretation of “Ain’t Misbehavin'”. Shepp simpers when he sings “I didn’t behave badly, I kept all my love for you” on this mythical anatole. On “Lush Life”, composed by Billy Strayhorn, her singing takes on fragile and strong accents which are reminiscent of the cracks of that of a Billie Holiday, while evoking some accents of cante jondo flamenco. Moran quotes “Well You Needn’t” by Monk in the course of his solo, a way of reminding us that the repertoire they take on is jazz in a form of totality.

This libidinous music languidly teams up with the following theme. In fact, on “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child”, spiritual (and not gospel), we have the feeling that Shepp is projecting intimate parts of his autobiography, as if he were preaching his condition as an artist, an eternal blues boy “ true believer away from home”. The sun sets. The announced supermoon darts its tender orange glow on the scene. Clearly, even the stars are with them, with us. On “Ballad for a Child”, from the album Attica Blues and composed for Carl Massey’s child, the musician whispers “All the world needs is a baby’s smile”.

- (lr): Jason Moran, Archie Shepp, Michel Bénita, Olivier Miconi (Aucepika photographer)

On “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore”, old Ellingtonian saw, place to the young trumpeter Olivier Miconi, for a soulful solo – he had previously led his own brass band backstage to deliver a moving serenade to his mentor. Finally, Moses is summoned at the end of the set. On “Go Down Moses”, Jason Moran plays Arabic notes, summoning the universality of a song that would resonate with the Arab Spring. On the saxophone, Archie Shepp seems in a trance as his vibrato is intense. The assistance and the musicians are traversed by the same shiver. Tears are flowing, both in the audience and in the eyes of the boss. A too rare moment of communion, sensual and spiritual, which exposes the emotions. “Let my people go”…

It was not easy then for Franck Cassenti to go on stage to read, seated in an armchair, the short story “Novecento, the legend of the pianist on the ocean”, by Alessandro Baricco. Nevertheless, accompanied by the pianist Jacky Terrasson and by Michel Benita on double bass, he easily frees himself from the constraints of public reading and becomes a mischievous storyteller.

The scene of the imaginary challenge between the self-proclaimed “king of jazz” Jelly Roll Morton and the hero, whose first name was given to him by his adoptive father, a sailor from the liner on which he was born when the previous century was born, takes life before our eyes. This moving visualization is the art of storytelling. And when the stage “Porquerolles” (pronounced “Powquewol”) is added to the original text, we say to ourselves that if we are in good port, the boat of eternal jazz which transports Novecento, will never be able to stop. …