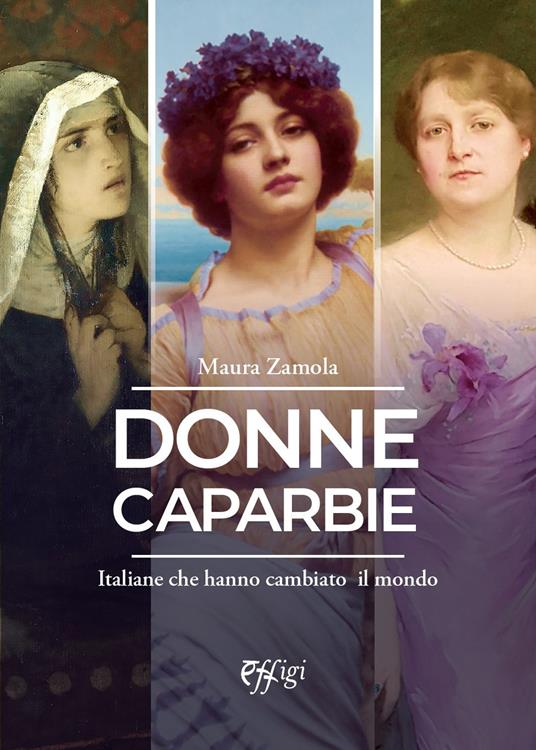

Maura Zamola, a degree in literature, a teacher in middle and high schools, a past as a feminist from the 1970s onwards, has been passionately practicing the profession of tourist guide in Umbria and Tuscia for many years. These experiences of hers have now merged into the book “Women stubborn. Italian women who changed the world ”, Effigi 2022, in which she focuses on significant personalities of women in an excursus that ranges from the Etruscan age to the early twentieth century. More or less well-known historical figures are rediscovered and brought to attention, whose events, although sometimes with international implications, took place in the territory of central Italy, mainly between Umbria and Lazio, a circumstance that gave the author the opportunity to also offer the reader valuable information for tourist visits in those territories.

The characters that Maura Zamola has chosen come from different social backgrounds, they are noble or common people, bourgeois or saints, but all are united by the strong will not to bend to the destiny that the law of patriarchy has already decided for them, whether it is marriage maternity or nun. They will have to fight, find roundabout ways, they will act in different ways: some by working with cunning, some by irreducibly opposing patriarchal power, some by acting as a protagonist, some by making themselves an instrument to condition male power, sometimes even using deception and violence , arriving at unforeseen outcomes and highlighting new possibilities and different ways for women’s lives.

The first figure the author presents to us is Tanaquil, an aristocrat from Tarquinia, who lived between the 7th and 6th centuries. BC, who had married Lucumone, son of an Etruscan noblewoman and a Greek exile from Corinth, heir to a substantial patrimony. Tanaquil, whose story has come down to us through the story of Tito Livio, will be able to convince her husband to leave the provincial Tarquinia for Rome, which she would have offered her husband greater

chance to emerge. She will know how to use the art of divination to interpret prodigies, she will be able to weave a network of acquaintances and alliances in Rome to put her husband in a good light and it will be she, thanks to her undoubted political skills, who will create two kings: her husband will in fact succeed Anco Marzio with the name of Tarquinio Prisco and the son-in-law Servio Tullio, who she had considered more able than her own son, will succeed Tarquinio. “In ancient matriarchal societies – underlines Maura Zamola – to become king or leader, one needed the investiture by a high priestess, considered the earthly representative of the Goddess. Here, even in the Etruscan age, something of the ancient custom remained”. It is precisely the figure of Tanaquil that allows the author to illustrate the transition from matriarchal to patriarchal civilizations and to introduce the difference between Etruscan and Roman women. In Europe it was the migratory waves of the Kurgan or Indo-Europeans that determined the end of the matriarchal civilizations, but traces remain in subsequent civilizations and one of these, in which ancient traditions are still found, was precisely the Etruscan one.

Zamola outlines in two interesting chapters, albeit necessarily in a synthetic way, the condition of Roman women, a condition whose premise is significantly found in the act of violence committed by the Romans towards the Sabine women, through whose kidnapping the female population of the newly founded city. All the misogynistic and patriarchal treatment of the Romans towards women descends from this story, a mentality that informed Roman law, which then spread to all the conquered countries, establishing itself even if previously these countries had other uses towards women. You have to get to

1st century BC and the Imperial era to see some changes in the status of Roman women. Zamola outlines the figure of Livia Drusilla, wife of Octavian Augustus, who he defines as the first first lady of the Roman world. Her intervention in the politics of the empire will be remarkable, but she will be able to remain in the shadows and implement the change within the conditions then in force, unlike Giulia, daughter of the emperor who, opposing as a rebel, met a bad end.

Amalasunta, daughter of Theodoric, king of the Goths, found herself carrying out the function of regent of the younger son Atalaric, the designated heir of the deceased king. Amalasunta, like Livia, was not satisfied with the role that patriarchal society assigned to women, she wanted to govern. She failed in her attempt to consolidate her position by trying to marry the emperor Justinian, because she found another headstrong woman in her way: Theodora of Byzantium. In order to manage the power she tried all possible ways, but she found herself in a very disadvantaged position and not even using male methods, resorting to cunning and murder was enough. She was eventually overwhelmed and legends of her captivity and tragic death still flourish on the shores of Lake Bolsena. Another woman around whom myths have been built making her a legendary character is Matilde di Canossa, who found herself at the center of complex historical events in the investiture controversy between the Empire and the Papacy. She was a woman of great power, who knew how to hold with a firm hand a large territory in central Italy which had great strategic value; she knew how to govern with wisdom and generosity. She showed herself to be a skilled politician and, if necessary, a warrior at the helm of her troops. She too was inspired by a strong ideal of reform of the Church, which she never failed.

The central part of the book is dedicated to the Mystics and after a general introduction of the period between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries, the author outlines the profiles of Chiara d’Assisi, Angelina da Montegiove, Rita da Cascia, Lucia Broccadelli, all of umbrian. At the beginning of the 13th century new needs for spirituality arose, of which St. Francis of Assisi was the protagonist; thus arose a new popular religious movement in which many women took part. The phenomenon of voluntary urban imprisonment spread in a room of their house or in a small house near a church or a convent: they were single young people who refused marriage arranged by their families and preferred virginity or even widows who did not intend to experience the marriage. In central and northern Italy and in northern Europe, the movements of the beguines arose, also called penitents, humiliated, clothed, etc. Another significant phenomenon was that of female mysticism “By claiming that God, the Virgin or some Saint had appeared to them asking to divulge certain requests or advice, they could get around the prohibition of speaking imposed on women by the Fathers of the Church and ecclesiastics since the time of Saint Paul . So they took each other

the authorization to preach and to make their voices heard, covered by an authority that no one could question.” Among the Umbrian mystics, the figure of Clare of Assisi shines out and her strenuous struggle with the ecclesiastical hierarchies against the prohibition of speech and to make spiritual dialogue and preaching particular points of her community. You fought against the granting of rents by the Papacy to maintain the “Privilege of Poverty” and managed to impose your own Rulewho called “Form of Life of the Order of Poor Sisters”, which was more democratic than the men’s one and expected all decisions to be taken unanimously. Another fighter was Angelina di Montegiove who managed to create the Third Order of Observance, a community of tertiaries at the convent of S. Anna in Foligno, who dedicated part of their time to prayer and meditation and part to assistance and education of girls. Unfortunately, with the Council of Trent, strict enclosure was imposed on all female communities, both monastic and of the Third Order, and it was no longer possible for any of them to lead an active life of apostolate, assistance and education.

Inserted in very complex family and historical events, in an era of violence and maximum corruption of the papacy, the lives of Giulia Farnese and Lucrezia Borgia take place, around which even great intellectuals of the time did not hesitate to spread gossip and misogynistic images. The author does not hesitate to delve into their lives, not denying weaknesses and connivance with the crimes of their families, but manages to highlight how, when life has offered them the opportunity, they have been able to demonstrate political and even entrepreneurial skills in favor of the subjects of their possessions, also trying to find comfort in an approach to faith to face the last hard trials of life. The search for an entirely interior religiosity and a profound spirituality in the context of struggles within the Church led the poet Vittoria Colonna, a friend of Michelangelo, to find refuge in Orvieto in the convent of S. Paolo and then in that of S. Caterina in Viterbo . Here she had relations with the “Ecclesia Viterbensis” group, open to dialogue with Protestants. Only an early death probably saved her from the rigors of the Roman Inquisition.

Extraordinary figure of unscrupulous rebel, accumulator of wealth, skilled businessman, politician and manipulator of conclaves was Olimpia Maildachini, the popess, who knew how to play with the cards that the time and the circumstances offered her. A woman could not reach the peaks of power in the Church, but it was she who created the fortune of her brother-in-law Giovanni Battista Pamphili who led him to the papal throne in 1644 with the name of Innocent X. The book closes with the figure of an extraordinary businesswoman of the early twentieth century, full of imagination and resources. Of humble origins Luisa Spagnoli from a small grocery store was able to create a thriving confectionery industry in Perugia. She later established a collaboration with the Buitonis that brought their company to the peak of success with the production of chocolate, up to the invention of the Perugina baci and other lucky products still consumed today. From one of her intuitions, her children later created the famous fashion brand that bears her name. With her activity “she anticipated the introduction of women into Italian industrial work by half a century”, recognizing them a salary not inferior to men and maternity leave paid ahead of its time.

These “stubborn women” can be talked about and discussed together with the author Maura Zamola on Thursday 26 January in the Reception Room of the New Luigi Fumi Library from 17.00 to 19.00, in a meeting organized by Filo di Eloisa. Eloisa Manciati cultural association, of Fidapa BPW Italy of Orvieto, of the New Luigi Fumi Library and with the patronage of the Municipality of Orvieto.

Subscribe to the Article21 Newsletter

The stubborn women of Maura Zamola who fought against the patriarchy – Article21