It is in the poverty of the hermitages, in the lost sanctuaries in the depths of the mountains, at the foot of an oak tree or a Calvary, that the voice of silence is heard which speaks to faith. One wonders if it is the mountain that gave birth to Maronite spirituality or if the latter sought Lebanon to come and flourish there.

Listen to the article

For Easter this year, a mass was celebrated on the edge of a rocky precipice, in the heart of a steep valley. No decor or liturgical installation. Only a priest standing at the end of a rocky blade that cuts through the void and on which the faithful parade. The scene seems unusual, original and unprecedented. However, the priest only perpetuates a tradition which goes back to Saint-Jean Maron.

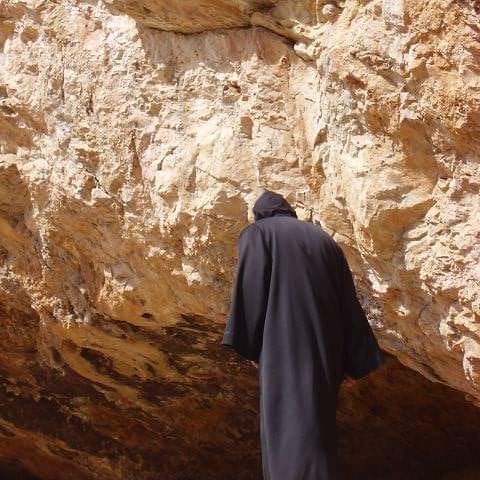

Men and women advanced on improbable paths, bold and out of nowhere, redrawing the contours of the ravines and the abyss. On both sides, the perforated walls of the mountains rise to merge with the forests, the mists and the clouds. The scene appears complete, requiring no intervention. For the Maronite tradition, this is its architecture par excellence. In its verticality, its light and its depth, it is the work of the divine as translated into its spirituality.

The valley

It is an acheiropoietic architecture (not made by human hands) which found its full vocation in its encounter with a monastic church inclined to asceticism. For the French ambassador, René Ristelhueber, “monasticism, already very much in favor in the plains of Antioch, has taken on an even greater extension in Lebanon”.

The valley then constitutes a manifesto of architecture. It takes shape and sets itself up as a sanctuary where the natural and the built mingle. Alphonse de Lamartine finds there the principles and details of the cathedral. “The whole Valley of the Saints, he wrote then on the Qadisha, resembles a vast natural nave of which the sky is the dome, the crests of Lebanon, the pillars, and the innumerable cells of the hermits dug into the sides of the rock, the chapels.” This spectacle is still complete for him in the valley of Hamména which today bears his name. He is captivated by the surrounding falling waters whose noise is similar, he notes, “to that of the organ pipes in a cathedral”. What the locals felt in their religious soul, the travelers expressed.

Far from the great monuments of Christianity, it is in chapels and oratories that meditation flourishes. It is in the poverty of the hermitage of Anneya, in the sanctuaries lost in the depths of the mountains, at the foot of an oak or a Calvary, that the voice of silence is heard which speaks to faith. It is in the brutality of the poverty of Notre-Dame-d’Ilige that Father Michel Hayek expresses the power of his faith. “Here, we can only pray in Syriac, he confides, the language of hostage souls, the language that whispers to compassion, the language of repentance and tears.”

The holy and the sacred

One wonders if it is the mountain that gave birth to Maronite spirituality or if the latter sought Lebanon to come and flourish there. The smallest wall is hollowed out to shelter a convent, a solitude, an oratory, a hermitage. Nature in the wildest state receives here and there, to quote Lamartine, “a few solitary figures circulating among the rocks and shrubs, working, reading or praying”.

The mountain embodies, so to speak, the concept of the saint, well beyond the sacred which, according to Martin Heidegger, remains specific to the temple-cathedral in its immutable reading of the world. Holiness transcends the sacred. “Jesus linked the vigil to prayer in the solitude of the mountains, the desert, the cell, as if there is no prayer without vigil, without mountains and without cells”, writes the Maronite bishop Simon Atallah.

This mountain seems to be the place of reception par excellence. With its humble chapels, its philoxenia contrasts with the church-museum which, for the philosopher Philippe Sers, sinks into self-satisfaction like “a cemetery of personal admiration”. Where the latter tries to read the world, the mountain seeks transfiguration. By its immensity and its cavities, it shelters the work, the day before and the prayer.

The travellers

This mountain deeply marked the travelers of the XVIIᵉ century. Among these, the knight Laurent d’Arvieux lingered over its numerous caves and its anchorites. Father Eugène Roger also evokes these monasteries which “are in deserted places, in rough rocks, where it seems that nature has pleased to make these solitary, grotesque, and penitent places”, he writes.

In the XXᵉ century still, Maurice Dunant speaks of these convents “half hollowed out in the rock” and which he describes as being “clinging to the most inaccessible walls”. Nature is sculpted and metamorphosed, reproducing the elements of architecture. “As soon as one enters the Syriac interior of the country, writes Father Jean-Maurice Fiey again, one finds the rocks of the hills pierced with caves and the paths marked out with monastic sanctuaries.”

Terror and dread

This nature disturbs, upsets and challenges. It is the idea of terror and dread that the pens of the pilgrims constantly transcribe. At the beginning of the 19th century, Louis-François Cassas noted this disturbing feeling caused by the spectacle of the Qadicha. “Pleasure is mixed with terror, he exclaims, both are brought to the highest degree.” He immediately describes this enormous rock which, soaring above the stage, will merge with the clouds. “Everything frightens the soul and disturbs the mind,” he adds. A century later, René Ristelhueber still insists on this “grand, sometimes terrible beauty of certain Lebanese sites”.

This paradoxical aesthetic, so conducive to contemplation, to meditation, and which seems to lend itself to Maronite spirituality, emanates from a principle of interiority. It proceeds from subjectivity and makes ethics prevail over aesthetics. The sentimental subjectivity that it implies allows an amplified reading of the world. The peaks seem higher and the valleys deeper. The dimensions are dramatized and the time exaggerated. Retreats and chapels abandon themselves to another age and to what Immanuel Kant designates as absolute grandeur, freed from all reason or logic, devoting itself only to the sentimental and the spiritual.

We are in the presence of a magnitude that is neither measurable nor comprehensible. It is felt, not understood. It is immaterial, without scale and without unity. It “is equal only to itself”, writes Kant, who defines this absolute greatness as “that which is great beyond all comparison”.

The beautiful and the sublime

This experience of the mountains, mixing the terrible with the pleasant and grafting the spiritual to the natural, engages interiority, and therefore subjectivity, towards the discovery of an aesthetic that does violence to reason. Kant calls this the sublime and defines it as that which elevates the forces of the soul above the ordinary. It is not comparable to the beautiful. It is not of the same order. Because “for the beautiful in nature, writes Kant, we must seek a principle outside of us, for the sublime, only in us”. The sublime is no longer, so to speak, anything but a projection of oneself, of one’s interiority, onto the spectacle that presents itself.

For Kant, the beautiful charm, while the sublime moves. If the beautiful pleases by the consideration of the senses, the sublime, Kant tells us again, pleases him by his opposition to the interests of the senses. This is undoubtedly what generates the feeling of terror and embarrassment. We are witnessing, faced with a sublime spectacle, a collapse of aesthetic conventions. The sublime is therefore noble, magnificent and terrible at the same time. The satisfaction it inspires is mixed with horror and does violence to the understanding. In his Aesthetic judgment, Kant writes: “The day is beautiful, the night is sublime.” Thus the sun is beautiful, the violence of the storm is sublime, and a monument is beautiful… the mountain is sublime.