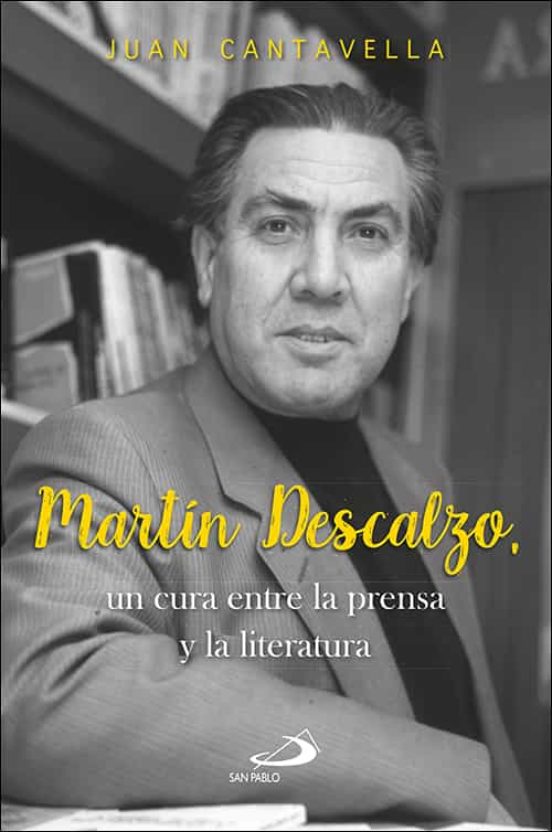

The retired professor of the CEU San Pablo University, Juan Cantavella, has just published this kind of biography of José Luis Martín Descalzo, journalist and priest, visible head of a generation of journalists and priests who marked the conscience of Spanish Catholicism in the 20th century. A biography that is something more than a biography since it synthesizes, and reproduces by way of example, perhaps a sample of the most outstanding texts of the man who was, among others, the Nadal winner of literature.

The author of this work confesses, at the end of the introduction, what he intends: “We would like nothing more than to awaken in each other the need to approach his writings to get the most out of so many pages that came out of his machine. They would all check that strength of your arguments He knew how to add the softness of emotions to form with it a set that hardly left anyone indifferent”.

Priestly profile of Martín Descalzo

There are many aspects that deserve to be highlighted in this work that undoubtedly contains many hours in the kitchen of reading and writing. The first of these is the insistence on priestly profile of Martín Descalzo that gives meaning to all his performance, all his work. It is not just about approaching the figure of an outstanding journalist in the history of journalism, nor of a writer more than laureate. It is a form of exercise of the ministry, what the classics of priestly spirituality called “the apostolate of the pen”. Hence the extensive presence of priests in his novelistic work, from “The border of God” to the more explicit “A priest confesses.”

This priestly perspective that permeates his writings did not turn Martín Descalzo into a solipsistic exponent of the usual clericalism. In fact, his novels, which have gone too unnoticed, are full of secular spirit. That is to say, of a conception of the world as the place of the effective and operative presence of the Christian. It is very laudable that it is recalled, at this time, the denounces that Martín Descalzo made of “bourgeois Christianity” or gentrified. Or the freedom with which he wrote, which could also be called, in a theological way, “parrhesia”.

catholic novel

This book also raises the issue of the Catholic novel, the thesis novel, or Catholic novelistics. Martín Descalzo confessed, on several occasions, that his work would not be understood without Bernanos. It could be said that his trail falls within that great literature written by authors such as Francois Mauriac, Graham Greene, Julien Green, Evelyn Waugh, Bruce Marshall, Gertrude von Le Fort, Maxence van der Meersch, among others.

A significant fact of the work of Martín Descalzo in his poetic vein, which also links him to a generation that, to a great extent, became known with the magazine “Estría”. There we find names such as Servando Montaña, Luis Peralta, Ricardo García Villoslada, Joaquín L. Ortega, Florencio Martínez Ruiz, Valentín Arteaga, Juan Bautista Beltrán, Jesús Tomé, Manuel Carrión, Víctor Manuel Arbeloa, Jesús Manleón, Carlos de la Rica, Manuel Avezuela, José María Javierre, José María Cabodevilla or Luis Alonso Schöekel.

journalistic profile

Finally, leaving evidence of his role as a playwright, we must address journalistic profile by Martin Barefoot. His career, from the times of “El Norte de Castilla”, or his time as a conciliar chronicler in “La Gaceta del Norte” until he reached “ABC”, with “Blanco y Negro” or the time in “Vida Nueva” or the religion section in the newspaper of Prensa Española, passing through his program on Televisión Española or his collaborations for newspapers and magazines in Latin America.

In this sense, one could say, well, it has been said, that Martín Descalzo was “a chair of religious journalism”. His name is linked to a generation that existed, that no longer exists, and I don’t know if it has left a legacy. These are names like Lamberto de Echeverría, Ramón Cunill, Jesús Iribarren, Antonio Montero, José María Javierre, Joaquín Luis Ortega, Bernardino M. Hernando, Antonio Pelayo, Pedro Miguel Lamet, Norberto Alcover, José Antonio Carro Celada and Miguel de Santiago, among others.

In fact, Juan Cantavella, points out in this regard that “as we approach the present moment, the position of the Church as an object of journalistic interest has been weakening, but that eagerness that was lived in the second half of the 20th century was seen reflected in those who have become growers of that plot. Few were at first the laity who entered this area, but later they already occupied preponderant positions and have known how to dignify it”.

Religious information in contemporary Spain

We must thank Professor Cantavella for bringing us the memory of a priest, journalist and writer, without whom religious information in contemporary Spain would not be understood. Perhaps some bibliography on that period is missing. And having delved into some aspects of the life of Martín Descalzo, for example and among others, his relationship with the ecclesiastical hierarchy of his time.

Cantavella tells that some bishops asked him to write a work on the problems of the Church, by way of his “Dialogues of Passion”. The progression of his disease prevented him. Shortly before he died, he explained to his disciple Santiago Martín: “Those of us who love the Church have to go out and defend it, with intelligence, but with great affection. The Church needs today more than ever to be loved by her children”.

Martín Descalzo, a priest between the press and literature

John Cantavella

Saint Paul

Martín Descalzo or journalism about the Church that no longer exists