I spent my childhood in Marseilles in the 1950s with parents marked by their commitment to the Resistance and the aftermath of the war. My mother served in the German campaign as a nurse after the Liberation of Paris. She was with Patton’s American troops at the opening of Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps. A moving experience for a very young woman and a difficult return to normal life.

My father subsequently suffered from serious mental disorders, which led my mother and me to live with my paternal grandparents. Simple people – my grandfather worked at Renault – who gave me a fundamental and rather fulfilling Christian education. I sang in a choir, discovering thanks to popular Catholic education movements two fields of culture that will irrigate my whole life: music and cinema.

Absence of the father

There are three key words in Catholicism: incarnation, passion and resurrection. Each of us goes through these three times of existence, in their spiritual perspective. The time of my incarnation has been long.

It begins with the war in Algeria, experienced all the more intensely since Marseille is a city facing North Africa and my mother had fought very actively to free herself from an occupier. Her experience had made her pessimistic about the human species, but she was convinced that it was necessary to fight for an essential value in her eyes: freedom.

In 1962, I am my mother in Paris. At the Lycée Buffon, Maurice Clavel and Michel Deguy teach philosophy. The political adventure of 1968 fulfills my expectations. Words and generosity run the streets. I exult. And at the same time, I carry a suffering linked to the absence of my father. I’m 20 and I don’t know what to do with my life. I undertake literary studies and discover the United States in 1970, staying in Chicago. I then left for London, where I frequented circles close to psychoanalysis.

Atypical forms of psychoses

As soon as I return to France, I undertake a personal analysis. Little by little, I realize that I have found exactly what I was looking for. I resumed studies in psychology and obtained the diploma of clinical psychologist necessary to work in the hospital. In Nanterre, I have a fabulous professional experience with a head of department open to psychoanalysis and the human value of madness. I am 30 years old and I finally find the place of my incarnation. Thanks to psychoanalysis, I found my breath.

At the Nanterre hospital, North African and sub-Saharan patients arrive with atypical forms of psychosis. They force us to ask ourselves about the influence of culture, and therefore of their religion, Islam, on psychic life. This is the period that corresponds to passion for me!

I resumed studies to become a lecturer, then a professor. At Paris 13 University in Villetaneuse (93), I created with an Algerian friend the DESS (equivalent to the current master 2, editor’s note) of intercultural clinical psychology, not without incomprehension of the State authorities, skeptical about the study of the great religious texts in a course of psychology. Anthropology and ethnology help us to make them understand that religion is not just a “private affair”.

The divine in the human

As a psychoanalyst, I deepen my interest in religious questions. An interest that was that of Freud. He has always defined himself as an atheist Jew assuming religious culture. But he was not opposed to the divine in the human, the alliance of the two forging what he called the “great man”. For Freud, psychoanalysis is an enterprise that aims to free oneself from useless beliefs. It’s about distancing oneself from the world of parents – our first gods! – and with the convictions that were those of the child, whatever they may be.

This is what psychoanalysis allows us to do insofar as it offers a space – a place apart, that we find nowhere else in society – to question the incomplete story that everyone tells about themselves. . This place, where only one person listens to you and tries to make you pay attention to what you have said, sends back an unprecedented echo. This echo causes changes that will allow you to change, to heal. Psychoanalysis allows access to greater freedom and the discovery of the three realities on which we are based: material, psychic and spiritual.

Of course, we are all in material reality with our bodies. But psychic reality is also part of our body. As for spiritual reality, it is at the crossroads of the other two. Freud, as a theoretician, was very interested in Judaism and Christianity. For him, monotheistic religions can bring the best, the taste of spirituality, and the worst, intellectual inhibition. But religion, in the 21ste century, can not be intellectual comfort. This is a question that I constantly find in the Scriptures, in the Bible and the Koran.

Fruitful interreligious dialogue

The Koran ? 45 years ago, the one who became my wife, Karima Berger, novelist, essayist, came into my life. Karima arrives in France to do her doctorate, she is Muslim, steeped in Algerian culture. Since then, we have not stopped talking about the difficulties inherent in this religious mix which is added to that of the sexes. With Karima, I encounter Islam, of which I knew nothing. The reading – stunning! – of the Koran led me to immerse myself in the Bible. The back and forth never stopped.

Between the Bible and the Koran, what a dialogue! It is extremely fruitful to move from one to the other, to read for example the episode in the life of Joseph in the Bible, to read the long sura Joseph in the Koran, the crucifixion of Jesus in the Gospels, the apparent crucifixion of Jesus in the Quran. It makes you think. And this is indeed what this word of the divine that unfolds in these two monuments asks of us. The Bible and the Koran, which have no author as such, are the repositories of a secular word that comes from elsewhere, whether we believe in it or not. The discovery of Islam allowed me to reconnect with my Christian origins.

This is where I have another shock: reading Paul allows me to meet a man gripped by the resurrection. For Paul, the key word of Christianity is resurrection. But not after death. The resurrection at the heart of life itself. That is to say, for everyone, to recognize themselves as definitively mortal, but also as absolutely alive. To experience yourself on both counts! We have this material and psychic life which we know will end – and it is necessary to know this – but we can also give ourselves the chance to access our spiritual reality by relying on our psychic life.

spiritual expectation

With Paul, I see that there is this part of myself which is oriented towards the divine, but which is part of the human in me, and which is the pledge that this life will find to be perpetuated. “beyond the curtain” as it says in the Epistle to the Hebrews. With Paul, the resurrection seems to me to be this vital experience which allows one to be alive while accepting one’s death. Down here, I’m already dead. But here below too, I have already been resuscitated. It is not a belief in immortality, but rather a living presence within myself. I imagine that death opens to this Life beyond life; it’s a bet.

All this leads to broadening the perspectives of a psychoanalysis and to recognizing the importance of religions. For me and for the people I have been able to support. It was of course a question of allowing my patients to free themselves from the symptoms which burdened them and prevented their blossoming, but not at all to deprive them of this spiritual expectation, to consider it only as an illusion. Nope ! Besides, we are beings who pass from one illusion to another – an illusion of higher quality, at best. To escape the mirages of nothingness, there is no reason to deprive oneself of illusions. You just have to ask them.

The stages of his life

1948 Born in Paris, then childhood in Marseille.

1969 Studied at the University Center of Vincennes.

1970 In Chicago, discovery of the African-American world.

1973 Start a psychoanalysis.

1977 Meets his future wife, Karima Berger.

1978 Clinical psychologist at the hospital in Nanterre.

1995 Created the DESS in clinical psychology at the University of Paris 13.

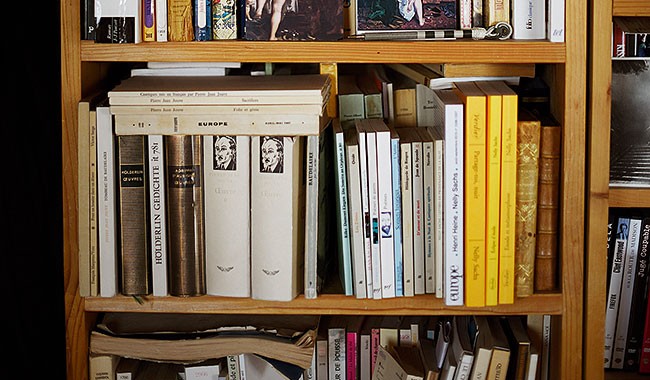

To read

The Mirror of the Prophet. Psychoanalyst and Islam, by Jean-Michel Hirt, Grasset, €19.90.

Paul, the apostle who “breathed crime”. Impulses and Resurrection, by Jean-Michel Hirt, Actes Sud, €12.

Renounce shipwreck. The drive at the service of the living, by Jean-Michel Hirt, Les Éditions d’Ithaque, €16.

The Likely Rise of John Coltrane, by Jean-Michel Hirt, Domens, €12.

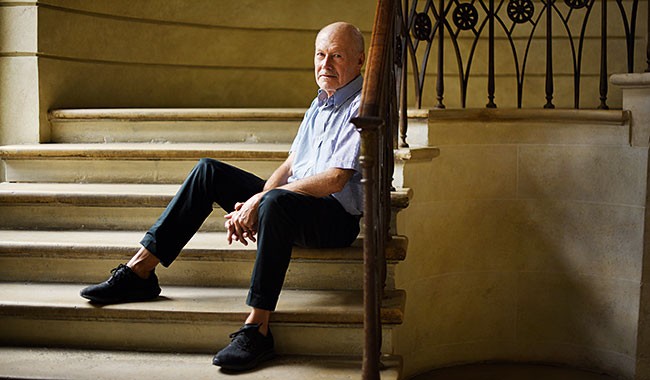

Jean-Michel Hirt: “In the 21st century, religion cannot be an intellectual comfort”