Christmas is the religious feast of the nativity, or of the incarnation of the son of God on earth.

Today, between dinner parties and Whatsapp greeting messages, few are interested in whether God became man in Christ. Let’s face it, he doesn’t give a damn to anyone.

But it wasn’t always like this.

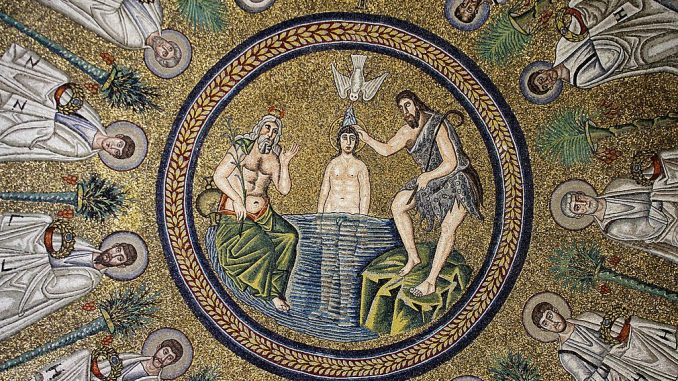

There was a time when Christology, that is, the essential part of Christian theology which studies and defines who and what Jesus Christ is, unleashed very heated religious and social conflicts, coming to threaten the very existence of Christianity.

The fourth century, the century of Arianism, was the most critical in the history of the Church which was on the verge of succumbing.

Arianism was the Christian heresy which, more than any other, had concrete possibilities of becoming the official doctrine of the Church: it was believed by bishops and local Churches, supported by emperors and entire peoples.

In 2007, Pope Benedict XVI affirmed that the situation of the Church after the Council of Nicaea in 325, which branded Arianism as heresy, was one of total chaos, and he recalled the words of Saint Basil who compared that era to a naval battle in the night, where no one knows the other anymore, where everyone is against everyone.

By denying the divinity of the figure of Jesus (although clearly declared in the Gospels), the Libyan presbyter and theologian Arius challenged Christianity at its roots by attacking the central dogma of his faith.

Arius did not disregard the Trinity and maintained that the Son of God is a being who participates in the nature of God the Father, but in an inferior and derivative way (subordinationism). For the theologian, God, unique, indivisible, eternal and therefore ungenerated principle, cannot share or transmit his divine essence to others and there was a time when the Word did not yet exist and when he was created by God at the beginning of time.

Consequently the Son, as “begotten” and not eternal, cannot participate in the substance of the Father (negation of consubstantiality), but at most can be a creature: certainly a superior creature, but finite (i.e. having a principle) and for this is different from the Father, who is instead infinite.

To speak of the unity of divine substance in the Father and the Son was for Arius an absurd affirmation of the gods or two.

Jesus was therefore “simply” an intermediary between God and the world, a Master rather than a Redeemer.

The Aryan Jesus was similar to the prophet Jesus mentioned in the Koran, the first of the prophets, after Mohammed.

If Ario had prevailed we would not have had the incarnation and therefore not even Christmas.

We would not even have had the unpacking of gifts and the photographic exhibitionism on social media of the happy family who, once a year, find themselves eating panettone under the decorated tree.

Who knows if the hypocrisy of this Secular Christmas and, as Pope Francis says, led astray by consumerism, manages to make the 32% of women (ISTAT) who have suffered physical or sexual violence pretend and post family warmth, especially within the home. Now that would be a miracle of Christmas, indeed incarnation!

Arius’s victory would have done incalculable damage to Christianity.

In hindsight, however, he would have spared us this now caricatured celebration in which everything is involved, except God.

Andrea Marsiletti

If the Arian heresy had won, there would have been no Christmas (by Andrea Marsiletti) –