It was while going up the Nile in 1707 that a shipwreck threw them to the bottom of the water. The manuscript of the four homilies was saved and transported to Rome. In 1984, for a period of four months, at the rate of 18 hours a day, Father Khalil Alwan went daily to the Vatican library where he consulted the surviving manuscript in the dark, using an ultraviolet light. The latter revealed the traces of the letters at the location of the ink erased by the water.

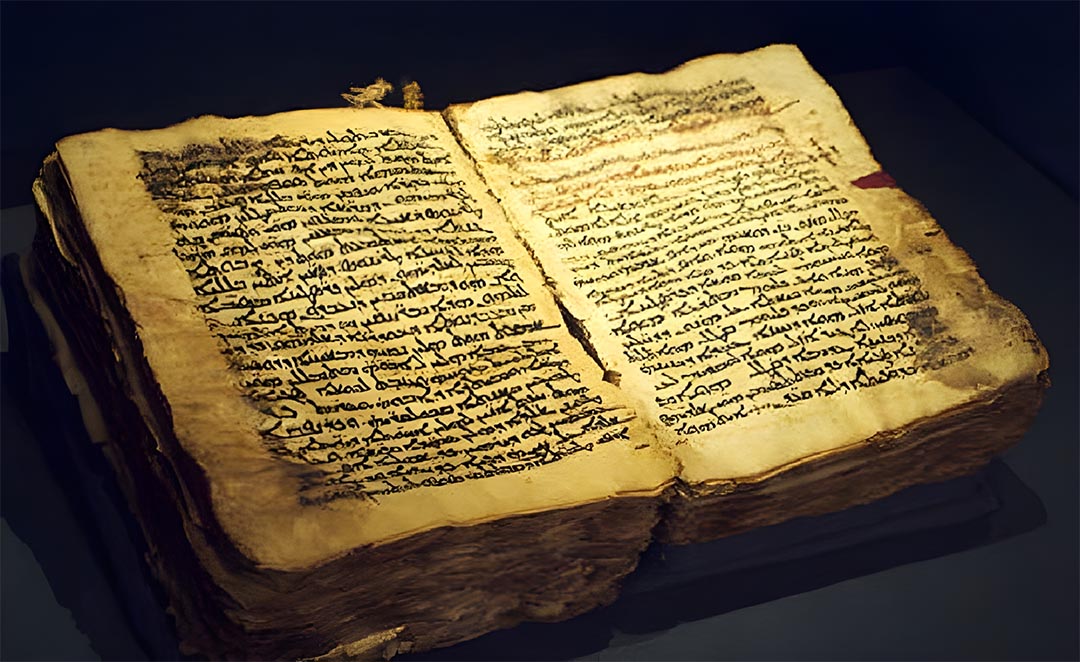

It is the story of a manuscript like no other, and of an eminent Maronite prelate, researcher, scholar and perseverant. It begins in the Middle Ages, around the 1200s, on the pages of a large reddish leather-bound manuscript. In a Syriac monastery in the desert of Scete (Ouadi Natroun) in Egypt, an anonymous scribe had copied there in his beautiful Syriac script the 2,200 verses of the four homilies of Saint Jacques de Saroug, composed at the beginning of the 6th century.

From Cyprus to the Vatican

It was on the island of Cyprus that in 1476, a certain George, a monk from Leukosia (now Nicosia), worked on its restoration. By 1499 the manuscript had become the property of Father Antoine Clepin, and in 1534 it passed to the priest Aaron. He ended up leaving Cyprus to find himself in Jerusalem in 1664, in the hands of the Syriac Metropolitan. We learn nevertheless, that at the beginning of the XVIIᵉ century, the work was again in Egypt since it is from there that it left to join the shelves of the Vatican library.

Since the founding of the Maronite College in Rome in 1584, the scholars of this institute traveled to the East to collect books for European libraries. The most renowned among these collectors were part of the Maronite Assemani dynasty. It was one of these missions that brought Elias Assemani to Egypt, enabling him to collect a large number of oriental works, including that of the four homilies of Saint Jacques de Saroug. It was while going up the Nile in 1707 that a shipwreck threw them to the bottom of the water. The manuscript of the four homilies was saved and transported to Rome where it was classified under the Vat code. Syr. 117.

Decryption

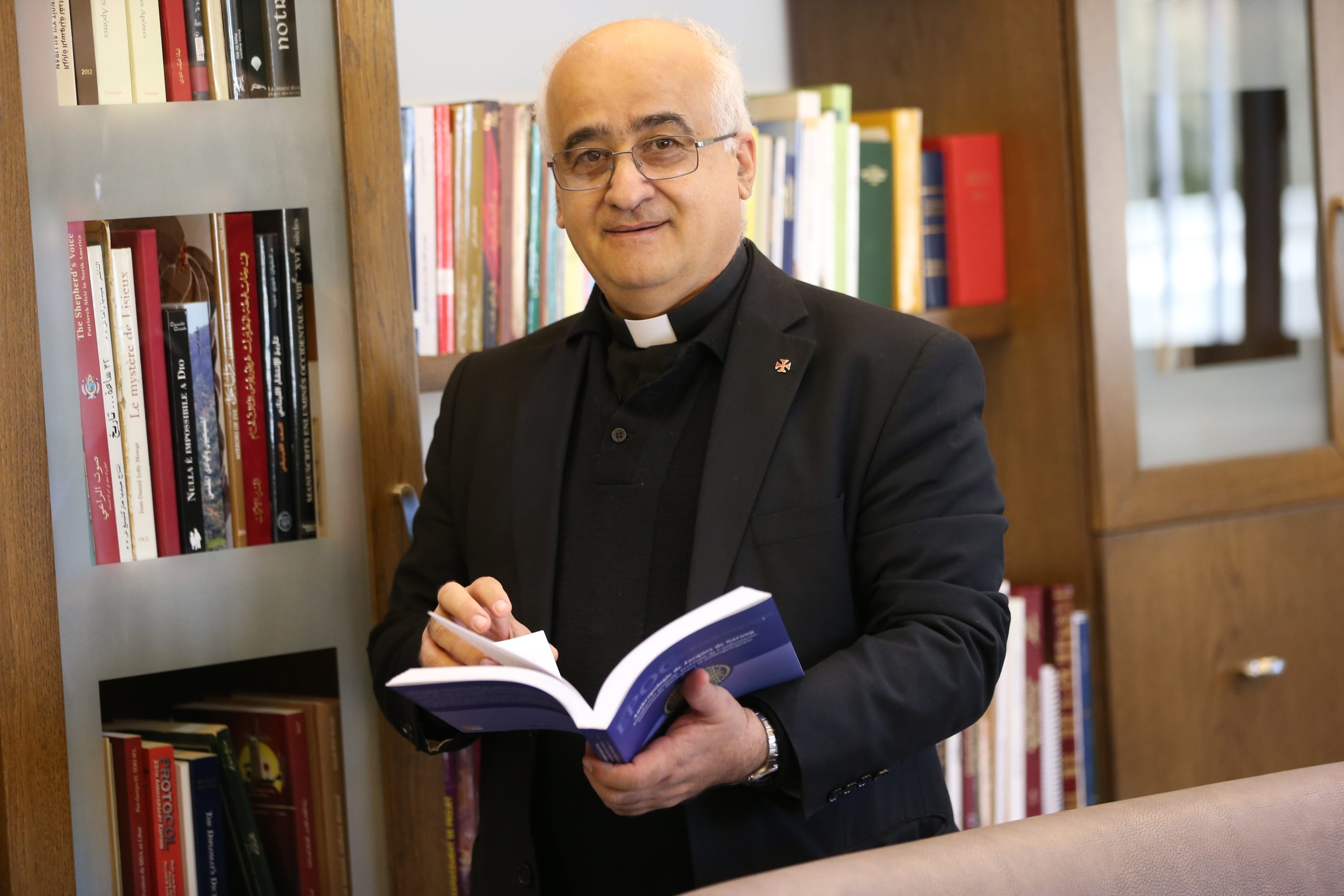

Like many Syriac volumes, it has been consulted or studied by scholars, including the great Joseph Simon Assemani. But part of the work could never be deciphered having been erased in the water during the sinking. It was not until the years 1984 to 1986 that another Maronite scholar, Father Kreimiste Khalil Alwan, set to work with all the necessary endurance and stubbornness. For a period of four months, at the rate of 18 hours a day, he went daily to the Vatican library where he consulted the surviving manuscript in the dark, using ultraviolet light. The latter revealed the traces of the letters at the location of the erased ink.

Like Saint Ephrem, Saint Jacques de Saroug composed mimré, or metrical homilies, in dodecasyllabic verse. It was by relying on these measurements that Father Alwan managed to insert the terms where the ink had not left the slightest trace. By respecting the number of syllables and the meaning of the sentence, he could suggest alternatives. He also had recourse to several Syriac anthologies, quotations in the writings of Grégoire Bar Hébraeus and Moshe Bar Képha, as well as Arabic translations of the same mimro allowing him to fill in the gaps. This process required three years of assiduous work since it was necessary to go to the various libraries, from Florence to London, in order to consult the corresponding manuscripts.

A rediscovery

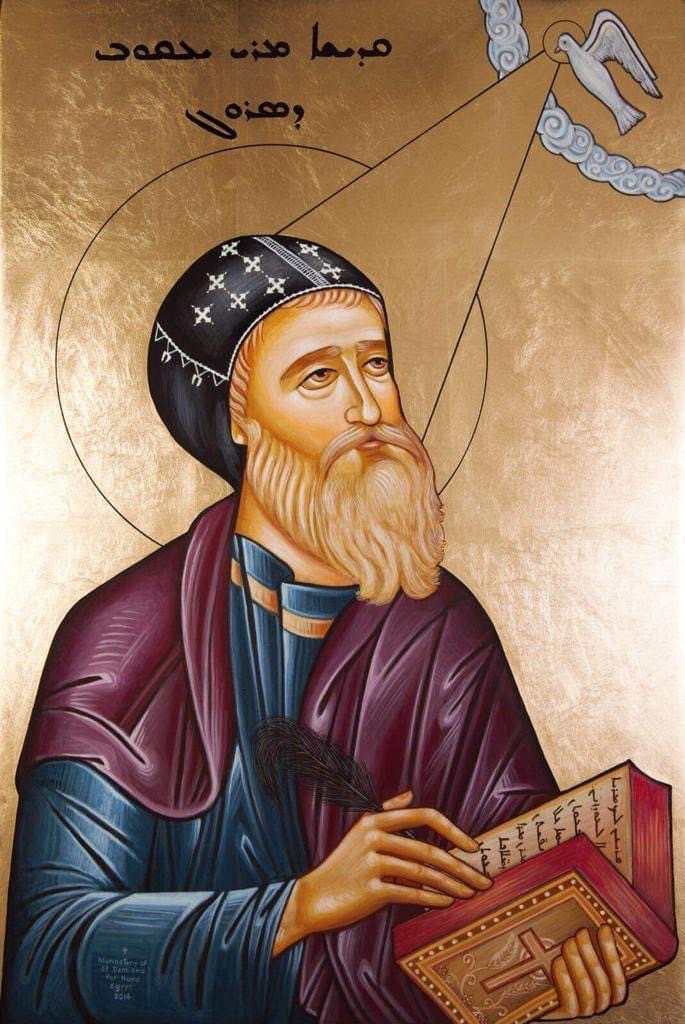

But Father Alwan succeeded, thanks to this colossal effort, in resurrecting the lost work of a great doctor of the Church. Died in 521, Saint Jacques, bishop of Saroug, is venerated by all Syriacs, whether they are Miaphysites such as the Jacobites (Syriac-Orthodox) or Chalcedonians such as the Maronites. Like Saint Ephrem “harp of the Holy Spirit”, he is nicknamed the “flute of the Holy Spirit” or even the “faithful zither of the Church”.

Father Alwan, who had been superior general of the congregation of Lebanese Maronite missionaries, known as Kreimists, and secretary general of the assembly of Catholic patriarchs and bishops of Lebanon, is now secretary general of the council of Catholic patriarchs of the East. He is currently one of the greatest specialists in the literature of Saint Jacques de Saroug.

A literary richness

This Syriac literature, which has ceased to be taught in our schools since 1943, would have so much to bring us in these times when humanity is looking for itself and trying to reconnect with nature. While Greek theology proceeds from a philosophical approach, that of the Syriacs is eminently anthropological. And the theme of Father Alwan’s doctorate was precisely the anthropology of Saint Jacques de Saroug.

Contrary to the Platonic school of Alexandria which despised matter, that of Antioch was Aristotelian and considered matter as a creation coming from God. This Antiochian mentality allowed a symbiosis between the spiritual and the material. For Saint Jacques de Saroug, the flesh will become immortal and “resurrect incorruptible”. The four elements (earth, air, water and fire) will spiritually become “one in indissoluble perfection”.

Anthropology and ecology

Syriac theology is an anthropological and ecological symphony. The school of Antioch praises it in the complementarity between man and nature. At death, the body returns to nature. “For the flesh rises, spiritual, in the new world, and it passes like the spirit through the thickness of natures”, we still read in the fourth homily of the Vat. Syr. 117.

Saint Jacques de Saroug disciple of Saint Ephrem, like him, transmitted Syriac spirituality in a poetic and colorful spirit. The disciple developed his master’s concepts and made them more accessible to the reader, Father Alwan tells us. Each idea is analyzed and supported according to a rigorous method which poses the thesis and the antithesis to then operate a long argument before establishing the synthesis. It proceeds above all from a phenomenon of actualization when it restores the Old Testament in the form of symbolisms announcing Christ. He transposes the various biblical scenes into ordinary moments of everyday life accessible to his contemporaries.

In love with Saint Jacques de Saroug, his spirituality, his poetry and his humanism, Father Alwan tells us how lucky we are as Maronites, to be able to learn it and pass it on in his authentic words. Unlike the Copts who inherited it in its Arabic translation, we have always read, written and sung it in our Syriac language.