After photography was accepted as an autonomous artistic medium, fundamentally after the avant-gardes of the last century, many authors, also in America, began to push the limits of perception to go beyond what is strictly visible.

One of the earliest proponents of that quest, both in image and word, was Minor White, who, after graduating with a degree in botany from the University of Minnesota, was named a Works Progress Administration “Creative Photographer.” In 1955 he began training in comparative religion and, since then, his work has been marked by a deep sense of spirituality, being the narrative sequence of images, which he called stills cinemahis preferred method when presenting his production.

This way of doing things can be seen in images such as Lake Road, Rochester: we see two tarpaulins arranged in folds in front of a concrete wall, with a ladder rising between them; the movement of the canvas is at once animated and elegiac, like the nervous and rapid flapping of wings of a caged bird. For its part, the vertical and narrow format of Mission District, San Francisco demonstrated his skill in choosing the essential element from his negative to convey the desired sentiment, and the radical cropping also leads us to believe that, from the artist’s point of view, the only element that should not be manipulated in the creation of a good photo is the author’s vision. Both works were part of the autobiographical series “Sequence 13: Return to the Bud” and were first exhibited at Eastman House in 1957, when Minor wrote: He always photographed found objects (…) the best have always been photographs that found themselves. In his view, there are two ways to be creative: The first is achieved by photographing the subject itself in a way that reveals its character; the second, choosing a subject to photograph that illustrates an idea that until then only existed in the photographer’s mind.

If we look at the picture the three thirds, we can read it literally, as a reference to the three different formal elements of a print: clouds reflected in a window, putty seeping through a boarded-up opening, and the jagged remains of broken window pane. The title makes us understand that the work must be understood as the sum of its parts and that, therefore, it represents a whole. Tripartite articulations were common in his production and contained both spiritual and formal meaning for him.

White was director of exhibitions at George Eastman House itself and editor of its magazine picture, as well as a photographer, editor and educator; Stieglitz, Edward Weston, and Ansel Adams were his mentors, and Chiarenza and Caponigro were his students. In 1952, together with Adams, Beaumony, Nancy Newhall, Dorothea Lange, and Barbara Morgan, he founded the magazine Openingof which he would be editor for more than two decades.

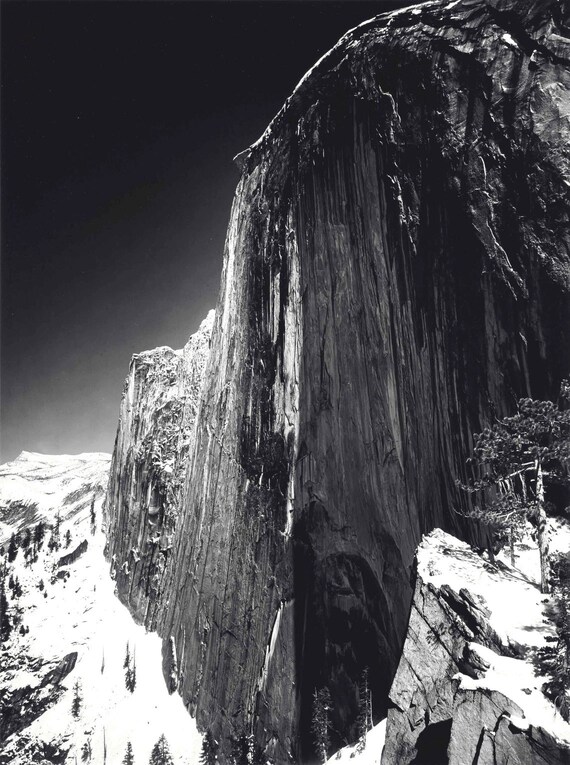

Adams was born in San Francisco and took his first photos, with a Kodak Brownie, during a visit to Yosemite Valley with his parents in 1916, an experience he described as supreme, so intense that it was almost painful (sublime, finally). He returned there every summer, he became a mountaineer and, above all, an environmentalist; his works would help increase visits to national parks. One of his most famous was taken in 1927: it is about Monolith, the face of Half Dome.

After meeting Paul Strand in 1930 and considering his negatives a revelation, he decided to devote himself to photography. Surprisingly or not, his first works were pictorialist and romantic in style, but in 1931 he had a kind of revelation (he told it that way), he became aware that this discipline could constitute a pure art form and he abandoned that path to become one of the founding members of the f/64 Group, who extolled the expressive potential of direct photography.

In Lake Cliffs, Kaweah Gap he demonstrated the potential of this medium through tonalities and details and in 1940 he became one of the founders of the photography department of the MoMA in New York (this was, in turn, the first museum to have it).

One of his most emblematic images would arrive the following year: it is about Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, where we can see that behind his art lies the calculation of a technician. He printed two versions of this work: one in which the sky appears blackish gray, twilight, and another more famous one in which he printed the sky with a much darker hue, creating strong contrasts and highlighting each cemetery cross that appears in the margin. lower.

Wave Sequence III, California Coast, meanwhile, reveals Adams’s musical background; he said that the negative is the score and the copy, the performance. In the layers of this work, which range from almost pure white to black passing through every shade of gray, the sea resonates with all its sonorous scale. He wrote: Who can define the moods of wild places, the meanings of nature in realms beyond material use? Here, the worlds of experience lie beyond history and science. The qualities and moods of nature and the revelations of art are equally difficult to define; we can only apprehend them in the depths of our perceptive spirit.

In this brief review of American photographers who took our gaze a little further, we will also refer to Harry Callahan. An engineer, he first became interested in the image as a hobby and later, during a couple of weekend sessions at the Detroit Photo Guild, he looked at the work of Ansel Adams, who discovered the potential of the medium.

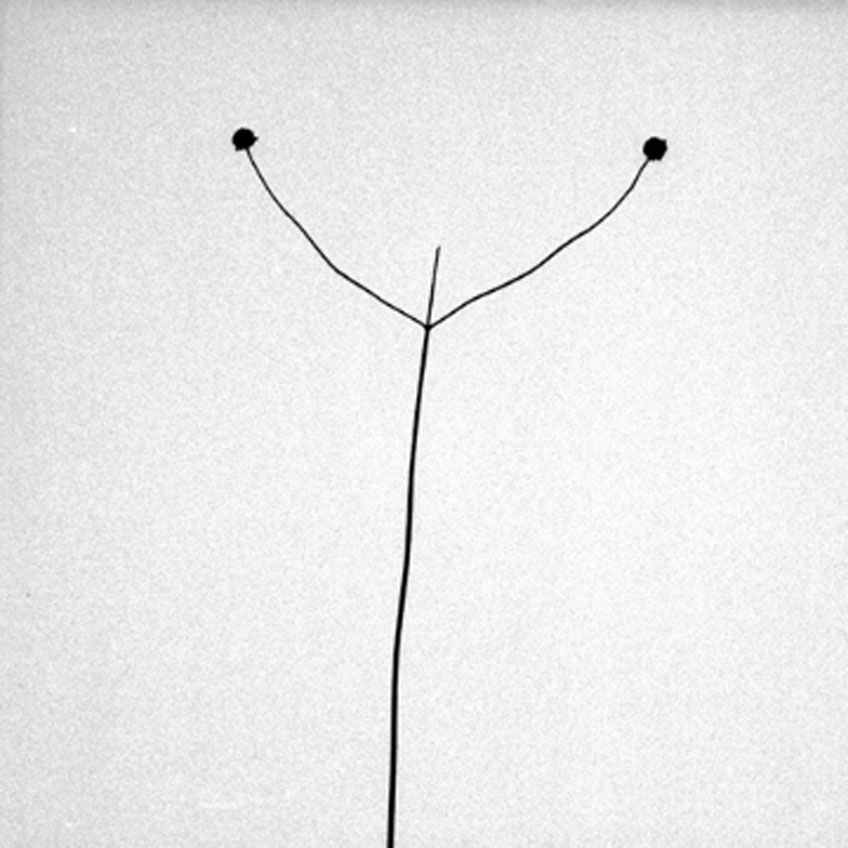

In 1945 he spent six months in New York, immersing himself in his new chosen profession, and the following year, none other than Moholy-Nagy appointed him an instructor at the Institute of Design in Chicago. The portraits he took of his wife Eleanor are among the most lyrical and moving in the history of this medium, and the image of her of a thin branch on snow, titled simply detroitis a triumph of abstract minimalism.

His explanations were as elegant and succinct as his photos: It is the subject that counts. I am interested in showing the subject in a new way, in order to intensify it. A photo is capable of capturing a moment (and this is the crux of the matter) that people can’t always see.

Harry Callahan: A photo is capable of capturing a moment that people cannot always see.

In 1935, Italian landscape architect Frederick Sommer settled in Arizona for health reasons, and his encounters with Weston and Stieglitz would encourage him to take photography more seriously. His initial imagery offers surreal touches: although he was never associated with any collective, he worked with Man Ray and Max Ernst. The anatomy of poultry would be a recurring theme in his work: the image eight young roosters it is an anatomical grid of eviscerated parts that seeks, not so much to impress the viewer, as to express a strange beauty and culmination of the moon shows a torn and worn photo of a dancing couple that nature and time have melted into the rock.

Aaron Siskind, finally, tried to introduce types of expression from his literary and musical forays into his production. His images of rocks on Martha’s Vineyard and graffiti on a Chicago wall seem worlds apart from his previous documentary work, even though they share his taste for balance. In a prolific career that took him from documentary to abstract photography, he maintained his influence on the American scene, first in the Photo League and later, invited by Harry Callahan, as an instructor at the Institute of Design in Chicago.

Minor White, Ansel Adams, Callahan and what we don’t see in the photos