On Saturday, November 19, after the funeral rites, after having said goodbye to my dear friend at the cinerary portal, where the last propitiatory fire awaited him, I returned to his house in Olmué, where we toasted the gods of the word, auguring a luminous reception in the nameless place.

By Edmund Moure Rojas

Posted on 24.11.2022

SExactly six days before his 90th birthday, Hernán Ortega Parada (1932 – 2022) said goodbye to this world and entered the unknown labyrinths of eternity; we presume that the Parnassus of the elect.

Emulating César Vallejo, it was a Thursday, at his house in Granizo, Olmué, on the slopes of La Campana hill. It had been three years since the burning of his three-story house, built for thirty years, stone on stone and then wood until the verticality of the blue sky of the region.

Thorough writer, like someone who lives for the joy of the word, in that forced duplicity that daily subsistence imposes on us; narrator of black stories, essayist, also a poet; tireless researcher, founder of one of the best literature magazines in Chile, the fine and careful smellin whose pages we had the honor of publishing our incipient critical commentary and short narrative texts.

Generous and affable, within a trade where vanity, egocentrism and backsliding tend to reign. On the fourth floor of Casa Dino, located on Avenida España corner Blanco Encalada, in front of Club Hípico de Santiago, Hernán received us, in the evening, in the city full of threatening shadows, during that “long night of stone” in the one that passed the atrocious and barbaric military and business dictatorship commanded by Augusto Pinochet.

Jorge Calvo, Ramón Camaño, Paz Molina, Martín Cerda, Alfonso Calderón, his daughters Lila and Teresa, Natasha Valdés, the chronicler and others I cannot remember, we engaged in passionate conversations, dialogues and even disputes about the passion that we united by the creative word.

Let us recall here a fundamental part of his solid literary work:

—Historical panorama of Aysén (1959).

—ecce homo (poetry, 1964).

—Stories about Aysén (1966).

—The death of the nightingale (poetry, 1992).

—Enrique Gómez Correa, architecture of the writer (essay, 1999).

—Jorge Teillier, architecture of the writer (essay, 2004).

—Aysén, historical and cultural panorama of the XI Region (2004).

—Thinking, education, reading and literary creation (essay, 2007).

—Ludwig Zeller, architecture of the writer (essay, 2009).

—Minimal essays, psychology and literature (2012).

—Poems of evil, porte des poetes (France, 2012).

—Raúl Zurita, architecture of the writer (essay, 2014).

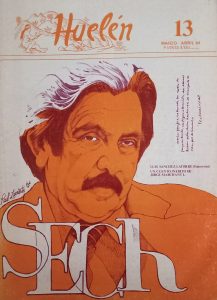

“Smell” No. 13 (1984)

Literature as a permanence

Short, direct, sometimes surly and reticent of affectionate gestures —as his son Pablo defined him—, remembering the difficult interpersonal relationships in his childhood and adolescence, with that father absorbed in books, stealing the time of family life to devote it to the books.

That’s how love was rough for him; This is how heartbreak and abandonment hit him, after the tragedy of the fire that devastated books, files, pages of methodical studies, documents and testimonies from 70 years of Chilean and universal literature. In that moment of harsh solitude, Pablo accompanied him and was able to partially rebuild that house, rebuilding it from the ashes.

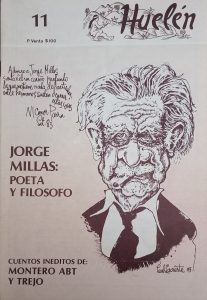

From the magazine collection smell, I choose numbers 10, 11 and 13, dedicated, respectively, to Raúl Zurita, Jorge Millas and Luis Sánchez Latorre (Filebo). The covers offer us the young face of the poet, the reflective face of the philosopher and the mocking face of the great journalist and writer.

The portraits are the work of cartoonist Paul Lacreste, a friend of Hernán Ortega, until he discovered that the graphic artist was associated with security agents of the dictatorship, a fact that would cause a violent rupture.

In those 80s, artists and intellectuals were considered dangerous enemies of the regime; they had to be watched and, in “extreme cases,” silenced. Hernán never compromised with the covert felony or with the hypocrisy of the “happy idiots.”

In the editorial of smell N° 10, Hernán Ortega writes an essential text for his commendable purpose, made a permanent action thanks to the attribute of his will. He tells us:

We would like to do a little history of the future. But, inexorably, we look back. We can touch the present. A great silence weighs on the city and due to gadgets and mysteries of life, on Tuesday the 12th, almost at dawn, we close the edition.

December 1980 and smell It is already a body with a face and a word of invocation: ‘Gabriela’s unforgettable face, mother of a new and profound Chileanness of which there is still no awareness in the long country.’

We thought, in passing, how much Chileanness was suggested by the Mistral, a Benjamín Subercaseaux, a Joaquín Edwards Bello. Through an alert group; even through a strong and free dissidence of thought. How strong and proud is a people that can think. THINKING is the WORD.

Literature takes the Word from Reality and makes it Art, Permanence. From real life he makes her phosphorescent. And, again, Rimbaud: ‘All new art requires new forms’. Rimbaud, an outsider, a cyst in society, makes a change in the world through his art and its freedom.

The magma of these materials forms the underlying concerns of this small company called smell. We are interested in the literary environment to which we appear. We are particularly interested in the LITERARY PROFESSION. That how to know, assimilate, automate —in that progression— the technical bases of this career. And that it is not a second, third or fourth personal activity. And if it is, it doesn’t matter. Thinking and writing will bring pleasure and pain, the summary of existence.

“Smell” No. 11 (1983)

The signs of a writing

Lucid and accurate, Hernán Ortega gives us here the summary of his vital poetics, the synthesis of a long and fruitful existence for the sake of a passion that time does not weaken, not even with the anguish of decrepitude, not even with the cunning ash who wants to impose oblivion.

In his last days, stretched out in his hospital bed, Pablo, his grandson, would read him stories by famous authors, including that Horacio Quiroga, the tormented Uruguayan he loved to reread so much. The youthful words took him to rest and Pablo stopped reading when he heard the slow rhythm of the old man’s tired breathing.

Thus he gave himself up to eternal sleep, in his house in Olmué, rebuilt, although there was no longer any vigor for the restoration itself. Hernán loved that wooded corner next to La Campana. This is how he expresses it, in part of the prologue to his remarkable essay Jorge Teillier, architecture of the writer:

Consciously or unconsciously, in the course of this work on Jorge Teillier, Enrique Gómez Correa will appear to me, just as he was prefigured in a previous book. I do not yet expect to establish those pretentious theoretical relationships that could -perhaps after a third study- emerge as a tree or, more modestly, as a balanced bush.

My relationship with nature is secret and intense, but although the lives and works of two poets —simply and eternally poets— interest and excite me, it is no less true that that ivy called “sigh” speaks to me of ‘wonders’ that my mother cultivated with ingenuous wisdom in El Llano and that I have transplanted with mysterious impulse in my refuge in Olmué, where today it rises above the branches of shrubs and boldos and makes lights shine like blue galaxies far above, surrounding the treetops. the tall molles and the majestic quillay.

Both that simple nature, sometimes intervened, and these great cultivators of spirituality —Enrique and Jorge— move me because they correspond, together, to an ineffable and exuberant manifestation of life. Under those signs, I write.

On Saturday, November 19, after the funeral rites, after having said goodbye to my dear friend at the cinerary portal, where the last propitiatory fire awaited him, I returned to his house in Olmué, where we toasted the gods of the word, auguring a luminous reception in the nameless place.

“Come here whenever you want,” Pablo said to me as we said goodbye under the bright maitenes of the villa.

“I’ll come,” I replied, although I can no longer find myself with his tall figure and his leisurely movements, like a kind of wise Lincoln advocating freedom at all costs in literature.

***

Edmund Moure Rojaswriter, poet and chronicler, became president of the Chilean Writers Society (Sech) in 1989, after the democratic mandate of Poli Délano, and was also the manager and founder of the Center for Galician Studies at the Institute of Advanced Studies from the University of Santiago de Chile, a house of higher studies where he held the chair of Galician Language and Culture for eleven years.

He has published twenty-four books, eighteen in South America and six of them in Europe. In 1997 she won a first prize in Spain for her essay Chiloé and Galicia, magical borders. Its last title put into circulation is the volume of chronicles passing memories.

He currently works as director and head of the newspaper Cinema and Literature.

Edmund Moure Rojas

Outstanding image: Hernán Ortega Parada and Edmundo Moure Rojas.