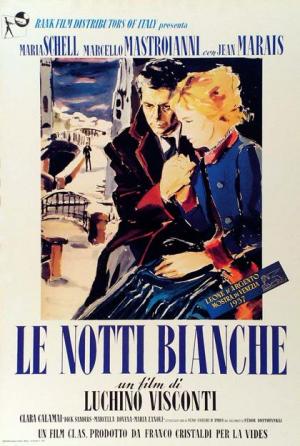

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s perspective in the writing of his short novel of 1848 was confused in terms of love and solitude, at least in terms of a progressive search for the moral improvement of his literature in general, but Luchino Visconti —in this audiovisual translation from 1957—takes that essential ambiguity to the more political and ideological plane of the phantasmagorical, in the context of post-war Italy.

By Horace Ramirez

Posted on 15.8.2022

ANDn the latitudes of St. Petersburg, at a certain time of the year, the sun after sinking below the horizon is close enough to it that the night is never deep and dark at all. Some of the sunset lasts all night and in those lands, these nights are called “white nights”.

The indecision of the sky, its ambiguity, accompanies the duality of White Nights (Le notti bianchi), the collected film by Luchino Visconti from 1957 and based on a story by Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Thus, the main concession that Visconti makes for the making of his film in relation to the original story, is to move the alleys of San Petersburgo to Tuscany, in the andurriales of Livorno, and more specifically to the stages of the Cinecittà.

It all looks slightly contrived, but while more realistic effects had been achieved in other films made at the same legendary film and television complex, Visconti—with a touch reminiscent of Fellini’s unmasked artifice—asks Giuseppe Rottuno, his director of photography, that everything: “it has to look like it’s fake, but when you start to think it’s fake, it has to look like it’s real.”

The ambiguity must have been present up to this level because Visconti applied the dualistic principles that Dostoevsky also experienced in his physical decline shortly before being deported to Siberia. his novel The double he had been little more than a failure and his orthodox Christian faith collided with the atheism of his great friend, the critic Vissario Bielinsky.

The dreams of Mario, an always sublime and handsome Marcello Mastroiani, fit into the ideal socialist model that the Russian was approaching before being arrested and deported. Dostoevsky’s perspective was ambiguous regarding love and loneliness in the progressive search for moral improvement, but Visconti takes that ambiguity to the more political and ideological plane of the real and the illusory.

The political appears in the dilemma of Natalia (the sweet and beautiful Maria Schell) who, as if flying between illusions and fairy tales, is dragged towards social decadence by the hand of the mysterious tenant (Jean Marais). The real world, for its part, is that of the neon signs, that of the white stray dog, that of the Esso service station that practically opens and closes the film.

And so, while Dostoevsky longed for a revolution that would put an end to the absolutist domination of tsarism, Visconti dreamed of a center-left government, or directly left, that would destroy the Christian Democracy in power.

But also White Nights analyzes a social dimension: Natalia takes refuge in her dream world and fantasy, waiting for a prince to rescue her and refusing the real man who offers her the redemption of a carnal and true love.

This ambiguity reaches a darker extreme than in the Russian’s story, making the moment of happy reality collide head-on with the endless disenchantment of lost love.

A more intimate layer of love and spirituality

The fundamental solitude of the character of Mario appears in the opening scenes: open and uninhabited spaces, or populated by shadows and silhouettes that do not seem to be able to interact with him in any way. The city is a labyrinth that finishes outlining it.

Natalia on the bridge is the engine of ambiguity: that bridge, that channel of calm waters is the border between the dreamed and the real. Natalia is a languid and fragile being, with one of the sweetest and almost eternally childlike faces that the heaven of cinema has ever given, but she is a woman —she belongs to the real world, although she cannot live it— and for that reason she is capable of awakening the true love that Mario, a vulgar and comically materialistic office worker, discovers in himself, and that makes him discover himself in a more intimate layer of love and spirituality.

The stories of Natalia’s life appear especially in a scene between the old women and through a cyclorama —which avoids the cut of a flashback— takes the story to another instance related to the tenant.

Meanwhile, Mario continues to investigate to discover what for him has more of romantic madness than truth. However, Natalia’s nights continue to be lost in permanent solitary sleep for that tenant. He falls in love with Natalia but shortly after living in the house he had to leave, leaving only a weak promise of return.

The character of the tenant is almost an oneiric vision that Visconti extracts from films that Jean Marais made with Jean Cocteau, such as The two-headed eagle of 1948, and that surreal air allows Visconti to develop another atmosphere for Natalia that flies over romantic madness, which, instead of frightening Mario even more in love with her, falling into a delicate and at the same time vertiginous folie à deux.

The bridge where Mario discovers Natalia and where she sobs is, as we said, a border of a world that in turn is fragmented between memories and presents; a virtual scenario where she cries in front of everyone because of an intimate problem, and where her mind is inhabited by a very old grandmother —who holds her back with a pin in her skirt— and ghosts and absences that confront beings real. Mario, from her realistic tradition, co-participates trying to extract her towards the reality of a “normal” world.

The temporary and the permanent; Yesterday and today; the popular and the cultured coexist in the script, and the latter appears in the opposition between going to the opera with the old women and the tenant (always on the verge of a kiss) and the lewd dance to the music of Bill Halley and his kites (doubling the length of the theme Thirteen Women for the investigation to be deeper).

And at this point, Natalia begins to relax and Mario —after a dance that mimics the best of Jerry Lewis, and which highlights his acting quality even more—, does a carefree pantomime that leads Natalia to finally laugh and dance.

“White Nights” (1957)

The psychological ambiguities of the characters

But it’s ten o’clock at night, and Natalia finally realizes that the time has come for the tenant to return, as promised. The spiritual cut that Dostoevsky raises is in Visconti more of a social type: the one who has a job —like Mario—, and the homeless who live on the street, between one world and another, cohabit the love for Mario that seems to emerge definitively in Natalia and the moments of true happiness that he experiences for the first time.

Everything happens when they decide to travel along the border between both worlds, crossing and overcoming —apparently— the division between the real and the illusory, using a boat that will navigate the canal. The whiteness of the night in the film occurs not only in the ashy light of the sky but also in the snowfall —brief— that accompanies them in the boat.

Both live in that moment the epiphany of reality, light and love, but the silhouette of the tenant waiting on the other street cuts everything off. The mists, the foghorns of the boats, the diffuse lights and silhouettes and the formidable music of Nino Rota, visually imbibe the psychological ambiguities of the characters, which is the great plastic triumph of this film.

Finally, the physical size of the tenant, his black clothes; His hieratic speechlessness rips the woman he had begun to love out of Mario’s hands.

In Dostoevsky’s story we read: “Nastenka (Anastasia), who will this man be? I asked in a low voice. —It’s him!, she murmured, and took my arm trembling…”, after that moment the literary and cinematographic endings are unleashed… brief in the case of the writer, but longer, with more to say, at the end of Visconti: that dark and enigmatic man all dressed in black awaits her with an expressionless face, his back to the farewell between Natalia and Mario.

The camera faces him so that we can see how he literally wraps her in his coat and, almost as a metaphor for death (I remember playing that at a distant Cineclub meeting in Buenos Aires), takes her from Mario, rips her from us and also eradicates it from the world.

Mario, resigned, returns to his reality.

He returns to the lonely streets, to the white dog that recognizes him and to the Esso service station.

***

Trailer:

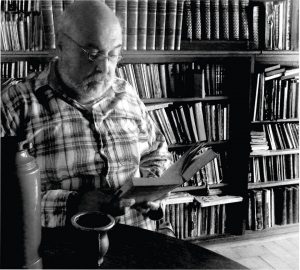

Horacio Carlos Ramirez

Horacio Carlos Ramirez (1956) was born in the city of Bernal, Partido de Quilmes, in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentine Republic. After finishing his secondary studies he began to study ecology at the Faculty and Museum of Natural Sciences of La Plata, but after a few years:

I recognized that I studied life not for its sake, but for the aesthetics of life. It was a time of hard decisions, until I met a series of authors and an anthropologist from the Faculty —Dr. Héctor Blas Lahitte— who guided me towards a field where instrumental science went hand in hand with aesthetic thought in their more abstract and at the same time charming facets… but that intertwining had a price, which was to redirect everything again… and so I began to study aesthetics, anthropology and symbology, cinema, poetry on my own. Everything led everywhere, everything opened up to a network of knowledge that was transformed into self-promoting and self-justifying knowledge.

Religion —the so-called ‘Mormonism’— ended up giving a spiritual closure to the matter that fit with a perfection that already seemed to me of no return… The practice of painting —I made several collective and individual exhibitions— ended up throwing me on the beaches of the poetry. Today I write poetry and theorize about poetry, both Western and in the realm of Japanese haiku. I give talks on human symbolism and various aspects of aesthetics in general and the aesthetics of life, where I try to show how a fly and a stone angel have more elements in common than mutual segregations, and to help unravel the entanglement without sense to which our civilization is subjected with a deficient vision of science that makes us enter into a permanent environmental and social conflict… The human seems to be a species that, from pure richness and at the same time disoriented, is in permanent conflict with everything. that surrounds her and with herself…

I have written four books of poetry, the last one with some stories and a series of reflections, and I am finishing two texts that may one day see the light: one on universal symbology and another on poetic theory.

Horacio Ramírez currently lives with his family in the town of Reta, also in the province of Buenos Aires, in the district of Tres Arroyos, on the Atlantic coast (about 600 kilometers from his birthplace), giving guided talks on ecology, epistemology and night walks to appreciate the sky and its system of astrological symbols and the stories that gave rise to it in the different ancient traditions.

*This article was written to be published exclusively by the Journal Cinema and Literature.

Outstanding image: Le notti bianche (1957).

[5 años de CyL] “White Nights”: The profound reality of the illusory – Cinema and Literature