“Maybe I am obsessive. That sin gets bigger when I talk about India.” With this declaration of parts starts crowned with flies (2012), account of Margo Glantz’s trips to that country. I sense that he is fascinated by the puny contrasts of her streets: stench, mutilated people, garbage, cows, shit, along with a withering aesthetic, spirituality, saris of impossible beauty. The writer is dazzled by those “palaces and misery” as cultural axes that coincide. She, with a clean face, assumes the paradox: “I have to visit that country again, I love it and I hate it”.

CONNECT OPPOSITES

Glantz is stimulated by the density of meanings because he enjoys showing relationships, linking the unconnected. In his work, expressions such as “I associate”, “it looks like” and “it reminds me” link separated realities. In for a brief injury (2016) recounts that he visits the dentist a thousand times and there he thinks that a woman in a burqa cannot fix her teeth, that the dental bridge is like a designer shoe, that Ferragamo made lasts tailored to each client.

The emeritus professor at UNAM is not only obsessed with India. That novel “about teeth” took him more than fifteen years; in it she humorously acknowledges being “repetitive, nagging”. Indeed, her books often return to subjects that are distant from each other (or not) such as literature, museums, the vision of gender, the lives of musicians, the poet Rimbaud, fashion.

It is insistent, very insistent, with the painter Francis Bacon and the mouths he portrays. I think he’s attracted to the Irishman’s display of hobbies. She says of him in Fury: “He liked to exercise looking at the most diverse images; In his studio, a montage brought together, pinned to the wall with thumbtacks, portraits of Goebbels, Innocent X painted by Velázquez, a photo of Baudelaire, a slaughterhouse exhibiting huge chunks of meat held up by hooks, a magnified photograph of an open mouth with the teeth very battered and polished by light, Muybridge’s photographs of characters in movement”.

All things considered, Bacon’s tastes are very Margo: they exhibit an insatiable, fragmentary, chaotic itch for knowledge. That voracity allows the essayist to relate unrelated events, which he revisits from time to time. That is why a book of his continues the thread of the previous ones: the protagonists reappear and new ones are added.

I put another case: in several moments of Fury reels off observations about the painter Stanley Spencer. He points out how the artist captured himself with his wife, “both exaggerated and grotesque with a nudity that brought them dangerously close to a slaughterhouse animality, a vision of the human body that Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud would never have been able to paint without Spencer, a vision that annihilated totally an English form of sexuality and way of life, which we know as Victorian”. There is the hinge that articulates: both in Fury (2007) as in for a brief injury (2016) interweaves biographical features and digressions on Spencer (born in the 19th century) and Bacon (in the 20th). The set proposes a multidisciplinary analysis.

Like someone who doesn’t want the thing, the author formulates small theses, combining readings and literary theory with sociology, art history and history of private life, to say the least. Which is saying a lot.

A BUILDING OF INTERESTS

Thanks to resources like this one, his narrative simulates a spiral, that “flat curve that revolves around a point, moving away from it in each one of them” (RAE). In effect, Margo distances herself from the central themes and returns to them, although he has already enriched them with affinities. Of oppositions. This kind of lucid game demands not only memory and a very robust cultural background; also the sagacity to find similarities vs. disagreements and crossing lines, to architect a building of interests with unpredictable assemblages.

Another example: when commenting on photos of the magazine Vanity Fair it highlights that Mobutu, dictator of the Congo, appears dressed “à la Versace”, while on the next page starving models advertise Calvin Klein. Then he connects both events: “Is there some secret perversion in the fact that in that article dedicated to Africa there does not appear (modesty, perhaps?) any representation of the thousands of skeletal children that Mobutu’s dictatorship and the war produced? It would seem that it is an exact symmetry: the anorexia of abundance and the anorexia of poverty: they coexist in harmony”. Thus, the author reveals to the reader a fertile link: the one that brings the dictator closer to a model and, by extension, abounds on the identity that is embedded in the dress, the sociology of what we wear. She reminds me of obsessive ramblings about saris in India. Everything intertwines and lights up.

CHALLENGING OPERATION

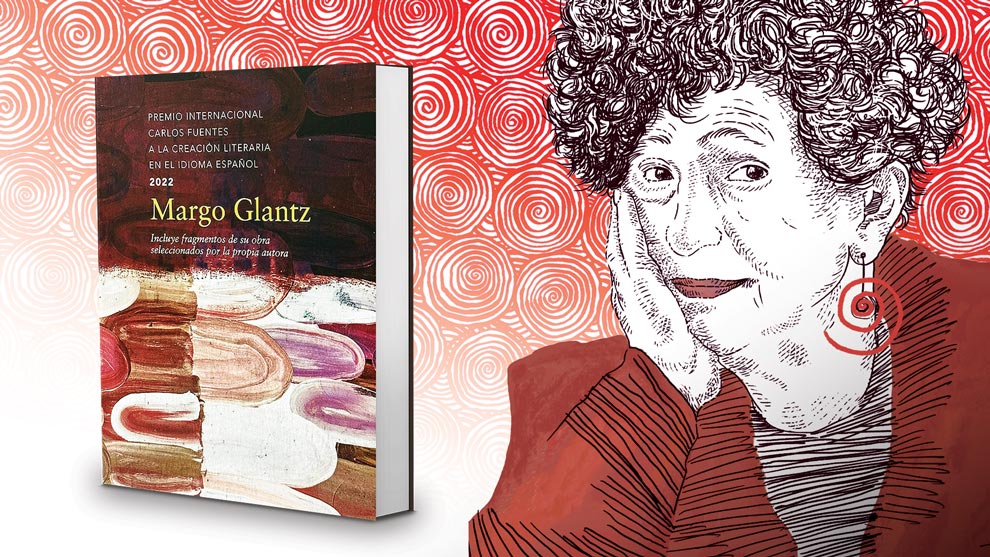

Margo Glantz is very deserving of the Carlos Fuentes 2022 International Prize, awarded by the Ministry of Culture and UNAM. creator of Point, for decades has been a tenacious promoter of reading and writing, both in our university and outside it. Furthermore, reading it is a pleasant exercise that teaches us to look without naivete, broadens the framework of understanding, recovers the oblique approach. In other words: her complete work enriches the points from which to scrutinize. I can’t think of more challenging and generous operations for the writer, for the university academic.

Now what Paul Celan wrote comes to mind and she quotes: “If we could think with your teeth…”. It’s.