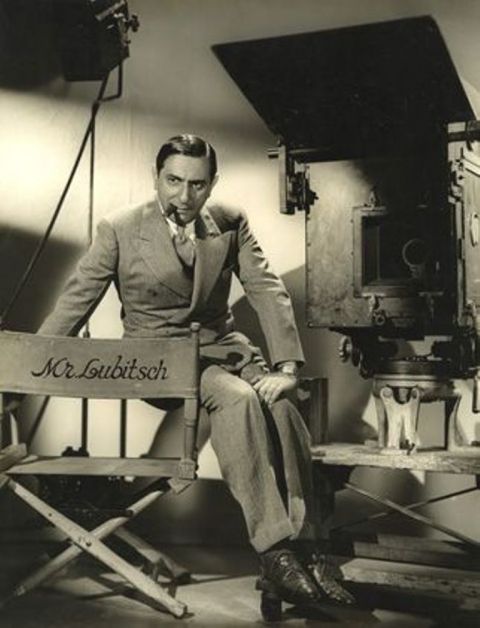

130 years after his birth, a portrait of Ernst Lubitsch (Berlin, 1892 – Los Angeles, 1947), a master of sophisticated comedy who trained in Germany but built his career in Hollywood, without however succumbing to the lure of the “star system”. A great gentleman on the set as in life, he has signed timeless films that would be worth rediscovering.

From an Ashkenazi Jewish family, Lubitsch possessed a particular talent for observing and narrating that very human characteristic of looking at life from the side with the nonchalance of someone who seems to know a lot, and instead it turns out that he is only bluffing; in his films one is carried away by that enigmatic wink that is an invitation to play and hide, to dive into a fairytale atmosphere that is however only apparent. The beginnings in the mid-10s, in his native Germany, see him – after attending the drama in costume – atypical exponent of expressionist cinema, as his films develop on the blatant exhibition of artifice, on the encounter / clash between public and show, on the sharp irony with which it reveals the separation between illusion and reality. A much less dramatic expressionism than the cut of Fritz Lang, Karl Grune or Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. Despite this, his cinema is not made for escapism: Lubitsch is an avant-garde director, he moves between costumed operetta and sophisticated comedy, he reinterprets Shakespeare (Die Austernprinzessin1919) and attends Expressionist cinema (Die Puppe1919), but he does so keeping his gaze always focused on human reality, stigmatizing the pettiness of greed, reflecting on the complexity and paradoxes of sentimental relationships, and moreover the controversial Weimar Republic offers him subject for investigation, as does the offers to the painters of the Neue Sachlichkeit. Among her female interpreters of her, she knew how to enhance the talent and beauty of Apolonia Chałupiec (better known as Pola Negri), who directed in seven films, including drama, operetta and antimilitarist satire.

LUBITSCH: THE LIGHTS OF HOLLYWOOD

In 1923 he left Europe for the United States, which he amazed with the famous “Lubitsch touch”: it consisted of a particular narrative technique translated into images that did not show all the details of the plot, but left the viewer the task of completing it, imagining the missing scenes or details. This is why his films abound with voices and noises coming from other rooms, with closed doors, with dialogues full of implications. An intuition that, if in Europe it had the merit of making its films captivating, in the United States it proved to be invaluable in avoiding the sharp censorship of that puritanical society. But, paradoxically, precisely the unspoken and the simple allusion were able to suggest much better than words and images what should be kept silent, thanks precisely to Lubitsch’s directorial talent. The allusions of which are not necessarily (indeed almost never) aimed at sex, even if this appears in the form of very refined and sometimes tragic eroticism: as a good observer, but above all as an intellectual who reflects on reality, Lubitsch addresses vibrant criticisms of American conformism, inner discomfort of married life, puritan hypocrisy. And if the American public asked for nothing better than to be able to admire that legendary, libertine, decadent and literary Europe (or what remained of it after the end of Belle Époque), Lubitsch created the atmosphere, but lent it to American situations. An investigation that, in the same years, he was also carrying out Francis Scott Fitzgerald (who had taken the opposite direction, emigrating for a while to Europe), and who will see in his comedy The Vegetable the closest contact between the two authors. However, Lubitsch will always choose to remain in the realm of sophisticated comedy (among the most agreeable examples of a Fitzgeraldian atmosphere, Trouble in Paradise), through which he demonstrated his talent, rising many notches above other European directors who in the meantime had moved to Hollywood. This welcomed him with enthusiasm, but it was Lubitsch who set the rules. To the point of making a satire of anticommunism by directing Greta Garbo in Ninotchka.

LUBITSCH: THE 1940s

The following decade marked the maturity of the director, who signed important films such as Write me stationary mail, Cluny Brown And The shop around the corner, intelligent comedies with a keen eye on the psychological aspects of romantic relationships, tinged with a skilful mixture of romanticism and irony. Because life is not to be taken too seriously. In 1942, now in the middle of the war, Lubitsch turned To be or not to be, a strong satire against Hitler’s madness, in the wake of the Great Chaplinian Dictator (released just two years earlier). The film is still a tribute to Shakespeare and theater, which has been an almost constant reference in his career, featuring his refined style and the way he directed his actors. It was also the last interpretation of Carole Lombard, who would die shortly after in a plane crash. In these last years of activity Lubitsch refined that brilliant irony, but subtly cynical and bitter, and that light fairytale atmosphere that permeates all of his films and which together would also be partly found in the work of Woody Allen. Lubitsch died prematurely on November 30, 1947, due to a heart attack. And he who knows how he would have described the hypocritical America of McCarthyism and the Kennedy Administration.

–Niccolò Lucarelli

The story of Ernst Lubitsch, director and actor 130 years after his birth