The idea of the provincial government to revive the project of the Music Port but in a different place than originally thought -in the municipality of Grenadier Baigorriaglued to rosary beadsand with public-private articulation–, excited important political actors and businessmen. But it generated a strong rejection in the local architectural universe and also among those who were the collaborators of the author of the design, the Brazilian Oscar Niemeyer, and who today are in charge of his studio.

“They didn’t consult us at all; we found out from you about the possibility of changing the location. The project was made for a place and it should be done in that place”said to Rosario3from Rio de Janeiro, Jair Valerawho as technical manager of the construction works Niemeyer – a task that he continues to carry out in the study that he headed until his death, in 2012, the creator of Brasilia – was in Rosario in 2009 and 2010 to supervise the tasks that finally could never start because the administration of Cristina Kirchner never unlocked the transfer to the south of the port activities that were carried out in the chosen property: three hectares located on the coast between Pellegrini and Cerrito.

In the same sense, those who worked on the subject at the local level express themselves: the group of architects that made up the Special Projects Unit of the provincial Ministry of Public Works, which was in charge of Silvana Codinawho was also a couple Hermes Binner and that he accompanied the former governor in the “seduction operation” to convince Niemeyer to carry out the project.

objections

Before the former Minister of Culture Chiqui González, Councilor Verónica Irizar and the College of Architects expressed their opposition to the idea of relocating the Puerto de la Música in the area of the head of the Rosario-Victoria Bridge but on the side of Baigorria, Codina wrote a text that circulated among his colleagues and leaders of socialism with arguments that explain the location chosen in 2008 and question the eventual transfer.

There the Puerto de la Música is described as “a unit with the context, the city of Rosario, and a unit made up of two spheres that are internally assembled at the level of the Paraná River without ravines: there where the plain merges with the water, without further ado”.

For her, as for the College of Architects, carrying out this project -and in fact any other From author– out of the place for which it was intended denatures it. More so in this case, where the land has very different characteristics. For example: one, the one in Rosario, is flush with the water, the other, the one in Baigorria, has a pronounced ravine that would distance the building from the water. “More than 10 meters away from the water in height, over a ravine, the assembly between matter and form would be lost, its interiority would be lost and in this way its spirituality would also be affected,” the letter states.

But in addition, the urban contexts are also different: the Puerto de la Música was conceived as the end of an entire coastal promenade that the city recovered in a process that lasted decades and that required, as stated in this case, the transfer of the port activities that were carried out from Puerto Norte to the south. In that logic, Niemeyer complemented it with another of his projects that came to nothing: the Lucio Fontana Arts Walka walkway with replicas of the great Rosario artist that will connect the Puerto de la Música with the Humberto de Nito Amphitheater and the Monument to the Flag, with an obligatory stop at El Sembrador, the great work of Fontana located in the ravine of Urquiza Park on Avenida Belgrano.

The work “El Sembrador”, by Lucio Fontana and Osvaldo Raúl Palacios.

Another issue pointed out by Codina, who in 2008 carried out the executive project based on Niemeyer’s draft and met with him three times in Brazil to review it, is the link that had been thought between the work, and the cultural activity planned there, with the gastronomic corridor of Pellegrini Avenue.

Although there are other architectural sources consulted by Rosario3 who were more open to the possibility of transferring a work designed for one place to another, in this particular case they raise objections: “There are ethical issues, because here the architect who made the design died and cannot be consulted. So, who is going to be the architect to put the signature for this?”, they say. But they also consider, like Codina, that the issue of heights and the different characteristics of the land is fundamental: “In Baigorria, without that direct dialogue with the river that Niemeyer thought, it will be like a chajá with a strawberry on top.”

Jair Valera It is clear in that sense: “If it were decided in another place, the project must be redefined. There are several components of the work designed according to the site where it was programmed. The opinion of Niemeyer’s team is that it should be done in the original place; we never knew of another place”.

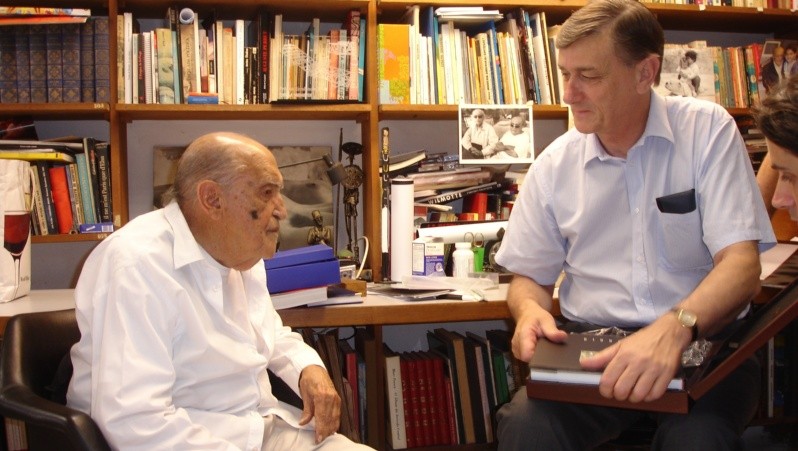

Jair Valera, architect of the Niemeyer studio.

The opportunity

The question is whether, given the difficulties already raised at the time to build the Puerto de la Música on the Belgrano and Pellegrini avenue docks and the lowering of costs that would imply doing it in Baigorria, It is also not worth trying to make the only project of Niemeyer, one of the world’s great masters of modern architecture, come true in Argentina. Something that, based on experiences in other parts of the world, such as the effect of installing a headquarters for the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao, is expected to generate not only cultural benefits but also economic ones for the city and the region.

In this sense, the mayor Paul Javkinwho participated together with his counterpart from Grenadier Baigorria Adrián Maglia in meetings with the governor Omar Perotti in which this topic was analyzed, he said that “it would be important that this work be done, it is a dream of Hermes Binner with which all of us who have government responsibility have to commit ourselves”, and He highlighted the difficulties posed by the original location: the main one is the location of the docks.

“In the former free zone of Bolivia (adjacent to the land that had been thought for the Puerto de la Música) we have cleared the view of the river but we cannot remove the bars and that people pass through there because there were subsidences and fires in that place. ”, he explained. And he estimated that that alone already implies cost overruns of between 40 and 45 million dollars just for the repair of those docks.

“When the project was conceived, the problems of downspouts and dock collapse that we have now did not exist,” he recalled. And although he said he was willing to discuss other possible locations if the province moves towards the completion of the work –something that he still believes is green and therefore the debate is “abstract”– he made it very clear that the location next to the Rosario-Victoria bridge seems more than drinkable. “Parque de la Cabecera is a metropolitan project where this possibility has already been studied. It is not alien to us, it is part of the metropolitan fabric of the city”, he insisted.

In the same sense, the Peronist councilor Norma López, although she was cautious because there was still no official announcement and believes that the general economic context must also be considered, considered that the same difficulties that had already stopped the work, since the land in question still has port activity. Y He believed that if there is an opportunity to do it at the head of the bridge, it should be taken. “For everything that Rosario means, putting it in such a close environment and that values the entire region could go”responded to the query of Rosario3. And he spoke in favor of opening a dialogue with all the sectors that make up culture, the economy and production to analyze it.

On the other side, her socialist colleague Verónica Irizar argued that the Puerto de la Música is “a project of the city”, that it was dreamed of, and that the Nation should take charge of repairing the docks so that it can be carried out in the original location.

Niemeyer with Binner. Silvana Codina was also at that meeting.

Sources who worked on the technical project, meanwhile, clarified that the dock where the work was planned is made of stone, and although it requires adaptation tasks, they had already been foreseen in the tender that was completed at the time to start the jobs (the winning companies could not enter the premises because they were prevented by port workers). Likewise, the arrangement of the docks that Javkin mentioned, those of the former free zone, would be essential so that the surroundings of the Puerto de la Música are also passable and the entire framework planned by Niemeyer is completed, with the Paseo de las Artes Lucio Fontana included.

The plans, the possibilities

Another argument of those who defend the original location is that the project was contemplated in the Rosario Strategic Plan (PER) since 1998. Strictly speaking, in that document what appears is the initiative to build a “Music Stadium”, a space to perform shows of international level, but without defining a location. In 2008, with Niemeyer’s design completed, the Puerto de la Música was included on Belgrano and Pellegrini avenues.

In the PER of 1998, in addition, a possibility is contemplated that is the central axis of the idea that Perotti now proposes for the head of the Rosario-Victoria Bridge: that the financing be carried out through the contribution of private, which -in the governor’s plan- in exchange would obtain public land located in the same area to carry out real estate developments there, in a model that was already applied in the case of the reconversion of Battalion 121. “El Estadio (de la Música) it can be part of a complex that also has other spaces, facilities and services linked to entertainment, recreation and leisure, which can contribute to guaranteeing the profitability of the enterprise. This project could be carried out by the private sector with the support of the local and provincial public sector or by the Municipality with the participation of the private sector”, says the 1998 document.

Of course, the reality today is very different. Because the response that the local administrations gave to that proposal of 24 years ago became a concrete project, the Puerto de la Música. That, as Irizar said, it is a dream that the city took as its own and that was conceived for a certain time and space by two people who are no longer there: Binner and Niemeyer.

So, if it is not done the way it was planned by them, does the possibility of doing the work die along with their mentors? Or should we take the opportunity with the possibilities that arise in this other time and in this new space? Architecture and politics have, at least for now, different answers.

Puerto de la Música: architecture and politics go down different paths