the Revenant

Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu has traveled an exciting path during his career, especially in terms of storytelling. Although he relied heavily on the structure of choral films in his early days, his first three films all exploring several destinies intersecting due to an accident, he was however already trying to vary this narrative model: loves female dogs wanted to be a portrait of Mexico, 21 grams took a more global look at a universal city while babel was taking place in all four corners of the globe.

A variation that continued with Biutiful, his first linear film clinging to a unique point of view, and above all birdman, a feature film structured on a single sequence shot, forcing the filmmaker (and his actors) to completely dismantle the classic narratives to sublimate the content through the form. And Iñárritu went even further. Not with the Revenant – which was certainly a huge technical challenge, but is still based on a very Hollywood narrative structure –, but rather with Carne y Arena.

Looking back before the big leap forward

With his short film in virtual reality (which earned him the very rare honorary Oscar for a special contribution), the Mexican has completely shattered the very idea of cinema and narration. By abandoning the dictatorship of the frame to offer an active viewing experience to spectators, now actors, Carne y Arena revealed an extraordinary immersion where each participant lived a different adventure according to their choices (for the lucky ones who were able to live it, this is unfortunately not the case for the author of these lines).

bardo obviously could not aspire to such an outcome since it is a cinema film, and yet, Iñárritu still transcends its medium. By refusing to constrain oneself to any habitual structure, Iñárritu tries here a much more experimental cinematographic formopening the doors to a cinema of total freedom.

7 ½

As soon as it opens, where a gigantic shadow tries to fly away in the Mexican desert, bardo refers to the introduction of eight and a half by Federico Fellini. This is obviously not trivial since if Fellini followed a depressed filmmaker taking refuge in his memories, the sixth film ofIñárritu tells the story of a character facing an existential crisis plunging him into a true spiritual adventure. And inevitably, like Fellini, Iñárritu will make it an introspection of his own life, using fiction to explore a form of reality.

For the journey of Silverio Gama, Mexican journalist and documentary filmmaker exiled in Los Angeles, returning to his native country to receive a prestigious award, inevitably merges with the journey of Iñárritu himself. The director does not hide it: “Through the cinema, through my alter-ego, Silverio Gama, wonderfully interpreted by Daniel Gimenez CachoI sought to awaken and explore my family memories at the same time as the collective memories of my country”.

Moreover, the many nods to his past filmography (dogs reminiscent of Love female dogs, a man disguised as a rooster evoking birdman, a named store the tower of Babel, this idea of the reviving soul 21 Grams, this mountain of bodies recalling the visions of the hero of the Revenant…) will attest to this throughout the journey.

An exciting choice on paper, which may however be disconcerting. Difficult indeed to fully adhere to the project at first so much the filmmaker decides to shake up the classic codes of narration. Between a baby refusing to be born, a completely flooded subway or a meeting with the United States ambassador where the history of Mexico is replayed under the eyes of Silverio, the first half hour of bardo connects the sequences without ever giving indications to the spectators. Is this the reality of the character or is it pure fantasy? Does he live what the film shows us or does he only imagine it?

Even if the whole is magnificently staged by Iñárritu (the burlesque reconstitution of the impressive battle, the fascinating subjective inaugural flight…), this permanent vagueness leaves you speechless. To the point of asking a major question: is Iñárritu in the middle of a futile ego-trip or is he building, on the contrary, an introspective masterpiece of which we do not have all the keys? Everyone will surely make up their own mind, but it is clear that bardo impregnates the spirit over the sequencesuntil transmitting an unprecedented emotional power.

The emotional click

The emotional click

journey to the end of life

The strength of bardo lies largely in its constant freedom, constantly playing on its mystery to take the spectator where he does not expect it, ever. The trigger also surely comes at the end of this first half hour, when Silverio returns home and indulges in a game of “catch me if you can” with his wife. A game that quickly deviates when she literally disappears in a cupboard before reappearing like a ghost on the edge of a bed, her silhouette merging with the shadows, the rooms transforming as she walks by…

At this moment, bardo completely transformed into a form of surrealism with heartbreaking poetry. An onirism that you should not try to rationalize in each sequence, each discussion… but rather live, simply. Because bardo feels, breathes. If the feature film thus evokes a whole salvo of classic themes – mourning, desire, fear, memory, family, regret, transmission, friendship, parenthood, roots, fame, life of an artist – it is not based on any real narrative marker. On the contrary, it relies almost solely on the strength of pure emotions (despite sometimes obvious symbolism), Iñárritu indulging intimately with poignant humility.

Whether he wonders about the passage of time (this cycle of the sun in a single magical plane), meditates on the history of Mexico (a supernatural exchange with Cortes on a mountain of corpses near the remains of a god), cries a lost child (a moving scene on the beach) or recounts the hell of migrants and/or expatriates (a spectacular border crossing; a customs clearance as comic as it is offensive), bardo sincerity permeates through every plan, every idea. Impossible not to believe for a single second in the authenticity of what the Mexican exhibits during the 2h40 of bardo.

The perpetual chaos of the journey that he offers us is moreover one of the finest proofs of this, Iñárritu never seeking to satisfy the spectator by guiding him, but rather committing himself to making him live this existential journey such as he designed it. Either totally freeing himself from the constraints of time and space, letting his character sail through the places (from a subway to a house, from a Mexico City at night to a sunny beach, from a stroll on the sand to a flight in a plane…) in an intoxicating scenic fluidity and script, accompanied by the bewitching soundtrack by Bryce Dessner (and sometimes Alejandro González Iñárritu himself).

rebirth of an artist

There are inevitably sequences which are more moving than others through this very dense and deceptively light process. Thus, it will probably be easier for a simple European spectator to be moved by all the family passages (without a doubt the most vibrant moments) than by the duty of memory of the History of Mexico. Nevertheless, the journey is so singular that the confusion often prevails over the understanding.

“Life is just a short series of absurd events” moreover strikes Silverio’s father during a terribly touching reunion where the journalist reconnects with his child’s body for the duration of a scene, and this is perhaps what best sums up the scheme of Bard. However, Rarely has a film found so much meaning in its absurdity.

The feature film may well constantly juggle between dream and reality – going from a very concrete talkative sequence (exciting discussion with Luis, probable alter-ego of Guillermo Arriaga, former collaborator of Iñárritu) to a phantasmagorical visual surge (the incredible party scene carried by a let’s dance a capella by David Bowie) with no real binder – the intimate and the universal, the joy and the tragedy, it gains a little more coherence at every moment.

Because even if bardo must be experienced with no other conductive line than that of the heart, Iñárritu doesn’t shirk, offering the key to this mystical ride in the final quarter of the film. The means, at the same time, to reward the persevering spectators and to connect each element with an astounding harmony. Iñárritu then extracts a cathartic work from it, of course, but perhaps also reaches a form of narrative climax, giving birth to its own artistic renaissance. Bright.

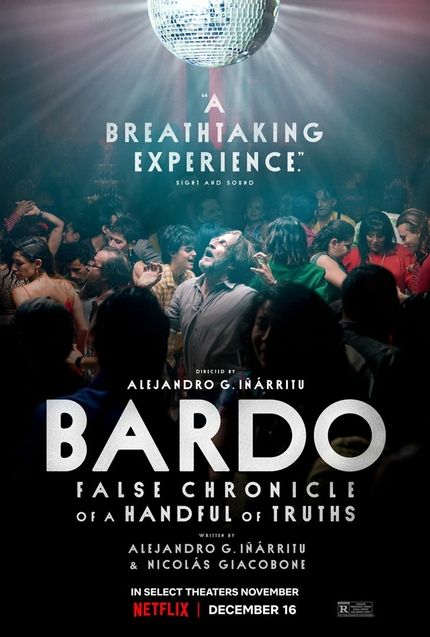

Bardo is available on Netflix since December 16, 2022 in France